Former Jazz History Online contributor Amy Duncan passed away in June 2018, alone in her apartment in Rio. In addition to her skills as a journalist—she was best-known as a jazz and features writer for the Christian Science Monitor —she was an outstanding pianist, composer and arranger. To me, she was also a mentor, friend and colleague.

With the exception of a single Facebook post by jazz critic Chip Deffaa, no obituaries or memorials have appeared in print or online since Amy’s passing. What follows is a remembrance and celebration of Amy from friends, family, musicians and colleagues. Obviously, we cannot cover all of Amy’s life in the same detail as Amy did in her autobiography, “Getting Down to Brass Tacks”. Further, many of the remembrances below had to be edited to keep this article at a manageable length. The memories are arranged in approximate chronological order. I’ll add notes (in italics) to fill in some of the inevitable gaps.

To get the complete picture, we recommend that you listen to some of Amy’s music while you read the memories below. Two of Amy’s albums, “The 80s Demos” and “My Joy” are available on YouTube. Follow the links to open these playlists in separate windows.

THOMAS CUNNIFFE

Amy Hildreth Duncan was born in New York City on December 5, 1941 to Bob Duncan and Edith Bates. Bob was a fun-loving alcoholic, while Edith was down-to-earth and a stern taskmaster.

My mother was a fascinating dichotomy of pragmatism vs magical thinker, social butterfly vs loner, self-effacing self-promoter. She had her mother’s Yankee practicality and her father’s dreamy wanderlust. I like to think my sister and I inherited a little of both.

HILARY ALEXANDER, Amy’s younger daughter.

Not surprisingly, the marriage was tumultuous, and Amy found solace with her older sister, Bertie. Amy describes the following childhood scene, which took place in their home in Newtown, CT.

The most fun Bertie and I had together was in the winter. There was always a lot of snow and the wind would sometimes blow it into drifts that rose above our heads. To me there was nothing more beautiful than the snow falling silently all night long and then waking up to a white world the next morning. We considered ourselves lucky to have not one, but two hills in our very own yard. We used to slide down them on our sleds, on pieces of cardboard and on simple wooden skis that had straps we slid over our boots. When we got a little older and more daring, we’d drag our sleds down the road to a really big hill on a wide paved road. There was hardly any traffic in those days, especially when the roads hadn’t been plowed, so we and the few other kids in the neighborhood had the hill pretty much to ourselves. It was a big thrill to go down that hill on our sleds—it was so steep and so fast!

AMY DUNCAN, “Getting Down to Brass Tacks”, 2012.

Amy and Bertie were creative, talented kids: making hand puppets; sewing dolls; learning musical instruments; later, languages; and converting a dresser drawer into a six-room doll’s house with flooring made from surplus plastic tiles from the local Scrabble factory. Some of the furniture was purchased (bathroom fixtures, a bed and dresser), but most was crafted from painted cardboard, fabric, pipe cleaners, and yarn.

MOLLY RENDA, stepsister.

When the girls were teenagers, Bertie discovered boys, and Amy discovered jazz. Before long, Amy was gigging as a pianist in local clubs on the weekends.

One day Pop came back from New York with a present for me that neither he nor I imagined would have the far-reaching effects it did. It was an LP of a blind jazz pianist named Alex Kallao. I put it on the turntable and sat down to listen. I couldn’t believe what this chubby little blind man could do at the piano. It absolutely took my breath away….[A] powerful, indescribable feeling came over me, and I suddenly thought, “This is what I want to do—this is what I want to be!”…So from that day on, I spent all my free time practicing the piano, and never swerved from my goal, even though I didn’t have a piano teacher anymore.

It was the 1950s and nobody studied jazz…It wasn’t like today, when a lot of high schools and even junior high schools have jazz bands…Finally one day…I begged Ma to let me go into a music store, and I found the only book they had that explained about chords. It was a guitar book…but it was better than nothing. I taught myself from that book, and from jazz records by Charlie Parker, Dave Brubeck, Gerry Mulligan, and Thelonious Monk….

