The COVID-19 has shut down the world’s economy in short order. While elements of the economy are beginning to open up again, live performances will be one of the last elements to restart. Most club and concert dates have been cancelled for the remainder of the year. For many jazz artists, recorded music is their only source of income. The albums reviewed here are all current releases; most of them were released during the period of nationwide lockdown. Of course, most of the music was recorded long before anyone had heard of the coronavirus. Many of these musicians are still producing music online, which is understandably different than these albums. However, these recordings show us what we as audience members took for granted before the virus. These reviews will be a continuing feature on Jazz History Online as long as the crisis continues. The current set encompasses instrumental and vocal jazz. JHO has always encouraged its readers to support the musicians by purchasing their CDs. The message could not be more urgent now. If you can afford to help, please do.

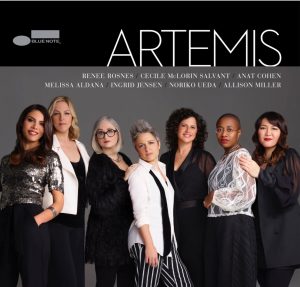

“ARTEMIS” (Blue Note 321590)

One of the most frequent complaints about “supergroups” is that they rarely function as ensembles, focusing on long solos instead of intricate arrangements. Artemis, the new all-star (and all-female) group organized by pianist Renee Rosnes, is an exception to the rule. Their new eponymous album has been eagerly awaited since the group’s outstanding performance at the 2018 Newport Jazz Festival. The opening track, drummer Allison Miller’s “Goddess of the Hunt” reminds me of Maria Schneider’s big band charts with its ebbing and flowing phrases, and the delicate counterpoint between the horns. Trumpeter Ingrid Jensen, tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana, clarinetist Anat Cohen and Rosnes all play short and efficient solos on this track, but the spotlight remains on the ensemble with its myriad range of instrumental colors. To be sure, there are plenty of solo opportunities on the album, as on the second track, which features a glorious extended solo by Aldana on her composition, “Frida”. In an interview, Jensen said that her arrangement of “Fool on the Hill” was inspired the current political turmoil. Regardless of its origins, the setting is extraordinary, with great variations on the theme occurring through the chart, appearing alongside and between the searing solos by Jensen, Rosnes, and Miller. Miller’s resourceful and flexible percussion drives Rosnes’ original “Big Top”, and the drum solo—performed over a vamp and horn interjections—is a remarkable display of technique and musicianship. Following Miller, the style jumps into a powerful up-tempo swing for brilliant solos by Rosnes and Aldana, then twists back to the polyrhythmic opening for an intense melodic variation by the horns. The seventh member of Artemis is vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant, and she is featured on two tracks, both arranged by Rosnes. On Stevie Wonder’s “If It’s Magic”, the background is in an open rubato style, which allows the sound to expand and contract with Salvant’s phrases. “Cry Buttercup Cry” is a throwback to the swing style, with Salvant floating over a smooth 4/4 rhythm and sustained chords. Cohen’s fluid clarinet, Jensen’s harmon-muted trumpet and Aldana’s smoky tenor add just the right flair. “Notturno” is a moody Cohen original co-arranged by Cohen and Rosnes, featuring a gorgeous melody voiced in thirds for clarinet and trumpet, and a haunting bass vamp performed by Noriko Ueda. The improvisation segues in and out of solo and dialogue episodes between the clarinet and bass. Ueda’s sole original is a sunny jazz waltz called “Step Forward”, and the interplay between Cohen and the rhythm section is exhilarating. Jensen’s understated solo leads into Ueda’s rich-toned and melodic improvisation, and Rosnes closes out the solos with a brilliant statement which continues under the final chorus. The album closes with a slow, sexy arrangement of Lee Morgan’s “Sidewinder”. Instead of full solos, the horns (including Cohen’s juicy bass clarinet) exchange thoughts of varying lengths over the blues changes. Then, to maintain the same texture, Rosnes’ solo is accompanied with an ensemble variation. This flawless album lives up to all of the hype and expectations. It is certainly one of the outstanding releases of 2020.

One of the most frequent complaints about “supergroups” is that they rarely function as ensembles, focusing on long solos instead of intricate arrangements. Artemis, the new all-star (and all-female) group organized by pianist Renee Rosnes, is an exception to the rule. Their new eponymous album has been eagerly awaited since the group’s outstanding performance at the 2018 Newport Jazz Festival. The opening track, drummer Allison Miller’s “Goddess of the Hunt” reminds me of Maria Schneider’s big band charts with its ebbing and flowing phrases, and the delicate counterpoint between the horns. Trumpeter Ingrid Jensen, tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana, clarinetist Anat Cohen and Rosnes all play short and efficient solos on this track, but the spotlight remains on the ensemble with its myriad range of instrumental colors. To be sure, there are plenty of solo opportunities on the album, as on the second track, which features a glorious extended solo by Aldana on her composition, “Frida”. In an interview, Jensen said that her arrangement of “Fool on the Hill” was inspired the current political turmoil. Regardless of its origins, the setting is extraordinary, with great variations on the theme occurring through the chart, appearing alongside and between the searing solos by Jensen, Rosnes, and Miller. Miller’s resourceful and flexible percussion drives Rosnes’ original “Big Top”, and the drum solo—performed over a vamp and horn interjections—is a remarkable display of technique and musicianship. Following Miller, the style jumps into a powerful up-tempo swing for brilliant solos by Rosnes and Aldana, then twists back to the polyrhythmic opening for an intense melodic variation by the horns. The seventh member of Artemis is vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant, and she is featured on two tracks, both arranged by Rosnes. On Stevie Wonder’s “If It’s Magic”, the background is in an open rubato style, which allows the sound to expand and contract with Salvant’s phrases. “Cry Buttercup Cry” is a throwback to the swing style, with Salvant floating over a smooth 4/4 rhythm and sustained chords. Cohen’s fluid clarinet, Jensen’s harmon-muted trumpet and Aldana’s smoky tenor add just the right flair. “Notturno” is a moody Cohen original co-arranged by Cohen and Rosnes, featuring a gorgeous melody voiced in thirds for clarinet and trumpet, and a haunting bass vamp performed by Noriko Ueda. The improvisation segues in and out of solo and dialogue episodes between the clarinet and bass. Ueda’s sole original is a sunny jazz waltz called “Step Forward”, and the interplay between Cohen and the rhythm section is exhilarating. Jensen’s understated solo leads into Ueda’s rich-toned and melodic improvisation, and Rosnes closes out the solos with a brilliant statement which continues under the final chorus. The album closes with a slow, sexy arrangement of Lee Morgan’s “Sidewinder”. Instead of full solos, the horns (including Cohen’s juicy bass clarinet) exchange thoughts of varying lengths over the blues changes. Then, to maintain the same texture, Rosnes’ solo is accompanied with an ensemble variation. This flawless album lives up to all of the hype and expectations. It is certainly one of the outstanding releases of 2020.

