ALEX BAIRD: “LEMON TREE” (Next 42004)

I first became aware of Alex Baird in 2017 from her lyricized version of Hank Mobley’s “This I Dig of You”, posted as a YouTube video. That piece had always seemed ripe for words, but the energy required to sing Mobley’s leaping 5-chorus solo might have steered other vocalists away. But youth knows no boundaries, and Baird uses this vehicle (retitled “It’s You I Dig”) as the lead-off track of her debut album, “Lemon Tree”. Although the tempo is a little slower than the original video (where she sang with Mobley’s recording), Baird infuses this piece with boundless energy and unrestrained joy. With a voice reminiscent of Stacey Kent, Baird sings with exceptional diction—even on the rapid vocalese lyrics—and she generates a distinctive personality. Baird’s talent extends far beyond vocalese, proven with the next two tracks, “All I Needed” an original soul-soaked ballad about a doomed relationship, and “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered”, where Larry Hart’s lyrics approach the same subject from a different angle. Here, Baird adjusts her vocal timbre to meet the needs of the words. The title track offers a stunning summation of her jazz chops, starting with the delightful original composition, and continuing through a well-crafted scat solo and a fine ensemble chorus. “Don’t Let Me Lose My Way” is another powerful love song with overdubbed background vocals over the turbulent rhythm of Darrell Grant (keyboards), Lucas Winter (guitar), Clark Sommers (bass), and Mark Ferber (drums). “Save Your Love for Me” is an exhilarating cover of the Nancy Wilson/Cannonball Adderley recording, with the surging rhythm highlighted by Grant, who doubles on Rhodes and organ. Baird comes from a fine lineage—her grandmother was Peggi Griffith, a jazz singer who sang in Washington state in the 1950s and early 1960s—and she has included two of Griffith’s originals on this album. Both “You’re in My Arms to Stay” and “As Long as You Want Me” are performed with great verve and enthusiasm, with Thomas Marriott’s trumpet adding superb obbligati. Although Baird wrote the songs “Never to Be Yours” and “Connection” five years apart, they seem to describe the transition between old and new loves. To close the album, Baird couples two pieces created in 1976, “It’s No Time to Be Blue”—based on Dexter Gordon’s solo on “Blue Bossa”—and “Still Crazy After All These Years”—with a Paul Simon lyric packed with hidden meanings. “Lemon Tree” reveals many aspects of Alex Baird’s abundant gifts. She may have a great career ahead. She captured me with the first tune.

I first became aware of Alex Baird in 2017 from her lyricized version of Hank Mobley’s “This I Dig of You”, posted as a YouTube video. That piece had always seemed ripe for words, but the energy required to sing Mobley’s leaping 5-chorus solo might have steered other vocalists away. But youth knows no boundaries, and Baird uses this vehicle (retitled “It’s You I Dig”) as the lead-off track of her debut album, “Lemon Tree”. Although the tempo is a little slower than the original video (where she sang with Mobley’s recording), Baird infuses this piece with boundless energy and unrestrained joy. With a voice reminiscent of Stacey Kent, Baird sings with exceptional diction—even on the rapid vocalese lyrics—and she generates a distinctive personality. Baird’s talent extends far beyond vocalese, proven with the next two tracks, “All I Needed” an original soul-soaked ballad about a doomed relationship, and “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered”, where Larry Hart’s lyrics approach the same subject from a different angle. Here, Baird adjusts her vocal timbre to meet the needs of the words. The title track offers a stunning summation of her jazz chops, starting with the delightful original composition, and continuing through a well-crafted scat solo and a fine ensemble chorus. “Don’t Let Me Lose My Way” is another powerful love song with overdubbed background vocals over the turbulent rhythm of Darrell Grant (keyboards), Lucas Winter (guitar), Clark Sommers (bass), and Mark Ferber (drums). “Save Your Love for Me” is an exhilarating cover of the Nancy Wilson/Cannonball Adderley recording, with the surging rhythm highlighted by Grant, who doubles on Rhodes and organ. Baird comes from a fine lineage—her grandmother was Peggi Griffith, a jazz singer who sang in Washington state in the 1950s and early 1960s—and she has included two of Griffith’s originals on this album. Both “You’re in My Arms to Stay” and “As Long as You Want Me” are performed with great verve and enthusiasm, with Thomas Marriott’s trumpet adding superb obbligati. Although Baird wrote the songs “Never to Be Yours” and “Connection” five years apart, they seem to describe the transition between old and new loves. To close the album, Baird couples two pieces created in 1976, “It’s No Time to Be Blue”—based on Dexter Gordon’s solo on “Blue Bossa”—and “Still Crazy After All These Years”—with a Paul Simon lyric packed with hidden meanings. “Lemon Tree” reveals many aspects of Alex Baird’s abundant gifts. She may have a great career ahead. She captured me with the first tune.

