The last three months of 1977 were a pivotal time in my life. I was 16 years old and had just entered Greeley Central High School. I had a handful of jazz records by that time, but I was completely unaware of the music’s history and evolution until I read Marshall Stearns’ “The Story of Jazz”. I had found about two dozen copies of that book sitting on a shelf in the band room, and was told that they had been used for a jazz history class taught at GCHS a year or two earlier. Reading the book intensified my love for the music, and led me on the road to my current occupation. It was a long road, though, and I knew that I had a lot of music to discover. One day, I asked one of GCHS’ English teachers, Todd Hampton, if he happened to be a jazz fan. He was—and in a  ritual repeated by many different mentors throughout jazz history—he lent me a large pile of jazz records. Amidst several Stan Kenton records, there was the “Playboy Jazz All-Stars, Volume 2” a double LP loaded with great music and detailed liner notes. It was not the first jazz album I heard, but it was the first one I loved.

ritual repeated by many different mentors throughout jazz history—he lent me a large pile of jazz records. Amidst several Stan Kenton records, there was the “Playboy Jazz All-Stars, Volume 2” a double LP loaded with great music and detailed liner notes. It was not the first jazz album I heard, but it was the first one I loved.

Christmas was coming up, and just like the protagonist in Jean Shepherd’s “A Christmas Story”, I knew exactly what I wanted. Little Ralphie could have his Red Ryder BB gun, but I wanted a Sony mono quarter-track open reel tape recorder, model TC-105. These machines were prevalent in schools: they were well-built, dependable, and they made astonishingly good recordings. I seem to remember making tape loops on one of these recorders back when I was in 5th or 6th grade, but now I needed this machine to copy all of Mr. Hampton’s jazz records. The best feature of the TC- 105 was a little switch called “track exchange” which allowed the machine to record on each track separately. Basically, this meant that each tape could hold twice as much music: the tape could be played or recorded once through on both sides with the track exchange reading (or writing) tracks 1 and 3, then the tape could be reloaded with the track exchange switched to tracks 2 and 4 to play or record another two sides of music. My dad gave me a few not-too-subtle hints that he had found two of these coveted recorders in a local pawnshop, and that one of them would soon be mine. I scrounged up a collection of gently used reel tapes and waited anxiously for December 24. That night, my wish came true, and for the rest of Christmas break, I was parked in front of my parents’ stereo and my new recorder, taping albums non-stop. One of the first LPs I recorded was the Playboy album, and in a long-forgotten reel of home movies, I found a brief sequence of me recording that very album.

105 was a little switch called “track exchange” which allowed the machine to record on each track separately. Basically, this meant that each tape could hold twice as much music: the tape could be played or recorded once through on both sides with the track exchange reading (or writing) tracks 1 and 3, then the tape could be reloaded with the track exchange switched to tracks 2 and 4 to play or record another two sides of music. My dad gave me a few not-too-subtle hints that he had found two of these coveted recorders in a local pawnshop, and that one of them would soon be mine. I scrounged up a collection of gently used reel tapes and waited anxiously for December 24. That night, my wish came true, and for the rest of Christmas break, I was parked in front of my parents’ stereo and my new recorder, taping albums non-stop. One of the first LPs I recorded was the Playboy album, and in a long-forgotten reel of home movies, I found a brief sequence of me recording that very album.

Between 1957 and 1960, Playboy magazine released three multi-record sets featuring the winners of their annual jazz poll. Each year, the winners were picked by the magazine’s readers, through ballots submitted over a six-week period. The poll created a virtual big band with four trumpets, four trombones, a six-man sax section with clarinet, two altos, two tenors and baritone, plus piano, guitar, bass, drums as well as male and female vocalists and instrumental combo. Unlike the Metronome All-Stars, the Playboy band never assembled in a studio to record together. Instead, the Playboy LPs were compilations of recent tracks by each of the winners. Although Playboy didn’t make a big deal about it, each album included several tracks that had never been issued before. Further, the winning musicians were free to recommend the specific track they wanted included in the Playboy album. As will be clear in the following discussion, the winners comprised some of the most popular jazz musicians of the day, with an emphasis on well-established veterans and contemporary West Coast jazz players.