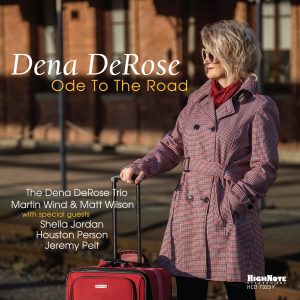

DENA DE ROSE: “ODE TO THE ROAD” (High Note 7323)

When Dena DeRose recorded her latest album, “Ode to the Road” in October  2019, no one had yet heard of the COVID-19 virus, and certainly we couldn’t predict that musicians would be absent from the road throughout most of 2020 (and probably into 2021). Thus, the title song—co-composed by Alan Broadbent and Mark Murphy—sounds a little more wistful to those listening to it while in semi-lockdown. Yet, I wonder how many musicians are itching to get back to the long drives, bad hotels, junk food and all of the other hassles of touring. DeRose’s vocal mixes the sardonic lyrics with a sunny delivery, as if to say performing concerts is tough, but it yields plenty of rewards. In addition to saluting the traveling musician, DeRose also pays tribute to three great jazz vocalists, Mark Murphy, Bob Dorough and Sheila Jordan. Jordan was the only one of the three still alive to record on the album, and her brilliant reading of “Little Willie Leaps” shows that she remains a vital presence on the jazz scene, even as she approaches her 92nd birthday. DeRose’s simultaneous vocal on “All God’s Children Got Rhythm” is an interesting touch, but Jordan’s ensuing chorus where she tells of the origins of the lyric are a welcome piece of oral history. The scat exchanges between the two vocalists are a fun addition to the track. Before Jordan makes her first guest appearance, DeRose and her wonderful trio (Martin Wind, bass; Matt Wilson, drums) perform a sprightly rendition of Dorough’s “Nothing Like You” followed by another Murphy/Broadbent collaboration, “Don’t Ask Why”. The latter piece carries one of Murphy’s most philosophical lyrics, and as on earlier albums, DeRose rescues an inexplicably obscure song through a sensitive reading and impeccable arrangement. DeRose’s trio has been together for over two decades, and even though they don’t play together as much as they’d like, they seem to be a better ensemble every time they reunite. Each member knows how to use space so that each voice can be heard at any given time. DeRose has a spare approach to comping, which makes room for Wind’s meaty tone and Wilson’s crackling responses. Wind’s arco bass solo is a perfect complement to the soulful Jordan/DeRose duet on Dorough’s “Small Day Tomorrow”. Houston Person—another rescuer of forgotten songs—adds his burnished tenor to a passionate version of “The Way We Were”, and Jeremy Pelt plays a sassy Lee Morgan-inspired trumpet solo on “Cross Me Off Your List”. The band picks up on Pelt’s influence and before long, they have a real “Blues March” groove happening, with DeRose playing thick Bobby Timmons chords and Wilson providing a pared-down homage to Art Blakey. The impeccable ballad “I Have the Feeling I’ve Been Here Before” precedes “A Tip of the Hat”, a bop original which includes a piano solo that bubbles over with ideas, an exuberant bass solo, and drum exchanges with judicious use of the cymbals. Person returns for the closer, a medium-tempo workout on “The Days of Wine and Roses”. DeRose has performed on a few livestream concerts during the lockdown, but I look forward to the day when she gets back on the road.

2019, no one had yet heard of the COVID-19 virus, and certainly we couldn’t predict that musicians would be absent from the road throughout most of 2020 (and probably into 2021). Thus, the title song—co-composed by Alan Broadbent and Mark Murphy—sounds a little more wistful to those listening to it while in semi-lockdown. Yet, I wonder how many musicians are itching to get back to the long drives, bad hotels, junk food and all of the other hassles of touring. DeRose’s vocal mixes the sardonic lyrics with a sunny delivery, as if to say performing concerts is tough, but it yields plenty of rewards. In addition to saluting the traveling musician, DeRose also pays tribute to three great jazz vocalists, Mark Murphy, Bob Dorough and Sheila Jordan. Jordan was the only one of the three still alive to record on the album, and her brilliant reading of “Little Willie Leaps” shows that she remains a vital presence on the jazz scene, even as she approaches her 92nd birthday. DeRose’s simultaneous vocal on “All God’s Children Got Rhythm” is an interesting touch, but Jordan’s ensuing chorus where she tells of the origins of the lyric are a welcome piece of oral history. The scat exchanges between the two vocalists are a fun addition to the track. Before Jordan makes her first guest appearance, DeRose and her wonderful trio (Martin Wind, bass; Matt Wilson, drums) perform a sprightly rendition of Dorough’s “Nothing Like You” followed by another Murphy/Broadbent collaboration, “Don’t Ask Why”. The latter piece carries one of Murphy’s most philosophical lyrics, and as on earlier albums, DeRose rescues an inexplicably obscure song through a sensitive reading and impeccable arrangement. DeRose’s trio has been together for over two decades, and even though they don’t play together as much as they’d like, they seem to be a better ensemble every time they reunite. Each member knows how to use space so that each voice can be heard at any given time. DeRose has a spare approach to comping, which makes room for Wind’s meaty tone and Wilson’s crackling responses. Wind’s arco bass solo is a perfect complement to the soulful Jordan/DeRose duet on Dorough’s “Small Day Tomorrow”. Houston Person—another rescuer of forgotten songs—adds his burnished tenor to a passionate version of “The Way We Were”, and Jeremy Pelt plays a sassy Lee Morgan-inspired trumpet solo on “Cross Me Off Your List”. The band picks up on Pelt’s influence and before long, they have a real “Blues March” groove happening, with DeRose playing thick Bobby Timmons chords and Wilson providing a pared-down homage to Art Blakey. The impeccable ballad “I Have the Feeling I’ve Been Here Before” precedes “A Tip of the Hat”, a bop original which includes a piano solo that bubbles over with ideas, an exuberant bass solo, and drum exchanges with judicious use of the cymbals. Person returns for the closer, a medium-tempo workout on “The Days of Wine and Roses”. DeRose has performed on a few livestream concerts during the lockdown, but I look forward to the day when she gets back on the road.