DAWN DEROW: “MY SHIP” (Zoho 202111)

1941 was a pivotal year in American history, with the country on the edge of joining World War II. The songs of that year reflected the general mood with odes to lost lovers (“Lover Man”, “I Got it Bad”, “Blues in the Night”), simple pleasures (“Just Squeeze Me”, “Baby Mine”, “White Christmas”) and escapism (“My Ship”, “Skylark”, “How About You”). In her new CD “My Ship”, Dawn Derow reprises a highly-acclaimed nightclub show which highlights the above songs (with a few additions from the surrounding years). She imbues these familiar standards with an earnest, heartfelt delivery while discovering new ways to interpret the lyrics (“Chattanooga Choo Choo” may never be the same!). Derow is not a pure jazz singer, but she has listened and learned well. The Duke Ellington medley includes lovely examples of simple melodic variations and an admirable elasticity in phrasing. She lets the words flow behind the beat on “White Christmas” (and she also includes the rarely heard verse). Ian Herman leads the expanded orchestra from the keyboard, with Benny Benack III (trumpet), Dan Levine (trombone), and Aaron Heick (reeds) joining the rhythm section of Sean Harkness (guitar), Tom Hubbard (bass), and Daniel Glass (drums) and a string quintet. The arrangements by Herman and Barry Levitt are fresh and creative, using the words as pivot points (hear the delightful setting of “The Ballad of Jenny” for particularly good examples). The title track is the album’s highlight, as Derow’s heartfelt vocal is matched with an arrangement packed with wondrous orchestral colors. “The White Cliffs of Dover” is unabashedly sentimental, with Derow adopting a Broadway voice (complete with ramped-up vibrato) as a push to the grand finale. Unfortunately, it is one of the places where the performer’s emotions overwhelm the song. Derow has abundant talent, but if she wants to join the crowded world of jazz vocalists, she must learn the cardinal rule, “less is more”.

edge of joining World War II. The songs of that year reflected the general mood with odes to lost lovers (“Lover Man”, “I Got it Bad”, “Blues in the Night”), simple pleasures (“Just Squeeze Me”, “Baby Mine”, “White Christmas”) and escapism (“My Ship”, “Skylark”, “How About You”). In her new CD “My Ship”, Dawn Derow reprises a highly-acclaimed nightclub show which highlights the above songs (with a few additions from the surrounding years). She imbues these familiar standards with an earnest, heartfelt delivery while discovering new ways to interpret the lyrics (“Chattanooga Choo Choo” may never be the same!). Derow is not a pure jazz singer, but she has listened and learned well. The Duke Ellington medley includes lovely examples of simple melodic variations and an admirable elasticity in phrasing. She lets the words flow behind the beat on “White Christmas” (and she also includes the rarely heard verse). Ian Herman leads the expanded orchestra from the keyboard, with Benny Benack III (trumpet), Dan Levine (trombone), and Aaron Heick (reeds) joining the rhythm section of Sean Harkness (guitar), Tom Hubbard (bass), and Daniel Glass (drums) and a string quintet. The arrangements by Herman and Barry Levitt are fresh and creative, using the words as pivot points (hear the delightful setting of “The Ballad of Jenny” for particularly good examples). The title track is the album’s highlight, as Derow’s heartfelt vocal is matched with an arrangement packed with wondrous orchestral colors. “The White Cliffs of Dover” is unabashedly sentimental, with Derow adopting a Broadway voice (complete with ramped-up vibrato) as a push to the grand finale. Unfortunately, it is one of the places where the performer’s emotions overwhelm the song. Derow has abundant talent, but if she wants to join the crowded world of jazz vocalists, she must learn the cardinal rule, “less is more”.