In preparing this Retro Review, I listened to all three of the Playboy albums again, and while there is an abundance of good music on each album, I still hold that the second volume is the strongest overall. Of course, I am biased—volume 2 was a gateway for my listening adventures—but even listening to the contents objectively, it’s hard to deny that the quality of the music is much higher, and that the album’s general concept (a night on the town) helped to focus the material.

Louis Armstrong starts the proceedings with his ebullient recording of “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails”. I had heard this Irving Berlin song before, but never sung  with the level of joy that Armstrong brought to this recording. The track, which also appeared on the Verve LP, “Louis under the Stars”, sparkles from beginning to end, with Armstrong’s exuberant reading of the verse leading to a series of choruses which build in intensity. The performance is fueled by Russ Garcia’s swinging arrangement and it peaks with a superb Armstrong trumpet solo and a jubilant final vocal chorus. Erroll Garner had visited Paris in late 1957, and in a track lifted from his double LP, “Paris Impressions”, the pianist takes us to the “Moroccan Quarter”. Rhythmically this is prime Garner, with an intense driving pulse, which is instigated by the pianist and supported by bassist Eddie Calhoun and drummer Kelly Martin. The coda is an absolute thriller with Garner literally pounding out notes from the keyboard. Surprisingly, 1958 marked the first appearance of Coleman Hawkins in the Playboy poll. The long-acknowledged “Father of the Tenor Sax” made plenty of fine recordings in the mid-to-late 1950s, so I’m not sure why Playboy chose “Blues for Rene”. The track is representational of Hawkins’ style, but it’s hardly a prime example of his art (Hawk fared better in Volume 3, which included a brilliant “Body and Soul” recorded live at the 1959 Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago). Bob Brookmeyer’s fiercely swinging “Last Chance” features the fuzzy-toned valve trombonist playing fiery choruses over the fine rhythm team of John Williams (piano), Red Mitchell (bass) and Frank Isola (drums). The first side ends with a tender performance of a then-new Vernon Duke song, “Time Remembered”, performed by guitarist Barney Kessel. Victor Feldman, then newly arrived from England, alternates melodic phrases with Kessel in the opening chorus, followed by brief, but well-constructed solos by Hampton Hawes (piano), Feldman and Kessel. The solid bass of Leroy Vinnegar and the stunning brush work of Shelly Manne make this track one of the highlights of the set.

with the level of joy that Armstrong brought to this recording. The track, which also appeared on the Verve LP, “Louis under the Stars”, sparkles from beginning to end, with Armstrong’s exuberant reading of the verse leading to a series of choruses which build in intensity. The performance is fueled by Russ Garcia’s swinging arrangement and it peaks with a superb Armstrong trumpet solo and a jubilant final vocal chorus. Erroll Garner had visited Paris in late 1957, and in a track lifted from his double LP, “Paris Impressions”, the pianist takes us to the “Moroccan Quarter”. Rhythmically this is prime Garner, with an intense driving pulse, which is instigated by the pianist and supported by bassist Eddie Calhoun and drummer Kelly Martin. The coda is an absolute thriller with Garner literally pounding out notes from the keyboard. Surprisingly, 1958 marked the first appearance of Coleman Hawkins in the Playboy poll. The long-acknowledged “Father of the Tenor Sax” made plenty of fine recordings in the mid-to-late 1950s, so I’m not sure why Playboy chose “Blues for Rene”. The track is representational of Hawkins’ style, but it’s hardly a prime example of his art (Hawk fared better in Volume 3, which included a brilliant “Body and Soul” recorded live at the 1959 Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago). Bob Brookmeyer’s fiercely swinging “Last Chance” features the fuzzy-toned valve trombonist playing fiery choruses over the fine rhythm team of John Williams (piano), Red Mitchell (bass) and Frank Isola (drums). The first side ends with a tender performance of a then-new Vernon Duke song, “Time Remembered”, performed by guitarist Barney Kessel. Victor Feldman, then newly arrived from England, alternates melodic phrases with Kessel in the opening chorus, followed by brief, but well-constructed solos by Hampton Hawes (piano), Feldman and Kessel. The solid bass of Leroy Vinnegar and the stunning brush work of Shelly Manne make this track one of the highlights of the set.