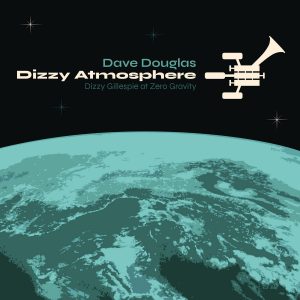

DAVE DOUGLAS: “DIZZY ATMOSPHERE” (Greenleaf 1076)

The full title of Dave Douglas’ new album is “Dizzy Atmosphere: Dizzy Gillespie in Zero Gravity”. Douglas, rightly believes that he can pay tribute to jazz icons without playing multiple selections from their songbook. Douglas has only included only two Gillespie tunes in this set, but summons his spirit in the remaining originals. To be certain, this is not a bebop album, but elements of Dizzy are stamped all over it. You might not catch the quote from “Bebop” in the opening tune “Mondrian”, but Douglas’ fiery trumpet solo is clearly inspired by Gillespie. The next two compositions “Con Almazan” and “Cadillac” contain distinctive similarities to “Con Alma” and “Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac”, the former with its loping rhythm (much like the 1957 recording with Sonny Stitt) and the latter through melodic paraphrase. Douglas’ band utilizes his own trumpet along with a younger colleague, trumpeter Dave Adewumi, and while the two don’t lock axes like Gillespie and Jon Faddis, they feed off each other’s ideas and momentum. Matt Stevens is a much more futuristic guitarist than anyone Gillespie hired, but Douglas’ arrangements make him fit in with the progressive—but tradition-centered—rhythm section of Fabian Almazan (piano), Carmen Rothwell (bass) and Joey Baron (drums). The moody ballad “See Me Now” (which sounds nothing like Tadd Dameron) precedes two Gillespie classics, “Manteca” and “Pickin’ the Cabbage”. Interestingly, the main theme of “Manteca” as played here is the Chano Pozo section of the tune (Dizzy wrote the bridge), but when the band moves into a fragmented swing, Stevens drops Dizzy’s melody in its proper place. The trumpet chase is a thriller with more Gillespiean leaps than anywhere else on the album. The rhythm section is in especially fine form, changing (and sometimes morphing) styles with skill and elegance. “Pickin’ the Cabbage” was a tune Gillespie wrote when he was featured trumpeter in the Cab Calloway band. Douglas’ arrangement transforms the piece with effective stop-time episodes built into the chart and single-chord episodes that yield several trumpet growls. However, despite the overall changes, Douglas keeps both the original tune and the out-chorus variation intact. “Pacific” is a stunning free-styled ballad filled with active interplay across the band. Its exact relevance to Gillespie is unclear to me, except that there is a great feeling of adventure as the band navigates this unusual composition. “Subterfuge” conveys both traditional bebop and the freer conception of Ornette Coleman (think “Congeniality”). The tune alternates between the two concepts as swing yields to broken time, and vice versa. I doubt that there are many musicians who could maneuver this complex tune without spending a lot of time with it in the woodshed! “We Pray” closes the album on a peaceful note with a firmly grounded bass line from Rothwell and sensitive solos by the rest of the band. I suspect that Dizzy would have enjoyed this music very much.

The full title of Dave Douglas’ new album is “Dizzy Atmosphere: Dizzy Gillespie in Zero Gravity”. Douglas, rightly believes that he can pay tribute to jazz icons without playing multiple selections from their songbook. Douglas has only included only two Gillespie tunes in this set, but summons his spirit in the remaining originals. To be certain, this is not a bebop album, but elements of Dizzy are stamped all over it. You might not catch the quote from “Bebop” in the opening tune “Mondrian”, but Douglas’ fiery trumpet solo is clearly inspired by Gillespie. The next two compositions “Con Almazan” and “Cadillac” contain distinctive similarities to “Con Alma” and “Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac”, the former with its loping rhythm (much like the 1957 recording with Sonny Stitt) and the latter through melodic paraphrase. Douglas’ band utilizes his own trumpet along with a younger colleague, trumpeter Dave Adewumi, and while the two don’t lock axes like Gillespie and Jon Faddis, they feed off each other’s ideas and momentum. Matt Stevens is a much more futuristic guitarist than anyone Gillespie hired, but Douglas’ arrangements make him fit in with the progressive—but tradition-centered—rhythm section of Fabian Almazan (piano), Carmen Rothwell (bass) and Joey Baron (drums). The moody ballad “See Me Now” (which sounds nothing like Tadd Dameron) precedes two Gillespie classics, “Manteca” and “Pickin’ the Cabbage”. Interestingly, the main theme of “Manteca” as played here is the Chano Pozo section of the tune (Dizzy wrote the bridge), but when the band moves into a fragmented swing, Stevens drops Dizzy’s melody in its proper place. The trumpet chase is a thriller with more Gillespiean leaps than anywhere else on the album. The rhythm section is in especially fine form, changing (and sometimes morphing) styles with skill and elegance. “Pickin’ the Cabbage” was a tune Gillespie wrote when he was featured trumpeter in the Cab Calloway band. Douglas’ arrangement transforms the piece with effective stop-time episodes built into the chart and single-chord episodes that yield several trumpet growls. However, despite the overall changes, Douglas keeps both the original tune and the out-chorus variation intact. “Pacific” is a stunning free-styled ballad filled with active interplay across the band. Its exact relevance to Gillespie is unclear to me, except that there is a great feeling of adventure as the band navigates this unusual composition. “Subterfuge” conveys both traditional bebop and the freer conception of Ornette Coleman (think “Congeniality”). The tune alternates between the two concepts as swing yields to broken time, and vice versa. I doubt that there are many musicians who could maneuver this complex tune without spending a lot of time with it in the woodshed! “We Pray” closes the album on a peaceful note with a firmly grounded bass line from Rothwell and sensitive solos by the rest of the band. I suspect that Dizzy would have enjoyed this music very much.