CAROL SLOANE: “LIVE AT BIRDLAND” (Club 44 4122)

While Carol Sloane recorded many fine studio albums in her career, she always seemed more at ease when recording live. Her 1962 Columbia LP, “Live at 30th Street” set the tone through her confident performance of a well-chosen repertoire (her relaxed stage manner was not heard, but described in Peter Bogdanovich’s liner notes). Her easy communication with tenor saxophonist Ben Webster is evident throughout the splendid album, “Carol and Ben”, and she mesmerizes the audience on her rare and wonderful LP, “Subway Tokens”. “Live at Birdland” is the latest entry into Sloane’s live discography, and it may well be her last recording, as she is presently in failing health. If it is indeed her swan song, this recital from September 2019 is a grand exit. The album appears to capture an entire set, complete with stage announcements, extended introductions, and—in one case—a head arrangement expanded on the spot because Sloane and the musicians were having so much fun performing it. To be honest, Sloane’s voice was not in perfect condition—after all, she was in her early 80s then—but if there are minor problems with intonation and missed notes, it should not obscure Sloane’s stunning interpretive skills. She makes us believe the sentiments of Frank Loesser’s wartime song, “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You”, and then pares down Harold Arlen’s “As Long as I Live” with a rhythmically precise distillation of the melody bringing out the humorous lyrics. She couples two great standards “Glad to Be Unhappy” and “I’ve Got a Right to Sing the Blues” to reveal similar themes in the words. Sloane’s voice still had the honey-and-scotch flavor that marked her earlier albums, and her tender reading of “If I Should Lose You” was a perfect match for her sound. Sloane’s long-time friend and favored pianist Mike Renzi plays a perfect accompaniment, just enough to support Sloane, but not enough to upset the delicate balance between voice and piano (Renzi passed away during the pandemic, and his loss is particularly acute in light of this recording). Sloane’s other accompanists, tenor saxophonist Scott Hamilton and bassist Jay Leonhart return on the next tune, “You Were Meant for Me”, each performing swinging, well-constructed solos. Sloane was obviously inspired, adding a mixture of light scat and melodic variations in the final chorus. A tender rendition of “The Very Thought of You” opens with Sloane’s flawless reading of the verse, and the loose jam on “You’re Driving Me Crazy” takes several unexpected turns before finding its conclusion. Sloane prefaces her glorious rendition of “Two for the Road” by citing George Shearing’s vocal from his duet album with Carmen McRae. I concur with the recommendation, but add that Sloane now gives Shearing serious competition. A sunny take on “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” sets up the poignant finale, “I’ll Always Leave the Door a Little Open”. While the lyrics of the latter song make me miss Carol Sloane prematurely, I’m grateful that she has a rich legacy of recordings that will live on for many years to come.