Side two opens with another ballad, J.J. Johnson’s “What’s New?” Working with a cup mute, Johnson plays a splendid melodic variation on the well-known theme, with Tommy Flanagan providing an elegant interlude to Johnson’s final chorus. Paul Chambers and Max Roach round out the group, but unfortunately, they don’t have much to do. Chet Baker’s hip and cool version of Al Jolson’s “Sonny Boy” opens a string of three consecutive tracks issued for the first time on the Playboy album. Arranged by a very young Johnny Mandel, “Sonny Boy” features a strong Baker lead in the opening chorus, swinging tenor from Richie Kamuca in the second, supremely melodic Baker in the third, incisive alto by Art Pepper in the fourth, and a half-chorus of Pete Jolly’s piano before the out-chorus. Vinnegar and drummer Stan Levey complete the lineup. The Benny Goodman track, “The King and Me”, remains one of my favorite examples of  1950s BG. André Previn composed and arranged this big band concerto for Goodman, and the star soloist shines throughout, from the brightly played opening section through the minor episode, and a fine cadenza that links back to the opening section. There was an alternate take included on the Columbia LP, “Happy Session”, but this version is better on every level (the Fresh Sound reissue includes the Playboy version as a bonus track). And if the Goodman track wasn’t brilliant enough, the follow-up is an unquestioned masterpiece. Ella Fitzgerald’s “Blue Skies” was (at the time) an unissued track from “The Irving Berlin Song Book” and it features Fitzgerald in an extraordinary two-and-a-half chorus scat solo. Unlike her famous “Lady Be Good” solo (which she repeated verbatim on several television shows of the time) the “Blue Skies” solo was completely—and undoubtedly—improvised. Paul Weston’s arrangement gives Fitzgerald plenty of room to create (including cadenzas at the beginning and end of the chart, and a wonderful saxophone background figure which Fitzgerald uses to launch her scat solo). Harry Edison provides support at times, but this is Ella’s show and she is simply amazing. (I embedded a video of this track on my review of “Ella at 100”; I encourage you to go here and take a listen. Don’t worry—we’ll hold your place in this article.) Fitzgerald’s ex-husband Ray Brown gets an equally impressive showcase. His “Solo for Unaccompanied Bass”—here re-titled “Cat without a Playmate”—is a well-structured soliloquy, complete with original melody, shout chorus, and beautifully-executed soloing. The close-miked recording captures Brown’s quick-moving fingers and his occasional breathing and grunting. The final track is another unissued gem. Recorded at the 1957 Gerry Mulligan/Chet Baker “Reunion” sessions (and later issued on the CD reissue), “People Will Say We’re in Love” is a lightly-swinging track that recalls the chemistry of the original Mulligan quartet of five years earlier. Mulligan and Baker display their fine melodic gifts, and Mulligan’s improvised backgrounds enhance the trumpeter’s solo.