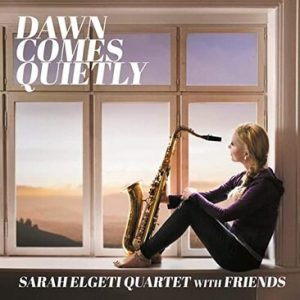

SARAH ELGETI: “DAWN COMES QUIETLY” (self-released)

Within the first 45 seconds of Sarah Elgeti’s new album, “Dawn Comes Quietly”, we get an overview of some of the sounds to come over the next  hour. Elgeti’s bass clarinet opens a classical trio with flute (also Elgeti, through overdubbing) and clarinet (Soren Birkelund). Then Elgeti’s bass clarinet initiates a vamp, which brings in the rhythm section. Elgeti’s original melody “Magical Thinking” is effortlessly passed among the horns before yielding to a lyric bass solo (Anders Krogh Fjeldsted) and reflective piano (Nils Raae). While the gentle timbres of “Magical Thinking” might have been enough to carry an entire album, Elgeti has more colors to show, as on the next track, “Whereto?” where she sets the vocals of Sidsel Storm in front of the woodwinds and rhythm. Elgeti takes her first solo here, and she displays a singing flute tone and deep melodic sensibilities as she improvises in the lower range of the instrument. “Changing Whispers” offers a contrast with Elgeti’s meaty tenor sax paired with Raae’s harmonica over an adapted blues-with-a-bridge form. Raae digs out some analog keyboards for “A Lot of People, A Lot of Sad Stories”, and his solo works idiomatically over the samba beat laid down by Henrik Holst Hansen. The overtones from Elgeti’s tenor stand out over the muddy sound of the synths. The woodwinds return for “Autumn”, another Elgeti original featuring Storm. The ensuing flute and piano solos are quite elegant, and Storm displays superb English diction on both features. The all-too-brief “Crazy Destiny” spotlights the harmonica/tenor front line, with a resourceful drum solo added for good measure. The tender ballad “Introspection” (not the Monk tune) couples Elgeti’s flute with Marianne Cæcilia Eriksen’s baritone sax. It shouldn’t be any surprise for a baritone saxophonist to show a Gerry Mulligan influence, but I like that she draws from Mulligan’s later period, when he displayed a lighter touch to the big horn. “Gather Courage” finds Elgeti’s tenor with only bass and drums. It’s not as adventurous as I had hoped, but the interplay between the instruments is quite spirited. The meditative “Snow” is the final Elgeti original on the album, and it is followed by two pieces by Carl Nielsen, both arranged by Elgeti (the first “En Sommeraften” features another fine soloist—virtually inaudible in his other appearance—violinist Alexander Kraglund). As you might have guessed from the names, Elgeti and all of the other musicians are Danish. The Danish people value a particular state of being called “hygge”, which translates to a feeling of comfort and well-being. There’s a lot of hygge on this lovely album.

hour. Elgeti’s bass clarinet opens a classical trio with flute (also Elgeti, through overdubbing) and clarinet (Soren Birkelund). Then Elgeti’s bass clarinet initiates a vamp, which brings in the rhythm section. Elgeti’s original melody “Magical Thinking” is effortlessly passed among the horns before yielding to a lyric bass solo (Anders Krogh Fjeldsted) and reflective piano (Nils Raae). While the gentle timbres of “Magical Thinking” might have been enough to carry an entire album, Elgeti has more colors to show, as on the next track, “Whereto?” where she sets the vocals of Sidsel Storm in front of the woodwinds and rhythm. Elgeti takes her first solo here, and she displays a singing flute tone and deep melodic sensibilities as she improvises in the lower range of the instrument. “Changing Whispers” offers a contrast with Elgeti’s meaty tenor sax paired with Raae’s harmonica over an adapted blues-with-a-bridge form. Raae digs out some analog keyboards for “A Lot of People, A Lot of Sad Stories”, and his solo works idiomatically over the samba beat laid down by Henrik Holst Hansen. The overtones from Elgeti’s tenor stand out over the muddy sound of the synths. The woodwinds return for “Autumn”, another Elgeti original featuring Storm. The ensuing flute and piano solos are quite elegant, and Storm displays superb English diction on both features. The all-too-brief “Crazy Destiny” spotlights the harmonica/tenor front line, with a resourceful drum solo added for good measure. The tender ballad “Introspection” (not the Monk tune) couples Elgeti’s flute with Marianne Cæcilia Eriksen’s baritone sax. It shouldn’t be any surprise for a baritone saxophonist to show a Gerry Mulligan influence, but I like that she draws from Mulligan’s later period, when he displayed a lighter touch to the big horn. “Gather Courage” finds Elgeti’s tenor with only bass and drums. It’s not as adventurous as I had hoped, but the interplay between the instruments is quite spirited. The meditative “Snow” is the final Elgeti original on the album, and it is followed by two pieces by Carl Nielsen, both arranged by Elgeti (the first “En Sommeraften” features another fine soloist—virtually inaudible in his other appearance—violinist Alexander Kraglund). As you might have guessed from the names, Elgeti and all of the other musicians are Danish. The Danish people value a particular state of being called “hygge”, which translates to a feeling of comfort and well-being. There’s a lot of hygge on this lovely album.