I saved up my money and got a subscription to Downbeat magazine….I even entered their “My favorite jazz record” contest, and to my surprise and delight, I won first prize, probably because I was a kid more than for the quality of my review. “Ellington at Newport” was my choice, and the folks at Downbeat sent me a copy of Leonard Feather’s “Encyclopedia of Jazz” as my prize. I never dreamed that one day I would be a real jazz critic and get the chance to hang out with Feather himself at jazz concerts.

AMY DUNCAN, “Getting Down to Brass Tacks”, 2012.

Amy and I became close friends in Newtown High School. We were loners, selective loners. We mutually loved jazz. She had an ear for music, rhythm, beat and lyrics. I always learned a lot from her. She was courageous, generous and kind. I always envied her spirit. She was a free agent with talent. We had great warm times together. I wished that she stayed and we could have seen each other forever.

SARA LEDERMAN, high school friend.

As teenagers, my sister and I were great fans of vocalese, especially Lambert, Hendricks and Ross. We were also the two best French students in high school and inveterate Francophiles throughout college, so imagine our delight and joy when we first heard about the Double Six of Paris—we couldn’t imagine anything cooler than vocalese sung in French, and when we finally heard the group, we couldn’t believe our ears! The first album we bought was “Swingin’ Singin’,” and we became lifetime fans of the group. One of the first things that caught my attention on the recording were tunes that had been recorded by the Gerry Mulligan Tentette, such as “Westwood Walk,” “Boplicity,” and “A Ballad.” I practically knew the instrumental solos by heart, so it was great fun to hear them sung for the first time—and in French! The singers expertly captured the phrasing of the original instrumental soloists, and managed to pull off some really incredible vocal gymnastics without going off pitch.

AMY DUNCAN, reviewing Les Double Six’s “Singin’ Swingin’”, Jazz History Online, November 2012

Although Amy wanted to go to the Berklee School of Music, Edith would not support her daughter’s proposed music career. So Amy attended Boston University, along with Bertie. Amy continued to play jazz piano gigs, and one fateful night, she went to see the film “Black Orpheus”, which set the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice during carnival in Rio. Meanwhile, back at home, the long-divorced Edith had fallen in love again. Molly Renda learned how to be cool through her new stepsisters.

My father, George, met Edith in the 60s, and I would spend Sundays at the house entertaining myself with [Amy and Bertie’s] doll house and a bucket of old Scrabble tiles. I was getting familiar with Amy and Bertie through their stuff and stories about them. I met my step-sisters for the first time in the house where they grew up, on Birch Hill Road in Newtown, Connecticut. I was about nine (1962). They were in college. I was in the fourth grade. They were cool, and this was a time when I was very invested in figuring out how to be cool myself. The wood-paneled bedroom they shared as children was not very brightly lit. A print of a Renoir painting hung above the table lamp between the twin beds, the willow slat shades drawn. They showed me where things I might like to play with were stored in the closet, including more dolls. “I don’t play with dolls,” the cool me remarked. “Well (pause), that’s too bad,” replied Amy. I got it, then, that I had a lot to learn from these two. And over the years we relished our Step-Sisterness. We loved and appreciated the crazy-quilt patchwork of our family connections. And we did learn a lot—from each other, and in support of each other.

MOLLY RENDA, stepsister.

By 1962, Amy was married to a black man named Ron Boutté, and in June, Amy gave birth to her first daughter, Madeleine. Amy was gigging around Boston and learning about avant-garde jazz. Unfortunately, she also picked up a drug habit. The next decade found her in a dizzying series of adventures. By 1964, she had dropped her drug habit and had taken up macrobiotics, both for her diet and her lifestyle. She stopped playing piano and listening to music, focusing her life on cooking nutritious meals. Her marriage to Ron was in trouble, so Amy took Madeleine with her on an extended trip to Mexico, where the pair stayed with Amy’s father and his new wife, Marí. Two years later, Amy and Madeleine returned to Boston, where Amy divorced Ron and took up residence in a cold water flat. Ron’s soon-to-be second wife describes her first meeting with Amy:

Ron and I had just started dating. One afternoon I made him beet borscht. He had never had it before and thought it was quite exotic and proclaimed it delicious. “I must call Amy and tell her about it. In fact let’s go by and give her some.” I was upset and jealous that Ron wanted to give my soup to his wife (they weren’t divorced yet.) Yet we drove to Amy’s apartment after Ron’s prodding. I sat in the car waiting for him to hand off the soup and come back to the car. But Amy came to the car window all smiles and welcomed us in. I thought, “My God! Do I have to be a friend too?” Her warmth convinced me to go in. We had a great time after I let my jealousy go.