1950s BG. André Previn composed and arranged this big band concerto for Goodman, and the star soloist shines throughout, from the brightly played opening section through the minor episode, and a fine cadenza that links back to the opening section. There was an alternate take included on the Columbia LP, “Happy Session”, but this version is better on every level (the Fresh Sound reissue includes the Playboy version as a bonus track). And if the Goodman track wasn’t brilliant enough, the follow-up is an unquestioned masterpiece. Ella Fitzgerald’s “Blue Skies” was (at the time) an unissued track from “The Irving Berlin Song Book” and it features Fitzgerald in an extraordinary two-and-a-half chorus scat solo. Unlike her famous “Lady Be Good” solo (which she repeated verbatim on several television shows of the time) the “Blue Skies” solo was completely—and undoubtedly—improvised. Paul Weston’s arrangement gives Fitzgerald plenty of room to create (including cadenzas at the beginning and end of the chart, and a wonderful saxophone background figure which Fitzgerald uses to launch her scat solo). Harry Edison provides support at times, but this is Ella’s show and she is simply amazing. (I embedded a video of this track on my review of “Ella at 100”; I encourage you to go here and take a listen. Don’t worry—we’ll hold your place in this article.) Fitzgerald’s ex-husband Ray Brown gets an equally impressive showcase. His “Solo for Unaccompanied Bass”—here re-titled “Cat without a Playmate”—is a well-structured soliloquy, complete with original melody, shout chorus, and beautifully-executed soloing. The close-miked recording captures Brown’s quick-moving fingers and his occasional breathing and grunting. The final track is another unissued gem. Recorded at the 1957 Gerry Mulligan/Chet Baker “Reunion” sessions (and later issued on the CD reissue), “People Will Say We’re in Love” is a lightly-swinging track that recalls the chemistry of the original Mulligan quartet of five years earlier. Mulligan and Baker display their fine melodic gifts, and Mulligan’s improvised backgrounds enhance the trumpeter’s solo.

Dizzy Gillespie fronts a 10-piece band for Melba Liston’s atmospheric “Oasis”, the opening track of side three. I didn’t care for this piece when I first heard it: the angular motives and the open scoring of Liston’s arrangement sounded primitive to me. When I finally concentrated on Gillespie’s solo, I began to recognize the track’s true worth. Like the Goodman track, Gillespie gets opportunities to blow in several different tempos and styles, and he takes full advantage of the opportunity playing astounding melodies in all ranges of his  trumpet. Paul Desmond’s “Jazzabelle” is a cool swinger taken from the altoist’s quartet album with Don Elliott. Elliott’s mellophone offers a fine foil for Desmond’s alto, and both horn men play superb solos over this simple and charming 16-bar original chord sequence. (One blogger claims that the first half of the piece is based on—of all things—the Pachebel “Canon in D”! However, the solo transcription shows that the theory is incorrect). Frank Sinatra was the clear winner of the male vocalist category with seven times the votes of his nearest competitor, Nat King Cole. Sinatra’s track is a lovely reading of “Time After Time”, a song he introduced about a dozen years earlier. Nelson Riddle’s arrangement is sheer perfection, as is Sinatra’s beautifully-paced interpretation. “¡Viva Puente!” was taken from Shorty Rogers’ big band album “Afro-Cuban Influence”, and was the flugelhornist’s exciting tribute to the legendary Tito Puente. The powerful trumpet blasts are certainly evocative of Puente, as is the powerful swing of the ensemble. Bob Cooper and Herb Geller alternate short tenor solos, followed by the wonderful Frank Rosolino on trombone and the underappreciated Rogers on flugel. Joe Mondragon’s walking bass brings back the band, with Shelly Manne and Mike Pacheco firing things up in the percussion department. The Stan Getz track was titled “Tour’s End” and Playboy’s annotator Leonard Feather was quick to assure listeners that the night was not quite over. Based on “Sweet Georgia Brown”, the track features Getz with the Oscar Peterson trio (a few years before that group carried a drummer). The swing generated by this group is palpable, with Getz gliding his smoky tone and fiery ideas on top, and Peterson and Herb Ellis contributing inventive solos over Ray Brown’s solid bass lines.