BRIAN LANDRUS: “FOR NOW” (BlueLand 2020)

“For Now”, the latest recording from low reed specialist Brian Landrus,  demonstrates his abundant depth as both composer and performer. “The Signs” opens the album with a strong Blue Note groove. Sidemen Michael Rodriguez (trumpet), Fred Hersch (piano), Drew Gress (bass) and Billy Hart (drums) all know this music well, and each fills their prescribed roles. But Landrus takes a different approach, inserting less notes and more passion into his solo. It’s an interesting gambit, and it succeeds because of the raw emotion that flows through his baritone sax. The next track is a ballad, “Clarity in Time” where Landrus and the rhythm section are joined by a string quartet [Sara Caswell, Joyce Hammann (violins); Lois Martin (viola); Jody Redhage-Ferber (cello)]. The high, icy texture of the strings (arranged by Landrus and Robert Livingston Aldridge) create a unique background for Landrus’ baritone sax, which sings with great tenderness. Hersch also adapts a softer touch than before, making his entrances notable but not obtrusive. “The Miss” is a jazz waltz which combines the disparate elements of the previous two tracks: a finely-written melody for the horns, an integral role for the strings, and a gentle mood that floats over the rhythm. “JJ” brings back the Blue Note feel, but the composition style is much more progressive. The rhythm shifts around in unexpected ways (Hart’s multi-faceted drumming is breathtaking), the chords for the solo section are much more open than the tune suggests, and Landrus, Rodriguez and Hersch find strikingly different ways to express themselves within the structure. Landrus switches to bass clarinet for the title composition, a cameo, lasting under three minutes and sounding thorough-composed. Landrus finds plenty of room for interpretation as he intones the haunting melody. Landrus’ unaccompanied bass clarinet turn on “Round Midnight” owes a lot to Eric Dolphy’s classic solo on “God Bless the Child”. The same approach to arpeggiated chords mixed with melody appears here. Unlike Dolphy, Landrus keeps this feature short, abruptly ending after just one chorus (and before resolving the final harmony). Brunislaw Kaper’s “Invitation” starts as a slow rubato ballad with the strings, but Hart’s drums soon signal a shift to a much faster tempo. Landrus builds up the heat as he navigates this fiendishly difficult tune before yielding to Hersch’s nimble fingers. “For Whom I Imagined” sounds like a companion piece to the title track, but Landrus differentiates the two pieces by overdubbing a flute improvisation over the melody. He moves to alto flute for “The Night of Change”, another piece in 3/4 time (Review the track sequence and you’ll discover a loosely palindromic approach to the playlist). The scoring for “The Second Time” doubles Landrus’ bari with the cello, separating the rest of the string quartet for illuminating counterpoint. “Her Smile” leads off with exuberant collective improvisation from the horns before the strings take the melody (with the lower strings taking a different direction). Landrus and the strings are at nearly equal dynamics during the baritone solo encouraging interaction between the two forces. Then Caswell emerges from the quartet for a superb improvisation, and immediately drops back to the quartet for an intricate variation chorus. The rhythm section gets the spotlight on Landrus’ final original “The Wait”. Hersch handles the melodic statement, and after a brief bari solo, Hersch and Gress stretch out for extended statements. Landrus moves back to bass clarinet for a longer solo and the recap of the melody. This wonderful album closes with an intimate duet on “Ruby, My Dear”, as Landrus and Hersch display their mastery of playing ballads. Actually, an all-ballads duo album might be a splendid follow-up…

demonstrates his abundant depth as both composer and performer. “The Signs” opens the album with a strong Blue Note groove. Sidemen Michael Rodriguez (trumpet), Fred Hersch (piano), Drew Gress (bass) and Billy Hart (drums) all know this music well, and each fills their prescribed roles. But Landrus takes a different approach, inserting less notes and more passion into his solo. It’s an interesting gambit, and it succeeds because of the raw emotion that flows through his baritone sax. The next track is a ballad, “Clarity in Time” where Landrus and the rhythm section are joined by a string quartet [Sara Caswell, Joyce Hammann (violins); Lois Martin (viola); Jody Redhage-Ferber (cello)]. The high, icy texture of the strings (arranged by Landrus and Robert Livingston Aldridge) create a unique background for Landrus’ baritone sax, which sings with great tenderness. Hersch also adapts a softer touch than before, making his entrances notable but not obtrusive. “The Miss” is a jazz waltz which combines the disparate elements of the previous two tracks: a finely-written melody for the horns, an integral role for the strings, and a gentle mood that floats over the rhythm. “JJ” brings back the Blue Note feel, but the composition style is much more progressive. The rhythm shifts around in unexpected ways (Hart’s multi-faceted drumming is breathtaking), the chords for the solo section are much more open than the tune suggests, and Landrus, Rodriguez and Hersch find strikingly different ways to express themselves within the structure. Landrus switches to bass clarinet for the title composition, a cameo, lasting under three minutes and sounding thorough-composed. Landrus finds plenty of room for interpretation as he intones the haunting melody. Landrus’ unaccompanied bass clarinet turn on “Round Midnight” owes a lot to Eric Dolphy’s classic solo on “God Bless the Child”. The same approach to arpeggiated chords mixed with melody appears here. Unlike Dolphy, Landrus keeps this feature short, abruptly ending after just one chorus (and before resolving the final harmony). Brunislaw Kaper’s “Invitation” starts as a slow rubato ballad with the strings, but Hart’s drums soon signal a shift to a much faster tempo. Landrus builds up the heat as he navigates this fiendishly difficult tune before yielding to Hersch’s nimble fingers. “For Whom I Imagined” sounds like a companion piece to the title track, but Landrus differentiates the two pieces by overdubbing a flute improvisation over the melody. He moves to alto flute for “The Night of Change”, another piece in 3/4 time (Review the track sequence and you’ll discover a loosely palindromic approach to the playlist). The scoring for “The Second Time” doubles Landrus’ bari with the cello, separating the rest of the string quartet for illuminating counterpoint. “Her Smile” leads off with exuberant collective improvisation from the horns before the strings take the melody (with the lower strings taking a different direction). Landrus and the strings are at nearly equal dynamics during the baritone solo encouraging interaction between the two forces. Then Caswell emerges from the quartet for a superb improvisation, and immediately drops back to the quartet for an intricate variation chorus. The rhythm section gets the spotlight on Landrus’ final original “The Wait”. Hersch handles the melodic statement, and after a brief bari solo, Hersch and Gress stretch out for extended statements. Landrus moves back to bass clarinet for a longer solo and the recap of the melody. This wonderful album closes with an intimate duet on “Ruby, My Dear”, as Landrus and Hersch display their mastery of playing ballads. Actually, an all-ballads duo album might be a splendid follow-up…