SALLY BOUTÉ, Ron’s second wife and Amy’s friend.

One time she went to Mexico with Madeleine—a young child then—she came to visit my parents residing in Texas at the time. As I remember she stayed a day or two. My Mom was thrilled to have her there with a small child! I was there for a day and we had a good time talking.

LIBBY UNWIN, cousin.

Amy was a genuine Beatnik. She introduced me to: Umeboshi plums (the macrobiotic staple), “Black Orpheus” (the movie) and Jon Hendricks (the music—and, one time in NY, the person!)

MOLLY RENDA, stepsister.

In 1972, shortly before the birth of her second daughter, Hilary, Amy’s life took another turn. After an accident which nearly caused Madeleine to lose part of a finger, Amy decided to try Christian Science. She followed this religion for the rest of her life. Amy already had a distrust of traditional medicine (which became a fatal belief). Hilary was born under natural childbirth, and the family—including Amy’s new Brazilian husband João Alexandre—lived in a cramped apartment in Jamaica Plain, near Boston. Amy saw the need for a larger home, but João could not afford it, and he objected to Amy working outside the home. The marriage was already in trouble (João disliked the macrobiotic diet) so Amy found a job at the Christian Science Center. She met trombonist Ben Alarcón, who convinced her to take up the piano again. Amy started gigging, divorced João, and took lessons with a legendary jazz piano teacher.

I can’t remember how I first heard of Charlie Banacos, but it must have been from some musician I knew who had studied with him. In the middle 70s, Charlie was teaching in a studio in Brookline, MA, not far from where I lived. He arrived at his studio early in the morning and taught all day long, every day. When I met him, he was no longer performing, and even though he was an accomplished pianist, he had no interest in putting his work “out there.” Teaching was his mission. I took the trolley to Brookline and knocked on the door to his studio. The door opened, and there was Charlie—younger than I had expected, wiry, with dark hair and eyes that sparkled with amusement and an intense energy that I could feel before he said a word. I felt at home right away. Little did I suspect what he would put me through! We started out with exercises on “Autumn Leaves” that took me through 12 keys and every possible chordal and scale combination. And that was just the beginning—before long he had me transcribing complex solos by jazz greats like McCoy Tyner and Bill Evans. I worked as hard as I could so I could hear him say, “That stuff is cookin’!” Even though Charlie was always affable, very funny, and almost childlike, he meant business. I had to practice five hours a day to be able to go to class and not make a total fool out of myself. I couldn’t help laughing, though, when I’d sit down at his old upright piano to show him how I’d done that week. He’d stand over me with a hammer in one hand and a screw driver in the other, with a fiendish grin on his face! All of Charlie’s lessons were handwritten, and he’d punctuate his almost illegible writing with humorous cartoons. I was always dumbfounded by how he could be so funny, open, and relaxed with everyone and still command so much respect. I guess it gets down to the fact that he was simply a genius, and I don’t use that word lightly. Charlie died way too young, and left countless students who genuinely loved him, including me, in mourning. What a great spirit he was!

AMY DUNCAN, Finally Getting Down to Brass Tacks, August 23, 2016

I knew Amy by some conversations we had in the Charlie Banacos students Facebook group—we were both Charlie’s students. We shared some resources back and forth. She was nice, knowledgeable and was doing some good work!

DAVID ASKREN, guitarist and educator.

When she moved to Boston, we connected and saw each other frequently. I saw her play at the Blue Note and Top of the Hub in Boston many times. SARA LEDERMAN, high school friend.

Amy’s family ties remained strong, and the multiple generations of intelligent, strong-willed women became a formidable coalition, as recalled by Bertie’s two sons.

Auntie Amy was the other half of sister-ship with my mother, Bertie. The laughter and silliness that came from that team, with Madeleine, Hilary and Edith mixed in, was such a joy to be part of—not just for its volume but for the love and wisdom that was somehow part of their collective sense of humor. We were lucky to be part of such wit, even better due to the high intellect that was its source. Somehow, Amy was the center of this craziness, bringing up a topic and bouncing it off my mother. It was a joy to be among such giants of women.

