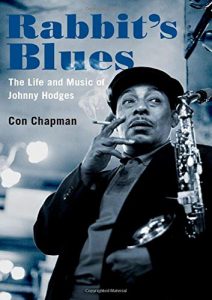

Johnny Hodges was an enigma. Situated in his familiar perch in the middle of Duke Ellington’s saxophone section, he maintained a passive composure regardless of the activity around him. He was a private man who rarely granted interviews (and sometimes skipped out after only a few questions). Self-taught on both alto and soprano saxophones, he was not particularly well-versed on the mechanics of music, and the fear of being asked to explain elements of his personal style may have been his reason for keeping the press at arm’s length. Still, his unique approach to the horn made him one of the most popular jazz musicians of his era, and his thrifty money management allowed him to leave a substantial estate at his death. With an overall shortage of first-hand  information—but plenty of famous anecdotes—the challenge to develop a chronological history of Hodges’ life is quite significant, but in his new book, “Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges” (Oxford), Con Chapman skillfully combines scraps of information to present the most comprehensive biography of Hodges we’re likely to see.

information—but plenty of famous anecdotes—the challenge to develop a chronological history of Hodges’ life is quite significant, but in his new book, “Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges” (Oxford), Con Chapman skillfully combines scraps of information to present the most comprehensive biography of Hodges we’re likely to see.

Chapman establishes Hodges’ true birth date as July 25, 1907 (earlier sources cited his birth one year earlier), and that the name “Johnny” did not appear in any form on his birth certificate (his birth name was Cornelius). Chapman even notes that the family name varied from “Hodge” to “Hodges” throughout the years. He explains Hodges’ curious nickname “Rabbit” (which he gained long before his extended stint in the Ellington organization), his introduction and friendship with Sidney Bechet, and his early experiences playing in both Boston and New York. Hodges’ two wives and his mistresses are also discussed, along with a few details of his relationships with his children. We discover Hodges’ rivalry with fellow alto saxophonist Benny Carter (capped by an extraordinarily disrespectful incident at the Newport Jazz Festival), and of his tempestuous relationship with Ellington. As is well-known, Hodges was the highest-paid member of the Ellington band, and while he certainly earned his pay from his outstanding solos and section work, Chapman notes several unprofessional acts that would have gotten him fired from a less magnanimous bandleader (i.e. showing his dislike of a new piece composed by Teo Macero by standing up during the run-through and tearing his part in half; or brazenly stating that he wasn’t going to show up for a performance of a Sacred Concert—even though many of the pieces featured him!)

Unfortunately, Chapman is more of a cultural historian than a jazz specialist. His previous work includes several plays plus books on baseball, the Supreme Court, poetry, cats and human sexual relations. The greatest weakness of “Rabbit’s Blues” is that Johnny Hodges’ music is barely discussed. Want to learn more about the musical chemistry between Hodges and Ellington’s greatest vocalist, Ivie Anderson? You won’t find it here, even though there are dozens of incredible recordings of them together. The entire 30-year collaboration of Billy Strayhorn and Hodges gets reduced to a single 10-page chapter! The astonishing Blanton/Webster band of 1940-1942 is covered in just 6 pages. Chapman seems to be a “moldy fig”; someone with little interest in or knowledge of post-WWII jazz. He has no use for Charlie Parker, even though Parker admired Hodges’ work. John Coltrane, one of the members of Hodges’ small band in the early 1950s is remembered more as a heroin addict—the reason for his dismissal—than for his burgeoning talent. Oddly enough, the most famous example of a moldy fig jazz writer was Stanley Dance who was one of Hodges’ and Ellington’s biggest supporters. While Dance’s work is cited and quoted throughout this book, Chapman is rather rude to his predecessor, at one point quoting a musician who characterized Dance as a sycophant.

Normally, the lack of substantial musical discussion would be enough to disqualify a book like “Rabbit’s Blues” from a review on this site. However, I recognize the value of Chapman’s research on Hodges’ life story, and I realize that with the declining number of Hodges’ friends and relatives, we may never get his full biography. So while I cannot recommend this book without serious reservations, I will offer the following appendix of five classic Hodges solos—all with brief discussions of the music and embedded YouTube clips. If you don’t agree with my selections, that’s fine—there are many other fine examples of Hodges to select. Here’s what you should have learned from a Johnny Hodges biography.