ALLEGRA LEVY: “LOSE MY NUMBER” (SteepleChase 31900)

I wish I had one-tenth of the political power of the COVID-19 virus. Has any  other event—including the current political shenanigans—ever changed lives so completely in such a short time? Vocalist Allegra Levy acknowledges that her lyrics to “Samba de Beach”—the opening track on her new disc “Lose My Number”—were inspired by the virus, specifically the doubts and fears she’s experienced since the lockdown. Levy sings In another life, I could’ve been somebody. Someone you might have heard of. Levy is making a name for herself in jazz circles, and this album marks another step in her artistic development. All of the songs on “Lose My Number” feature Levy’s words to the instrumental originals of her teacher and mentor, John McNeil. Levy’s amazing technique allows her to navigate McNeil’s angular lines with ease, and it is clear that Levy and the outstanding ensemble have rehearsed this music to a point of deep familiarity. Levy deliberately assembled an all-female rhythm section for this project, and the empathy displayed by Carmen Staaf (piano), Carmen Rothwell (bass) and Colleen Clark (drums) is a model for any trio. The charming love song “Livin’ Small” is loaded with wonderful moments, including the interplay between the instruments under Levy’s vocals, the fine piano and bass solos, and the precise cymbal touches in the final chorus. The opening of “Tiffany” finds Levy singing in the lowest part of her range. Listen carefully and you can hear Levy stylizing on those low notes, much as the late Jeanne Lee did with Ran Blake a generation ago. The melody remains low in Levy’s voice, which creates a smooth transition to Rothwell’s melodic bass solo. The dynamics are subdued throughout the arrangement, with Staaf’s gentle piano solo and Clark’s understated percussion also contributing to the delicate mood—completely in accord with a song whose title refers to both fine jewelry and a woman. On “Strictly Ballroom”, “C.J.” and “Zephyr”, McNeil adds his burnished trumpet tone to the ensemble. The trumpet and voice make an intriguing front line, with the two principals combining for short riffs, and inspiring each other’s improvisations. Matthew Arnold’s classic poem “Dover Beach” has inspired many artists, including Samuel Barber, John McNeil, and Allegra Levy. Levy’s original words capture the melancholy of the Arnold poem, and pays tribute to her late grandmother. One of the highlights of the album is this track’s gently interweaving dual improvisation between Levy and Staaf. “Ukulele Song” is a charming throwback with Pierre Dorge playing the title instrument. The album ends with the sardonic title tune. Levy’s lyric is a forceful rebuke to a potential lover, and the composition is a virtual landmine with broken time patterns, changing tempos and mixed meters. However, Levy and her trio make it sound like an elaborate game of hopscotch. The artistic success of this album proves that Allegra Levy made the right career choice after all. May her music continue to challenge and delight us for many years to come.

other event—including the current political shenanigans—ever changed lives so completely in such a short time? Vocalist Allegra Levy acknowledges that her lyrics to “Samba de Beach”—the opening track on her new disc “Lose My Number”—were inspired by the virus, specifically the doubts and fears she’s experienced since the lockdown. Levy sings In another life, I could’ve been somebody. Someone you might have heard of. Levy is making a name for herself in jazz circles, and this album marks another step in her artistic development. All of the songs on “Lose My Number” feature Levy’s words to the instrumental originals of her teacher and mentor, John McNeil. Levy’s amazing technique allows her to navigate McNeil’s angular lines with ease, and it is clear that Levy and the outstanding ensemble have rehearsed this music to a point of deep familiarity. Levy deliberately assembled an all-female rhythm section for this project, and the empathy displayed by Carmen Staaf (piano), Carmen Rothwell (bass) and Colleen Clark (drums) is a model for any trio. The charming love song “Livin’ Small” is loaded with wonderful moments, including the interplay between the instruments under Levy’s vocals, the fine piano and bass solos, and the precise cymbal touches in the final chorus. The opening of “Tiffany” finds Levy singing in the lowest part of her range. Listen carefully and you can hear Levy stylizing on those low notes, much as the late Jeanne Lee did with Ran Blake a generation ago. The melody remains low in Levy’s voice, which creates a smooth transition to Rothwell’s melodic bass solo. The dynamics are subdued throughout the arrangement, with Staaf’s gentle piano solo and Clark’s understated percussion also contributing to the delicate mood—completely in accord with a song whose title refers to both fine jewelry and a woman. On “Strictly Ballroom”, “C.J.” and “Zephyr”, McNeil adds his burnished trumpet tone to the ensemble. The trumpet and voice make an intriguing front line, with the two principals combining for short riffs, and inspiring each other’s improvisations. Matthew Arnold’s classic poem “Dover Beach” has inspired many artists, including Samuel Barber, John McNeil, and Allegra Levy. Levy’s original words capture the melancholy of the Arnold poem, and pays tribute to her late grandmother. One of the highlights of the album is this track’s gently interweaving dual improvisation between Levy and Staaf. “Ukulele Song” is a charming throwback with Pierre Dorge playing the title instrument. The album ends with the sardonic title tune. Levy’s lyric is a forceful rebuke to a potential lover, and the composition is a virtual landmine with broken time patterns, changing tempos and mixed meters. However, Levy and her trio make it sound like an elaborate game of hopscotch. The artistic success of this album proves that Allegra Levy made the right career choice after all. May her music continue to challenge and delight us for many years to come.