While Carol Sloane recorded many fine studio albums in her career, she always seemed more at ease when recording live. Her 1962 Columbia LP, “Live at 30th Street” set the tone through her confident performance of a well-chosen repertoire (her relaxed stage manner was not heard, but described in Peter Bogdanovich’s liner notes). Her easy communication with tenor saxophonist Ben Webster is evident throughout the splendid album, “Carol and Ben”, and she mesmerizes the audience on her rare and wonderful LP, “Subway Tokens”. “Live at Birdland” is the latest entry into Sloane’s live discography, and it may well be her last recording, as she is presently in failing health. If it is indeed her swan song, this recital from September 2019 is a grand exit. The album appears to capture an entire set, complete with stage announcements, extended introductions, and—in one case—a head arrangement expanded on the spot because Sloane and the musicians were having so much fun performing it. To be honest, Sloane’s voice was not in perfect condition—after all, she was in her early 80s then—but if there are minor problems with intonation and missed notes, it should not obscure Sloane’s stunning interpretive skills. She makes us believe the sentiments of Frank Loesser’s wartime song, “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You”, and then pares down Harold Arlen’s “As Long as I Live” with a rhythmically precise distillation of the melody bringing out the humorous lyrics. She couples two great standards “Glad to Be Unhappy” and “I’ve Got a Right to Sing the Blues” to reveal similar themes in the words. Sloane’s voice still had the honey-and-scotch flavor that marked her earlier albums, and her tender reading of “If I Should Lose You” was a perfect match for her sound. Sloane’s long-time friend and favored pianist Mike Renzi plays a perfect accompaniment, just enough to support Sloane, but not enough to upset the delicate balance between voice and piano (Renzi passed away during the pandemic, and his loss is particularly acute in light of this recording). Sloane’s other accompanists, tenor saxophonist Scott Hamilton and bassist Jay Leonhart return on the next tune, “You Were Meant for Me”, each performing swinging, well-constructed solos. Sloane was obviously inspired, adding a mixture of light scat and melodic variations in the final chorus. A tender rendition of “The Very Thought of You” opens with Sloane’s flawless reading of the verse, and the loose jam on “You’re Driving Me Crazy” takes several unexpected turns before finding its conclusion. Sloane prefaces her glorious rendition of “Two for the Road” by citing George Shearing’s vocal from his duet album with Carmen McRae. I concur with the recommendation, but add that Sloane now gives Shearing serious competition. A sunny take on “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” sets up the poignant finale, “I’ll Always Leave the Door a Little Open”. While the lyrics of the latter song make me miss Carol Sloane prematurely, I’m grateful that she has a rich legacy of recordings that will live on for many years to come.

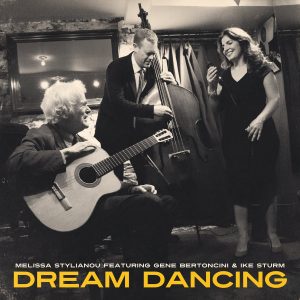

MELISSA STYLIANOU: “DREAM DANCING” (Anzic 80)

As one-third of the group Duchess, Melissa Stylianou shares a common trait with the other members of the group: a love of great classic songs. Stylianou’s new album, “Dream Dancing” features a finely-curated song list that mixes standards, jazz classics, and Brazilian perennials. Accompanied by two of her favorite musicians, guitarist Gene Bertoncini and bassist Ike Sturm, the close-miked recording feels more like an intimate conversation than a studio album. The interplay between guitar and bass locks in from the downbeat of the opener “Sweet and Lovely”. Stylianou’s final chorus finds her creating astounding variations on the melody, followed by a challenging unison passage with Bertoncini. On “If You Never Come to Me” (aka “Useless Landscape”) Stylianou invokes the saudade feeling which permeated Tom Jobim’s music, while Bertoncini and Sturm find creative ways to imply the bossa nova beat. “My Ideal”, a simple song with a profound lyric, is sung to perfection, complete with an unexpected but highly appropriate interpolation. Sturm provides a strong walking bass on an adventurous take on “It Could Happen to You”, which is followed by Bertoncini’s wordless memorial “For Chet”. The latter piece may not be reminiscent of Baker, but the performance is understated and memorable. A swinging medium-tempo version of “Perdido” features a Stylianou scat solo, which is admirably spare and marked by fine note choices. “Corcovado” is first sung in Portuguese, followed by a simultaneous distillation of the English lyric and the original melody. On the recapitulation, Bertoncini provides a splendid accompaniment to Stylianou’s reprise of the Portuguese lyric. “Times A-Wastin’” (better known as “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be”) utilizes Don George’s hipster lyrics and an equally hip vocal improvisation. “My One and Only Love” is offered as a voice/guitar duet, and the two principals effortlessly stretch and retract the time as they interpret this lovely song. Bertoncini introduces “It Might as Well Be Spring” with a quote from another Spring song, and the backing for the opening chorus reflects the uneasy similes of the lyric. Stylianou takes audacious chances in the final chorus, but they are flawlessly executed. Just like the rest of this delightful album.