trumpet. Paul Desmond’s “Jazzabelle” is a cool swinger taken from the altoist’s quartet album with Don Elliott. Elliott’s mellophone offers a fine foil for Desmond’s alto, and both horn men play superb solos over this simple and charming 16-bar original chord sequence. (One blogger claims that the first half of the piece is based on—of all things—the Pachebel “Canon in D”! However, the solo transcription shows that the theory is incorrect). Frank Sinatra was the clear winner of the male vocalist category with seven times the votes of his nearest competitor, Nat King Cole. Sinatra’s track is a lovely reading of “Time After Time”, a song he introduced about a dozen years earlier. Nelson Riddle’s arrangement is sheer perfection, as is Sinatra’s beautifully-paced interpretation. “¡Viva Puente!” was taken from Shorty Rogers’ big band album “Afro-Cuban Influence”, and was the flugelhornist’s exciting tribute to the legendary Tito Puente. The powerful trumpet blasts are certainly evocative of Puente, as is the powerful swing of the ensemble. Bob Cooper and Herb Geller alternate short tenor solos, followed by the wonderful Frank Rosolino on trombone and the underappreciated Rogers on flugel. Joe Mondragon’s walking bass brings back the band, with Shelly Manne and Mike Pacheco firing things up in the percussion department. The Stan Getz track was titled “Tour’s End” and Playboy’s annotator Leonard Feather was quick to assure listeners that the night was not quite over. Based on “Sweet Georgia Brown”, the track features Getz with the Oscar Peterson trio (a few years before that group carried a drummer). The swing generated by this group is palpable, with Getz gliding his smoky tone and fiery ideas on top, and Peterson and Herb Ellis contributing inventive solos over Ray Brown’s solid bass lines.

Side four opens with the oldest track on the set, Jack Teagarden’s “Blues after Hours”. It’s not just that this track was recorded 10 years earlier than most of the other tracks, it sounds old and creaky. Teagarden sings and plays well (as always) and his backup group includes cornetist Max Kaminsky and clarinettist Peanuts Hucko. Still, with the exception of his duet with Louis Armstrong on “Rockin’ Chair”—which appeared on the first Playboy album—Teagarden never had a very good showcase on the Playboy compilations. The Dave Brubeck Quartet appear next with a quietly grooving arrangement of the Frank Loesser standard “Two Sleepy People”. Brubeck starts the track solo, with the rest of the rhythm coming in at the second eight. Paul Desmond remains tacet throughout the melody chorus, but plays sweetly over the rhythm in his solo. Later, Brubeck’s solo achieves a degree of complexity without raising the volume. The track ends with a lovely counterpoint between the two soloists. “Playboys Can Cook” was an improvised duet between Red Mitchell and Shelly Manne. Against the bluesy motives set up by Mitchell’s bass, Manne  juxtaposes a number of percussive sounds including fingers on the drum heads, hand clapping, brushes and mallets. The duet was recorded without the player’s knowledge, and when they heard the playback, Manne decided to submit it for the Playboy album. Like the Manne track, Bud Shank’s selection was first issued on this set. However, I’ve never been able to generate much enthusiasm for “Misty Eyes”. It’s just a run-of-the-mill original ballad, with a dull melody and an alto solo that fails to take shape until the final chorus. Like Coleman Hawkins, there were so many better choices for a Shank track. Why bother with this one? Lionel Hampton’s half-time walk through the changes of “How High the Moon” was renamed “Thoughts of a Lazy Playmate” and Feather’s notes concern the voluptuous charms of Linné, the July 1958 Playmate of the Month. However, Hampton was not thinking of this young lady when he recorded this track for Audio Fidelity, where it appeared as “Thoughts of Thelma”. The vibraphonist is fine on this track, but the then-hip combination of low-register flute and vibes has dated this track. Kai Winding’s trombone quartet with rhythm brings the album to a close with a light-hearted version of the over-drinker’s anthem, “Show Me the Way to Go Home”. Carl Fontana and Winding are the two soloists and O.B. Massingill’s arrangement delights with humorous asides and exuberant writing for the horns.