MARIA SCHNEIDER ORCHESTRA: “DATA LORDS” (ArtistShare 176)

William Shakespeare coined the phrase “brave new world” to denote something bold and dazzling. The current meaning of “brave” refers to courage, and it takes a special kind of courage to battle something as bold and dazzling as the internet. For the past several years, Maria Schneider has waged her own battle with technology giants like Google, Facebook and Spotify. She shares her distrust of these companies with other musicians who are robbed of royalties and other income due to streaming and downloading. However, Schneider has a greater concern with the collection of personal data by these companies, and the possible ramifications to current and future generations. She has given many speeches and written several articles on the evils lurking within cyberspace, but her new double-disc set, “Data Lords” is her musical protest against the tech giants. I heard a couple of these protest works at a Schneider concert in Lakewood two years ago, and since then, I have wondered and worried about the effect this music would have on her career. After listening to both discs of “Data Lords”, I can honestly report that while much of this music is new and quite different, it represents an essential chapter in Schneider’s growth as a composer. Many of the pieces (including half of the compositions on the “pastoral” disc, “Our Natural World”) have no discernable melodies, as Schneider paints vivid pictures of scenes and situations using the short motives and punctuations of absolute music. On these pieces, the thrilling group crescendos that once heaved and sighed as a passionate outgrowth of the music, are at times, terrifying—with soloists like Ryan Keberle (trombone), Rich Perry (tenor sax), Greg Gisbert (trumpet) and Ben Monder (guitar) playing exclamatory statements over Schneider’s dense and powerful orchestrations. Schneider’s much-copied pastel chords have been replaced with new tone combinations, some of which mimic electronic sounds through acoustic instruments. Schneider has not abandoned the big band style—indeed, much of the protest music sounds like an extension of concepts developed by Charlie Haden and Carla Bley for their Liberation Music Orchestra—but she has greatly expanded her tonal palette to create these dramatic works. I won’t offer a track-by-track analysis of this album because this is music that must be experienced for both its visceral and emotional content. I will assure you that the intensity is broken up with humor and passions, and that the set contains generous portions of the lyrical Schneider style (including one piece on the protest “Digital World” disc). The CDs are not marked in sequence (i.e., disc one and disc two) but the elaborate booklet that comes with the set seems to indicate that “Digital World” precedes “Our Natural World”. That’s the order in which I listened to the discs as I prepared this review; the next time I listen, I think that I’ll reverse the discs—it might provide a completely different listening experience. Listen well to this music and heed Schneider’s warnings. They provide a grim reminder that the problems of our world are far greater than the significant issues of COVID-19, racial injustice, and corrupt governments. To complete Shakespeare’s quote (and take it out of context) “O brave new world, that has such people in it.”

William Shakespeare coined the phrase “brave new world” to denote something bold and dazzling. The current meaning of “brave” refers to courage, and it takes a special kind of courage to battle something as bold and dazzling as the internet. For the past several years, Maria Schneider has waged her own battle with technology giants like Google, Facebook and Spotify. She shares her distrust of these companies with other musicians who are robbed of royalties and other income due to streaming and downloading. However, Schneider has a greater concern with the collection of personal data by these companies, and the possible ramifications to current and future generations. She has given many speeches and written several articles on the evils lurking within cyberspace, but her new double-disc set, “Data Lords” is her musical protest against the tech giants. I heard a couple of these protest works at a Schneider concert in Lakewood two years ago, and since then, I have wondered and worried about the effect this music would have on her career. After listening to both discs of “Data Lords”, I can honestly report that while much of this music is new and quite different, it represents an essential chapter in Schneider’s growth as a composer. Many of the pieces (including half of the compositions on the “pastoral” disc, “Our Natural World”) have no discernable melodies, as Schneider paints vivid pictures of scenes and situations using the short motives and punctuations of absolute music. On these pieces, the thrilling group crescendos that once heaved and sighed as a passionate outgrowth of the music, are at times, terrifying—with soloists like Ryan Keberle (trombone), Rich Perry (tenor sax), Greg Gisbert (trumpet) and Ben Monder (guitar) playing exclamatory statements over Schneider’s dense and powerful orchestrations. Schneider’s much-copied pastel chords have been replaced with new tone combinations, some of which mimic electronic sounds through acoustic instruments. Schneider has not abandoned the big band style—indeed, much of the protest music sounds like an extension of concepts developed by Charlie Haden and Carla Bley for their Liberation Music Orchestra—but she has greatly expanded her tonal palette to create these dramatic works. I won’t offer a track-by-track analysis of this album because this is music that must be experienced for both its visceral and emotional content. I will assure you that the intensity is broken up with humor and passions, and that the set contains generous portions of the lyrical Schneider style (including one piece on the protest “Digital World” disc). The CDs are not marked in sequence (i.e., disc one and disc two) but the elaborate booklet that comes with the set seems to indicate that “Digital World” precedes “Our Natural World”. That’s the order in which I listened to the discs as I prepared this review; the next time I listen, I think that I’ll reverse the discs—it might provide a completely different listening experience. Listen well to this music and heed Schneider’s warnings. They provide a grim reminder that the problems of our world are far greater than the significant issues of COVID-19, racial injustice, and corrupt governments. To complete Shakespeare’s quote (and take it out of context) “O brave new world, that has such people in it.”