PHILIPPE DOUCET, Amy’s nephew.

I will always remember my Auntie as someone with a keen intelligence who always strived to find a deeper meaning in life through carving her own spiritual path. She was passionate about expressing her musical abilities and had a devilish sense of humor. I remember going to our grandmother’s house with Amy, my cousins Mad and Hil, my brother and mother and George and having the most wonderful family gatherings during the holidays. Amy was always integral in these reunions. Once she set her mind on an important decision, she always stood firm on what she wanted to do and no one could sway her. She was never someone who was afraid to stand up for herself and was never afraid to tell you the truth even when you didn’t want to hear it. Her brutal honesty was refreshing and she was never timid about expressing how she felt. I personally asked her advice on many occasions as I always valued her perspective on life. I will miss my one-on-one deep conversations and I love her as any nephew would.

ERIC DOUCET, Amy’s nephew.

Amy, in particular, always gave me the sense that everything would be all right and that it would all work out, no matter what. It was her sense and confidence which she also gave me that I remember and cherish the most. My brother and I could talk to her for hours. We loved hearing her thoughts and sharing ours with her. She was a life force, and still is to me. I love you, Auntie!

PHILIPPE DOUCET, Amy’s nephew.

Around 1980, Amy decided to move to New York City. Madeleine was working out of state most of the year, but Hillary was still in school, and Amy wanted to keep Hilary’s life as stable as possible during this transition. So Hilary moved in with Bertie and her family, while Amy established herself in the Big Apple. She was still working for the Monitor, so all she needed was a steady piano gig to add to her regular income. Soon, Hilary and Amy shared an apartment in Manhattan.

I think I remember her best from the years we spent alone in our midtown Manhattan studio apartment in the early 80s. She was doing cocktail piano gigs around town while writing jazz and rock reviews for The Christian Science Monitor, which had the side benefit of free entry to various jazz concerts and festivals that I also attended. On weekends we’d see obscure Japanese art films from the 1950’s at the Japan Society or spend long languid afternoons with a jar of iced mint tea at Central Park’s Sheep’s Meadow. Sometimes we’d join our gay neighbors for a Dynasty watching party on their TV (we didn’t have one) or visit her glamorous Aunt Ruth Dubonnet to hear her tales of being a Broadway backer in the 1950s. My mother was very cultured, curious, and engaged. There’s no doubt in my mind that the cultural stimulation she provided me at such a young age, the exposure to live jazz in particular, directly led to my current career running an event that celebrates live jazz, swing dancing and singing with a big band that performs all over the world.

She was always restless and dissatisfied, wishing the artist’s wish that she could make a living just doing what she loved, playing piano and writing music and nothing else. As with most, this reality was beyond her grasp. Still, her kindness and enthusiasm was contagious, and I’m delighted that so many people remember her fondly and think of her as the person that reached out just when they needed it the most.

HILARY ALEXANDER, Amy’s younger daughter.

Amy was always friendly and warm towards me. She would invite me to her jazz performances which I so enjoyed. She spoke at least three languages and moved from one to the other with ease. She not only played jazz, she wrote it! And when it was very unusual for a woman to be the head of a jazz group, there was Amy with her own trio. She was an expert at macrobiotic cooking. She became the music editor for the Christian Science Monitor. Amy never bragged or made anyone feel like less. She was a regular girl, and actually befriended some odd people who were lonely. She had compassion, kindness, humility and so many gifts.

SALLY BOUTÉ, friend.

After attending the Kansas City Women in Jazz Festival, Amy was offered a job playing at a summer resort. The job was not as advertised, but what started as a “gig from Hell” suddenly took a life-changing turn.

I first met Amy in the early 80’s when several of us were playing in Bailey’s Harbor, Wisconsin in several different jazz clubs. In a short time, I came to find out she was not only a great jazz pianist, but also an outstanding composer and arranger, and a contributing writer to the Christian Science Monitor.

GENE AITKEN, former Director of Jazz Studies, University of Northern Colorado.

I met her in Door County Wisconsin back in the 80s. I was playing up there with Gene Aitken and she was playing a solo piano gig in a country club. We all started hanging out together and she came and sat in with our group. I also visited her in New York and we went to some clubs together. Then Gene started bring her in to write about the Greeley festival. She was great to hang with and a lot of fun. Good player too.