juxtaposes a number of percussive sounds including fingers on the drum heads, hand clapping, brushes and mallets. The duet was recorded without the player’s knowledge, and when they heard the playback, Manne decided to submit it for the Playboy album. Like the Manne track, Bud Shank’s selection was first issued on this set. However, I’ve never been able to generate much enthusiasm for “Misty Eyes”. It’s just a run-of-the-mill original ballad, with a dull melody and an alto solo that fails to take shape until the final chorus. Like Coleman Hawkins, there were so many better choices for a Shank track. Why bother with this one? Lionel Hampton’s half-time walk through the changes of “How High the Moon” was renamed “Thoughts of a Lazy Playmate” and Feather’s notes concern the voluptuous charms of Linné, the July 1958 Playmate of the Month. However, Hampton was not thinking of this young lady when he recorded this track for Audio Fidelity, where it appeared as “Thoughts of Thelma”. The vibraphonist is fine on this track, but the then-hip combination of low-register flute and vibes has dated this track. Kai Winding’s trombone quartet with rhythm brings the album to a close with a light-hearted version of the over-drinker’s anthem, “Show Me the Way to Go Home”. Carl Fontana and Winding are the two soloists and O.B. Massingill’s arrangement delights with humorous asides and exuberant writing for the horns.

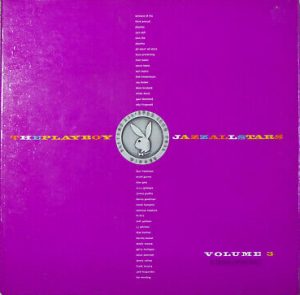

The third Playboy album was a three-record set and the first to be issued in stereo. As noted, it included excerpts from the 1959 Playboy Jazz Festival held in Chicago. Emcee Mort Sahl brought Hugh Hefner to the microphone, who asked the capacity crowd if they should repeat the event the following year. There was a hearty cheer, but somehow neither another festival nor another jazz all-stars album was produced by Playboy for two decades. The jazz festival was revived at the Hollywood Bowl in 1979, and has drawn huge crowds every year since. The 1982 festival was captured on a two-part video and on a 2-LP Elektra-Musician set. The jazz poll continued in the magazine for many years, but the cooperative venture between the record labels fell apart, and the albums became collector’s items. Incidentally, the first mention of the album title in this article will link you to discogs.com, which usually has several copies of the album for sale. However, I’ve also learned that Tom Burns of Jazz Record Revival in Bailey, Colorado has several fine copies of this album, and you can purchase one from him by emailing jazzrecordrevival@gmail.com.

The third Playboy album was a three-record set and the first to be issued in stereo. As noted, it included excerpts from the 1959 Playboy Jazz Festival held in Chicago. Emcee Mort Sahl brought Hugh Hefner to the microphone, who asked the capacity crowd if they should repeat the event the following year. There was a hearty cheer, but somehow neither another festival nor another jazz all-stars album was produced by Playboy for two decades. The jazz festival was revived at the Hollywood Bowl in 1979, and has drawn huge crowds every year since. The 1982 festival was captured on a two-part video and on a 2-LP Elektra-Musician set. The jazz poll continued in the magazine for many years, but the cooperative venture between the record labels fell apart, and the albums became collector’s items. Incidentally, the first mention of the album title in this article will link you to discogs.com, which usually has several copies of the album for sale. However, I’ve also learned that Tom Burns of Jazz Record Revival in Bailey, Colorado has several fine copies of this album, and you can purchase one from him by emailing jazzrecordrevival@gmail.com.

As for my personal history, I used the Sony recorder constantly throughout my high school years, building up an impressive collection of open-reel tapes. However, when I bought a stereo cassette deck a couple of years later, the only recording I copied from the original reels was this Playboy album. I had that cassette for nearly 25 years before I found a copy of the vinyl for sale. Listening again, it remains one of my all-time favorite albums. Some love affairs are eternal.