KENNY WASHINGTON: “WHAT’S THE HURRY?” (Lower 9th 2020)

Bay Area vocalist Kenny Washington is no stranger to the recording studio. His  biography lists eight separate albums, including two live dates released under his own name. Apparently, he was willing to wait for the right time to record and release his first studio album, and the album’s title “What’s the Hurry?” is a light-hearted response to fans who’ve waited for this disc for many years. One benefit to the wait is that Washington brings great maturity to the music. The opening track, “The Best is Yet to Come” has become a misogynic anthem, but Washington transforms it into a slow seduction which welcomes the woman’s interaction, rather than placing her under the man’s thumb. On a sprightly duet with guitarist Jeff Massanari on “S’Wonderful”, Washington glides into an elegantly conceived melodic variation on the Gershwin tune, and closes by alternating scat and whistled improvisations. He makes “Stars Fell on Alabama” his own with a slinky tempo and minimal accompaniment (Victor Goines, tenor sax; Josh Nelson, piano; Gary Brown, bass; Lorca Hart, drums). Near the end, Washington displays his R&B chops as moves into a clear falsetto, improvising melismas set to the title phrase. After a fine voice/guitar collaboration on Harold Arlen’s “I’ve Got the World on a String”, Washington offers a soul-drenched version of Duke Ellington’s “I Ain’t Got Nothin’ But the Blues”, with Mike Olmos dishing up sassy commentary on muted trumpet. Nelson digs in to the keyboard for a hard-grooving solo, and Washington bares his soul in the final chorus. Washington and Nelson pair up for a heartfelt reading of the Rodgers and Hart classic, “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered”. Peter Michael Escovedo’s bongos introduce a Latin feel to “Invitation”, but the mood shifts to swing soon after, and the two genres alternate for the rest of the track. “Here’s to Life” was written for Shirley Horn, and in my view, she owned that song for perpetuity. Washington tackles it here, and his interpretation sounds too teary-eyed to my ears. After all, this song is a celebration of life, complete with its emotional hills and valleys. Remember that wonderful line: As long as I’m still in the game, I want to play for life, for laughs, for love. On a happier note, Washington and bassist Dan Feiszli perform a delightful version of “Sweet Georgia Brown” with swinging improvisations by both men. The band is augmented with Jeff Cressman (trombone) and Ami Molinelli-Hart (percussion) for a groovy version of “Chega de Saudade”. Goines switches to clarinet and plays an excellent solo full of spice and salsa. The album closes with “Smile”, the Charlie Chaplin movie theme that was performed by many singers at the beginning of the lockdown, in an effort to raise the spirits of those suddenly out-of-work and socially isolated due to the pandemic. Kenny Washington’s duet with Jeff Massanari hits all of the right emotions, maintaining the song’s simple message and deep pathos. This album was worth the wait, Mr. Washington.

biography lists eight separate albums, including two live dates released under his own name. Apparently, he was willing to wait for the right time to record and release his first studio album, and the album’s title “What’s the Hurry?” is a light-hearted response to fans who’ve waited for this disc for many years. One benefit to the wait is that Washington brings great maturity to the music. The opening track, “The Best is Yet to Come” has become a misogynic anthem, but Washington transforms it into a slow seduction which welcomes the woman’s interaction, rather than placing her under the man’s thumb. On a sprightly duet with guitarist Jeff Massanari on “S’Wonderful”, Washington glides into an elegantly conceived melodic variation on the Gershwin tune, and closes by alternating scat and whistled improvisations. He makes “Stars Fell on Alabama” his own with a slinky tempo and minimal accompaniment (Victor Goines, tenor sax; Josh Nelson, piano; Gary Brown, bass; Lorca Hart, drums). Near the end, Washington displays his R&B chops as moves into a clear falsetto, improvising melismas set to the title phrase. After a fine voice/guitar collaboration on Harold Arlen’s “I’ve Got the World on a String”, Washington offers a soul-drenched version of Duke Ellington’s “I Ain’t Got Nothin’ But the Blues”, with Mike Olmos dishing up sassy commentary on muted trumpet. Nelson digs in to the keyboard for a hard-grooving solo, and Washington bares his soul in the final chorus. Washington and Nelson pair up for a heartfelt reading of the Rodgers and Hart classic, “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered”. Peter Michael Escovedo’s bongos introduce a Latin feel to “Invitation”, but the mood shifts to swing soon after, and the two genres alternate for the rest of the track. “Here’s to Life” was written for Shirley Horn, and in my view, she owned that song for perpetuity. Washington tackles it here, and his interpretation sounds too teary-eyed to my ears. After all, this song is a celebration of life, complete with its emotional hills and valleys. Remember that wonderful line: As long as I’m still in the game, I want to play for life, for laughs, for love. On a happier note, Washington and bassist Dan Feiszli perform a delightful version of “Sweet Georgia Brown” with swinging improvisations by both men. The band is augmented with Jeff Cressman (trombone) and Ami Molinelli-Hart (percussion) for a groovy version of “Chega de Saudade”. Goines switches to clarinet and plays an excellent solo full of spice and salsa. The album closes with “Smile”, the Charlie Chaplin movie theme that was performed by many singers at the beginning of the lockdown, in an effort to raise the spirits of those suddenly out-of-work and socially isolated due to the pandemic. Kenny Washington’s duet with Jeff Massanari hits all of the right emotions, maintaining the song’s simple message and deep pathos. This album was worth the wait, Mr. Washington.