TOM MORGAN, drummer, educator (and UNC alumni).

I don’t recall who told me that a guest jazz critic was coming to review the UNC/Greeley Jazz Festival. All I knew was that I needed to meet this person, as I was exploring the same career track. Amy and I hit it off from the start, and we would hang out every year at the jazz festival, and talk on the phone whenever we could. I knew that I wanted to continue performing while working as a critic. Amy was the first person I knew who did both. She became a trusted mentor and friend.

THOMAS CUNNIFFE, Jazz History Online (and UNC alumni)

Amy’s critiques were funny, informative and insightful. She even managed to single out one of my scat solos!

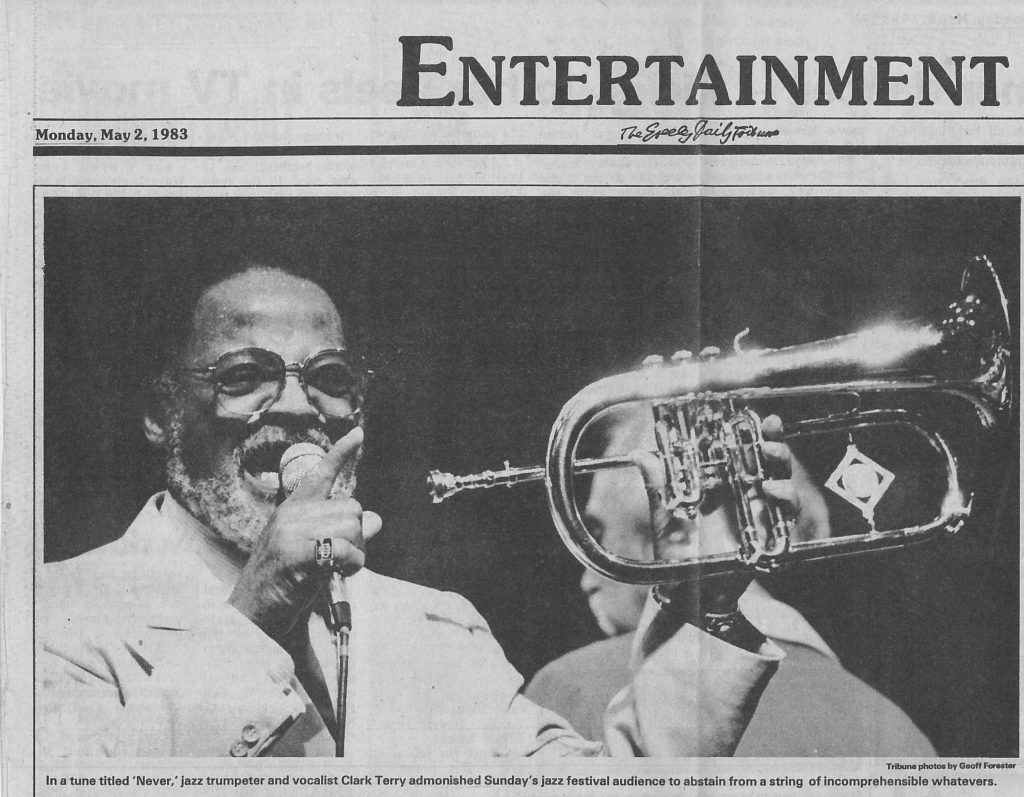

Greeley Tribune, May 2, 1983.

His weird and wonderful nonsense jargon sounds like a mixture of Swedish, German, Russian, and the crazy jabber of another singing horn player, trombonist Richard Boone, formerly of the Basie Band. He sang a tune entitled “Never,” in which he admonished the audience to abstain from a whole string of incomprehensible whatevers, and “Mumbles,” a blues with a long monologue tagged on the end, which qualified as a true epiglottal tour de force.

AMY DUNCAN reviewing Clark Terry’s performance at the UNC/Greeley Jazz Festival, Greeley Tribune, May 2, 1983.