As one-third of the group Duchess, Melissa Stylianou shares a common trait with the other members of the group: a love of great classic songs. Stylianou’s new album, “Dream Dancing” features a finely-curated song list that mixes standards, jazz classics, and Brazilian perennials. Accompanied by two of her favorite musicians, guitarist Gene Bertoncini and bassist Ike Sturm, the close-miked recording feels more like an intimate conversation than a studio album. The interplay between guitar and bass locks in from the downbeat of the opener “Sweet and Lovely”. Stylianou’s final chorus finds her creating astounding variations on the melody, followed by a challenging unison passage with Bertoncini. On “If You Never Come to Me” (aka “Useless Landscape”) Stylianou invokes the saudade feeling which permeated Tom Jobim’s music, while Bertoncini and Sturm find creative ways to imply the bossa nova beat. “My Ideal”, a simple song with a profound lyric, is sung to perfection, complete with an unexpected but highly appropriate interpolation. Sturm provides a strong walking bass on an adventurous take on “It Could Happen to You”, which is followed by Bertoncini’s wordless memorial “For Chet”. The latter piece may not be reminiscent of Baker, but the performance is understated and memorable. A swinging medium-tempo version of “Perdido” features a Stylianou scat solo, which is admirably spare and marked by fine note choices. “Corcovado” is first sung in Portuguese, followed by a simultaneous distillation of the English lyric and the original melody. On the recapitulation, Bertoncini provides a splendid accompaniment to Stylianou’s reprise of the Portuguese lyric. “Times A-Wastin’” (better known as “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be”) utilizes Don George’s hipster lyrics and an equally hip vocal improvisation. “My One and Only Love” is offered as a voice/guitar duet, and the two principals effortlessly stretch and retract the time as they interpret this lovely song. Bertoncini introduces “It Might as Well Be Spring” with a quote from another Spring song, and the backing for the opening chorus reflects the uneasy similes of the lyric. Stylianou takes audacious chances in the final chorus, but they are flawlessly executed. Just like the rest of this delightful album.

TIERNEY SUTTON: “PARIS SESSIONS 2” (BFM 834 679)

The title of Tierney Sutton’s new CD is something of a misnomer. While the first volume of “Paris Sessions” was indeed recorded in France, the sequel “Paris Sessions 2” was recorded in Glendale, California during the pandemic. However, the new album is clearly a continuation of the earlier album uniting Sutton with guitarist Serge Merlaud and bassist Kevin Axt. Sutton opens “Triste” alone scatting a felicitous riff which is later developed into a full chorus passage for voice and bass. She sings the song in Portuguese before Merlaud performs a tasty single-string solo, and then Sutton alternates between scat and Portuguese for the rest of the track. Next comes a medley of songs set in the City of Light with Vernon Duke’s “April in Paris” leading into Joni Mitchell’s “Free Man in Paris”. The two songs alternate through the track rather than being played one after the other. This juxtaposition exposes the contrasting viewpoints of the lyrics. Hubert Laws makes his first appearance on Jobim’s “Zingaro” as he performs a rubato duet with Sutton. Laws recorded all of his parts remotely, so the precise synchronization of flute and voice is particularly remarkable. Technology aside, it is a breathtaking rendition of an underappreciated Jobim standard. A slow and wistful “Isn’t it a Pity” allows us to savor Ira Gershwin’s thoughtful lyrics, while “Beautiful Love” starts out sounding like an art song for voice and guitar, but Axt enters with the bass riff from Chick Corea’s “Sea Journey” and that transforms the entire mood. The album is dedicated to the late Marilyn Bergman, and Sutton includes three lovely songs with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman: “I Knew I Loved You” (from “Cinema Paradiso”), “Moonlight” (from “Sabrina”), and “A Child is Born” (composed by Dave Grusin, not Thad Jones). Sutton’s interpretations provide deep insights into the words and music. A tender exploration of “Pure Imagination” acts as a tribute to Leslie Bricusse, who passed away between the recording session and the album’s release. The bossa nova returns to the program with a breezy version of “Doralice” where Dorival Caymmi’s melody segues directly into a unison passage for guitar and voice. Sutton continues her ongoing exploration of Sting’s music with a touching version of “August Winds” before moving to Cole Porter for a sexy rendition of “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To”. The album’s closer, “Chorado” features another telepathic rubato duet between Sutton and Laws, with spare accompaniment from Merlaud, and a few delicate vocal overdubs. This album is a piece of rare beauty; treasure it in these troubled times.

