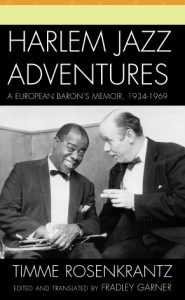

Timme Rosenkrantz was born into a Danish royal family that traced its lineage to the Rosencrantz character portrayed in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”. Rosenkrantz developed an abiding love for jazz and spent a good part of his life in New York City listening—and later promoting—the music. His memories of his time in the US have been collected in the book “Harlem Jazz Adventures”. Most of the text was written in his native Danish tongue in 1964; in the following year, Rosenkrantz and his longtime companion Inez Cavanaugh, created an unpublished English translation. For the current edition, published by Scarecrow Press, Fradley Hamilton Garner has compiled and adapted both versions of the text and added material from Rosenkrantz’ other published works.

Timme Rosenkrantz was born into a Danish royal family that traced its lineage to the Rosencrantz character portrayed in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”. Rosenkrantz developed an abiding love for jazz and spent a good part of his life in New York City listening—and later promoting—the music. His memories of his time in the US have been collected in the book “Harlem Jazz Adventures”. Most of the text was written in his native Danish tongue in 1964; in the following year, Rosenkrantz and his longtime companion Inez Cavanaugh, created an unpublished English translation. For the current edition, published by Scarecrow Press, Fradley Hamilton Garner has compiled and adapted both versions of the text and added material from Rosenkrantz’ other published works.

Rosenkrantz first came to New York in February 1934. After being warned that Harlem was too dangerous for whites, Rosenkrantz went there anyway. He had an uncanny knack for meeting all the right people. On his first night in Harlem, he met John Hammond at the Savoy Ballroom, where he heard Chick Webb’s big band and Al Cooper’s Savoy Sultans. Later that night, Rosenkrantz and Hammond went to Pod’s and Jerry’s and heard Willie “The Lion” Smith accompany Billie Holiday. As the narrative progresses, the list of legends grows longer: Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, Eddie Condon, Benny Goodman, Art Tatum and Fats Waller. But Rosenkrantz’ memoir is even more valuable when it talks about lesser-known musicians like Leo Watson, Adrian Rollini and Herman Chittison. Ever heard of trumpeter Jake Vandermuellen? How about guitarist Zeb Julian? Me, neither. Rosenkrantz makes these forgotten musicians into mythic heroes, and his discussions of these musicians are both poignant and telling.

Starting in the 1940s, Rosenkrantz produced jazz concerts, jam sessions and his own privately-made recordings. Unlike Norman Granz, Rosenkrantz seemed unable to turn a profit on his efforts. His most famous concert was presented at Town Hall on June 9, 1945. The performers included several of Rosenkrantz’ friends, including Gene Krupa (who reportedly played the concert for free), Bill Coleman, Teddy Wilson, Don Byas, Slam Stewart, Stuff Smith and Red Norvo. Most of the performances were issued on Commodore, including the iconic Byas/Stewart duet version of “I Got Rhythm” which appeared on “The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz.” Rosenkrantz’ account of the concert is maddingly brief— taking up just over four pages—and has a few factual errors. Garner, as he does throughout the book, corrects the mistakes through footnotes, or at the very least, leaves in the most plausible story.

Garner is not infallible, especially when it comes to recordings. He fails to note that Duke Ellington’s 1943 Carnegie Hall Concert has been available for the past 35 years on Prestige, and he wrongly includes Thelonious Monk on the Coleman Hawkins recording sessions that included “Woody’n You” and “Disorder at the Border”. There is an extensive discography included in the back of the book which is loaded with intriguing unissued sessions, but is laid out in a confusing manner (for example, the Town Hall is split up into several listings over multiple pages). What emerges from the discography is the wish that someone would collect and compile these unissued recordings and release them on CD. And while they’re at it, how about a complete version of the Town Hall concert on CD? There are plenty of recorded gems from that afternoon which should be available.

Rosenkrantz died in 1969, and footage of his memorial concert (with Ben Webster, Teddy Wilson and Inez Cavanaugh) is included on the Shanachie DVD, “Ben Webster: Tenor Sax Legend/Live and Intimate”. Taken alongside his witty and warm remembrances, one gets a feeling for a very special man, who had a deep love for jazz. While Timme Rosenkrantz never got rich promoting jazz, the love and respect he had for the musicians was reciprocated many times over.