Although Rare Silk was the official evening concert headliner, it was UNC Vocal Jazz I, directed by Mark Israel, that really stole the show. The group sang with absolute confidence and swinging precision. In addition, they had the best bunch of scatters of any of the jazz vocal groups. Several of them traded solos on Roger Treece‘s “A Little Minor Blues,” and they all (especially Tom Cunniffe and Brenda Russell) showed fine musicianship and a good jazz feel.

AMY DUNCAN, Greeley Tribune, May 2, 1986

After three years of coming out here and observing the UNC/Greeley Jazz Festival, I’m becoming more and more aware that jazz education in the West and Midwest is a revolution of sorts. Many fine jazz players are coming out of these programs and are changing the face of jazz across the country. They’re bringing a lot of knowledge, discipline, and experience with them, and this tends to raise the level of musicianship across the board.

As I was pondering these things, I wondered—what about the students who play for a while in a high school or college band and then lose interest and move on to something else—what did they get out of it? Well, aside from learning to appreciate jazz and broadening their horizons, I believe the young people who have had the privilege to be part of a stage band or vocal jazz ensemble have learned some things that will stand them in good stead, no matter what they do. It may sound corny, but let’s face it, to make good music—any kind of music—you’ve got to exercise some qualities that no adult can afford to be without: discipline, self-control, order, discrimination, attention to detail, ability to see the overall picture, cooperation, perseverance, patience—I could go on, but you get the point.

Now consider this: With jazz, you have to go a step further. You see, there’s this improvisation business. What does it take to improvise? Well, it takes all of the aforementioned qualities, plus a couple more: courage and honesty. You know, it’s been said that among artists, the poet is the most courageous because he puts his soul on the line. Well, isn’t that also true of the improviser? Improvisation is a mirror—the jazz musician plays what he or she is.

So, as I head back to the Big Apple, I’m thinking about this jazz education movement and its far-reaching implications, and I’m glad there are people like Gene Aitken around, and the host of jazz educators and clinicians who are making it happen. Thanks, folks.

AMY DUNCAN Greeley Tribune review, April 29, 1985.

At one of the Greeley concerts, Amy heard the UNC Euphonium/Tuba Jazz Ensemble, led by UNC trombone professor, Buddy Baker. Amy was immediately captivated by the sound of the low brass group. Soon after her return to New York, she formed her own ensemble, Amy Duncan & Brass Tacks.

I met Amy when a friend of mine recommended me for her 10-piece band, Brass Tacks. We became good friends and she was always fun to hang out with. Amy would put others before herself and was very helpful to people in many ways.

JOHN JENKINS, jazz drummer.

Meanwhile, back in Greeley, I was preparing an audacious undergraduate Honors Project. I planned to teach a semester-long jazz history course, complete with my own newly-written textbook, and an audio history of the music spanning from 1902-1988. My advisor told me to start by creating a syllabus, and to send it to friends whose opinions I trusted. Amy was one of the recipients. I was a little unsure of my teaching abilities, and the syllabus contained a few veiled apologies. Amy would have none of that! She chided me for my insecurities, and assured me several times that I was more than qualified to teach the subject. Well, she was right. My course was very successful, and my work was awarded the Best Honors Project of the Year.

THOMAS CUNNIFFE, Jazz History Online.

In over fifty years of performing in the jazz and concert worlds, Amy Duncan was one of my favorite collaborators. As a pianist, composer, percussionist and writer, she joined me in helping to create a concert stage for tap dance. Every Monday for weeks, I performed with her trio at the famous Blue Note club in Manhattan, and we created a full-length concert work together, “Cantata and the Blues” which incorporated some of her fabulous original compositions, “Waterways” and my favorite, “Monk Creeps In”.

BRENDA BUFALINO, tap dancer.

In 1992, I moved to New York City to take a job at Stash Records. Amy was living in Greenwich Village, and we found a night to have dinner and talk. By this time, she had married and divorced again, Madeleine and Hilary were rooming together elsewhere in the city, and Brass Tacks was working on a regular basis. That night’s dinner was a futile attempt to convince me that New Yorkers could make Mexican food. All Amy wanted to talk about was Brazil and its music. I was fascinated and impressed with her knowledge and enthusiasm. About a year later, Amy packed up and moved to Rio.

THOMAS CUNNIFFE, Jazz History Online.