“FUNKY BLUES” (“Norman Granz Jam Session # 1” LA; June 17, 1952)

Naturally. The one opportunity we have to hear Johnny Hodges, Charlie Parker and Benny Carter playing the blues in back-to-back choruses. Hodges starts his solo on the last four bars of the melody, and creates a poetic improvisation as notable for its silences between phrases as for his impeccable note choices. Parker’s follow-up displays the easy transition between the swing and bop approaches to the blues, and taken together, the solos of Hodges and Parker reveal a similar architecture in the placement of phrases. By the time of this recording, Carter had already begun to absorb elements of Parker’s style without losing the unique parts of his own approach. His solo offers a synthesis of the two styles. Long considered a classic jazz recording, Chapman barely touches upon this track (using a rather generic quote from J.J. Johnson instead of providing his own comments) before moving elsewhere.

“PRELUDE TO A KISS” (“Ellington Indigos”, NYC; October 1, 1957)

Probably my earliest exposure to Hodges, and still one of my favorites, this brilliant showcase for the alto saxophonist displays him at his most rhapsodic. In the first chorus, Hodges’ saxophone sighs and moans as he as he caresses “Prelude” like a long-time lover. The first bridge maintains the gentle approach with a superbly-played duet with baritone saxophonist Harry Carney, but at the end of the 8-bar passage, Hodges hints at what is yet to come. The piece climaxes in the second bridge, as Hodges throws a multitude of ideas at the listener. In the hands of a lesser player, the confluence of motives would be a hopeless muddle, but. Hodges pulls it all together with the sheer passion of his conception, and tops it all off with a dramatic return to the melody. Throughout the book, Chapman obsesses over Hodges’ use of glissandi, but this version of “Prelude” shows how he used the effect to heighten his interpretations.

“TONIGHT I SHALL SLEEP” (“Unknown Session”; LA; July 14, 1960)

Chapman quotes Dance about Hodges’ ability to sing through his horn. Why Chapman didn’t cite any examples of this concept is beyond me. On this septet date—left unissued until a few years after Ellington’s death—Hodges effortlessly plays a vocally-inspired rendition of this under-appreciated Ellington song. Even if you don’t know the words to this song, start with the title on the opening phrase, and Hodges will give you a fairly good idea of what follows. So, just for fun, listen to Hodges first, and then listen to Sarah Vaughan’s glorious recording (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhJycCBvWh4). But before you leave Hodges’ recording behind, marvel at how much emotion he draws from this melody with a minimum of filigree.

“BLUE PEPPER (FAR EAST OF THE BLUES)” (“Far East Suite”; NYC; December 21, 1966)

For the record, I love Hodges’ glorious reading of Strayhorn’s “Isfahan”. However, with another (and arguably greater) Strayhorn ballad coming up, I chose “Blue Pepper” as an interesting look at Hodges in the mid-1960s. As a composition, “Blue Pepper” is not one of Ellington’s masterpieces. It is a forced pairing of contemporary rock with exotic music from the Middle East. Yet Hodges commits to the mix completely, offering a rough-edged blues solo that digs into the tune’s rhythmic infrastructure. He fits right in with Rufus Jones’ driving beat and Ellington’s percussive piano, and he maintains the spirit by keeping his solo simple and direct. Hodges’ small band of the 1950s flirted with rhythm and blues with their hit “Castle Rock”, but “Blue Pepper” gave Hodges’ the opportunity to face the rock and roll challenge head on.

“BLOOD COUNT” (“And His Mother Called Him Bill”; NYC; August 28, 1967)

Chapman does discuss Billy Strayhorn’s final composition, but curiously never talks about Hodges’ moving realization of the score. After nearly three decades of collaboration, Hodges knew that “Blood Count” would be the last chance he would have to play one of Strayhorn’s ballads. He plays the opening melody with great tenderness, but as on “Prelude to a Kiss”, he lets his emotions loose on the bridge. His tone reveals the deep hurt he feels, and as the arrangement surges under him, he lets go one of the most passionate cries ever to emerge from his horn. Death took Strayhorn at the tender age of 51, and just under three years after this recording, Hodges died—two months short of his 63rd birthday.

Con Chapman has served Johnny Hodges well as a historical biographer, but it remains for a musically astute jazz historian to fill the remaining gap by exploring the rich musical legacy of Hodges’ music. Hodges deserves that treatment, many times over.

The video recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.