Amy came back to the US after a stay in Rio, but by 1999, she moved there permanently. She described many of her experiences in detail in the pages of her memoir. She assembled a new edition of Brass Tacks, and recorded an album, “My Joy”. She made some new friends in Brazil, but only a few of her American friends came down to visit. Facebook became a primary method of communication.

I first met Amy Duncan in the early ’90s, when one of her daughters and I began dating. To say Amy was unlike the mothers of my other peers is a huge understatement. It’s fair to say I didn’t “get” everything about her freewheeling nature, but the part I did get I embraced dearly until it somehow became part of my own essence. Of course, I’m referring to Amy’s talent and especially her passion for music—not just as a jazz pianist and bandleader but also as a champion of Brazilian sounds and culture. I knew a few things about that nation’s samba, bossa nova, and popular musical traditions prior to our meeting, but Amy’s Brazilian mixtapes opened a door that I leapt through with an open mind and curious ears. I’ve even gone so far as taking Portuguese lessons to truly understand their spirit, and perhaps even hers a little bit. It had always been my intention to write to Amy at her home in Rio and let her know how grateful I am for the gift she bestowed upon me that somehow gets bigger and more important as time progresses. Obrigado minha professora.

GAYLORD FIELDS, radio host.

In the ‘80s, when I was publicist for Concord Jazz Records, Amy was the music writer for the Christian Science Monitor. I sent her press releases and promo records and spoke to her by phone several times. In 2013 I took a trip to Rio and looked forward to finally meeting her. It was Halloween and she mentioned she missed candy corn and couldn’t find it in Brazil. I packed several packages to surprise her with. But every time we talked she came up with some reason we could not meet. We never did and I ate the candy corn on the plane trip home.

MERRILEE TROST, jazz publicist.

I did not know Amy. We had several lovely musical conversations on Facebook and I would have been proud to meet her. She seemed like a great musician and person, very genuine.

MARK CHRISTIAN MILLER, jazz vocalist.

My best remembrance of Amy is on Facebook in the recent past. We had wonderful conversations about family, especially Bertie, times at Gramma’s cottage in Dresden and past times. We connected as friends and family on FB. I am grateful for that.

LIBBY UNWIN, cousin.

After so many years of not seeing or talking to her, I found her on Facebook and it was like we never lost touch. Amy was so gifted in so many ways, composing, writing, translating. and of course, music. We chatted almost every day about family and my silly projects and she always encouraged me.

KAREN BATES, cousin.

When Amy joined the staff of Jazz History Online in 2012, she had just quit her day job as a translator, and she seemed eager to write about jazz again. Because of the notoriously bad mail service in Brazil, all of the recordings she reviewed were sent by e-mail or digital download. We could never talk on the phone, so we conversed by e-mail and Facebook. I’m grateful for that now, because I can read all of our old correspondence, and remember our wonderful friendship and collaboration.

THOMAS CUNNIFFE, Jazz History Online.

Amy always thought of herself as an introvert. She explained her need for solitude in this poignant blog entry.

For the past couple of decades I’ve felt an increasing need to be alone—not all the time, of course, but quite a bit of it. I think it’s partly because I’m a writer and composer, but also because it’s just my nature. It doesn’t feel odd to me. I’m comfortable being a loner. Lately I’ve been noticing—mostly from articles and memes on Facebook—that introverts are “in.” The memes say things like, “Whew, that was close, I almost had to socialize,” “That feeling of dread that washes over you when the phone rings,” “Come, they said, it’ll be fun, they said,” “The Introvert Revolution,” and so on. It seems as though introverts have found their niche, but…Somehow I don’t feel like waving an introvert flag. Why should I label myself? Why should anyone? We’re all different after all, sometimes in subtle ways, but we’re certainly not as classifiable as these memes and some articles I’ve read on the subject would have us believe. I say, enjoy who you are. Explore who you are. Most of us are too busy to spend time with ourselves, but we need to make time. We’re here for a reason, and the more time we spend finding out about what it is that we’re here to do and why we are the way we are (and this is NOT selfish, I might add), the better off we’ll be. Then others can benefit from our gifts, too.

AMY DUNCAN, from Finally Getting Down to Brass Tacks, November 2, 2016.

My darling Amy, I don’t know much about music but you forever changed my nonchalance into an appreciation of it. You were at times lonely and incredibly sad but you could also be ecstatic and on top of the world. You found that beautiful harmony in music and forever searched for it in your life. You composed pieces out of nowhere which matched your ability to pull information out of the air. You lived a full life yet in the end chose solitude. At times you showered those with love and other times you loved deeply from afar. You searched high and low trying to unlock the mysteries of life. You loved life and at times it loved you back. Like the beautiful Brazilian carnivals you loved, you touched so many people. You were not a note in the fabric of life, you were an entire orchestra.

VENIA HILL, friend.

Amy’s health started to fail in the final years of her life. As a Christian Scientist, she did not go to doctors, so it’s highly possible that Amy never knew what disease was killing her. (One cousin has suggested that Amy had kidney issues). Although her apartment was exactly one block from the beach, she rarely went out. She stopped playing the piano and composing. She also lost trust in her friends. Vocalist Stephanie Crawford, who had known Amy for over two decades, was one friend who kept in touch. On June 2, 2018, she called Amy, but after a few minutes, a hoarse-voiced Amy said she was too weak to talk. They agreed to talk again in a few days, but Amy never answered the phone again. Stephanie contacted Madeleine, who called the apartment building where Amy lived, and asked the doorman to keep tabs on Amy. For the next two weeks, he heard movement inside Amy’s apartment. When those sounds stopped, the Brazilian consulate was contacted. On July 6, the police entered the apartment by force, and found Amy’s body. The coroner stated that the body was too decomposed to establish the exact date of death and the cause. After a prolonged battle, Amy’s remains were cremated and taken back to the US. Her ashes will be spread off the coast of Winthrop, Massachusetts, near the final resting places of her sister and brother-in-law.

After she passed away I felt so empty. I wished we had met in person and I wanted to know more about her. She had changed, in my mind, from someone carefree and open to someone with secrets. I remembered that she had raved about a Bay Area vocalist, Stephanie Crawford, and urged me to go hear her. So, after Amy’s death, I contacted Stephanie and asked her to have lunch. I found they had been roommates in New York and I learned much more. She told me that Amy had been quite ill for the last few years but did not want others to know. She said Amy had become quite reclusive. I felt so bad. I wished I had known so I could have offered comfort and help. I wished I had told her that I loved her and how much our friendship meant to me. Amy Hildreth Duncan was the best friend I never met.

MERRILEE TROST, jazz publicist.

My mother’s death was difficult, but now I choose to remember all of the good stuff. In fact, I was doubled over laughing with my sister today remembering how incredibly funny she was. She had a wonderful silly streak and because she was so smart, her humor hit all the right notes all the time. But it wasn’t just her humor that stood out. Because she decided to follow her dreams of being a jazz musician against the wishes of her mother, she understood the importance of allowing my sister and I to follow our passions too. As a result, we both run successful small businesses always with the encouragement of our mother. After her death, I was talking with one of her very best friends, and she said that my mother’s shining quality was her compassion and support for those who needed it most. I love that.

MADELEINE MENDONCA, Amy’s eldest daughter.

Amy was a very talented musician. She also collaborated with and encouraged other musicians to express their talents as well. I love being part of her family, and I miss her a lot.

HAMILTON MENDONCA, Madeleine’s husband.

Amy Duncan

a true, enduring, abiding friend

a real pal

a buddy

a confidante

a heartbeat

a keeper of secrets

giving, unfailingly, unstintingly generous,

patient beyond reason or logic, sharp as a tack,

hip to the point of goofiness, kind, smart, practical, boundlessly patient,

extraordinarily intelligent, musical beyond description

wise as the stars

a magician, a visionary,

the bringer of joy

the love of my life

STEPHANIE CRAWFORD, vocalist and poet.

Thanks to all of the contributors, especially Amy’s AMAZING family!

Clippings from the Greeley Tribune provided by Katalyn Lutkin and Leonore Harriman of the City of Greeley Museums Hazel E. Johnson Research Center. Thanks to Louis Amestoy of the Tribune for allowing Jazz History Online to reprint Amy’s words here.

Family photos courtesy Hilary Alexander, Madeleine Mendonca and Molly Renda.

Cover photo by Robert Serbinenko.

We’re gonna miss you, Amy!