The title of Tierney Sutton’s new CD is something of a misnomer. While the first volume of “Paris Sessions” was indeed recorded in France, the sequel “Paris Sessions 2” was recorded in Glendale, California during the pandemic. However, the new album is clearly a continuation of the earlier album uniting Sutton with guitarist Serge Merlaud and bassist Kevin Axt. Sutton opens “Triste” alone scatting a felicitous riff which is later developed into a full chorus passage for voice and bass. She sings the song in Portuguese before Merlaud performs a tasty single-string solo, and then Sutton alternates between scat and Portuguese for the rest of the track. Next comes a medley of songs set in the City of Light with Vernon Duke’s “April in Paris” leading into Joni Mitchell’s “Free Man in Paris”. The two songs alternate through the track rather than being played one after the other. This juxtaposition exposes the contrasting viewpoints of the lyrics. Hubert Laws makes his first appearance on Jobim’s “Zingaro” as he performs a rubato duet with Sutton. Laws recorded all of his parts remotely, so the precise synchronization of flute and voice is particularly remarkable. Technology aside, it is a breathtaking rendition of an underappreciated Jobim standard. A slow and wistful “Isn’t it a Pity” allows us to savor Ira Gershwin’s thoughtful lyrics, while “Beautiful Love” starts out sounding like an art song for voice and guitar, but Axt enters with the bass riff from Chick Corea’s “Sea Journey” and that transforms the entire mood. The album is dedicated to the late Marilyn Bergman, and Sutton includes three lovely songs with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman: “I Knew I Loved You” (from “Cinema Paradiso”), “Moonlight” (from “Sabrina”), and “A Child is Born” (composed by Dave Grusin, not Thad Jones). Sutton’s interpretations provide deep insights into the words and music. A tender exploration of “Pure Imagination” acts as a tribute to Leslie Bricusse, who passed away between the recording session and the album’s release. The bossa nova returns to the program with a breezy version of “Doralice” where Dorival Caymmi’s melody segues directly into a unison passage for guitar and voice. Sutton continues her ongoing exploration of Sting’s music with a touching version of “August Winds” before moving to Cole Porter for a sexy rendition of “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To”. The album’s closer, “Chorado” features another telepathic rubato duet between Sutton and Laws, with spare accompaniment from Merlaud, and a few delicate vocal overdubs. This album is a piece of rare beauty; treasure it in these troubled times.

MARK WINKLER: “LATE BLOOMIN’ JAZZMAN” (Café Pacific 6010)

The songs on Mark Winkler’s new CD, “Late Bloomin’ Jazzman” sound like a valedictorian recital, but from the energy he projects throughout the disc, I don’t believe he’s ready to retire quite yet. He swaggers through a hip version of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” and digs into the shuffle beat on “Don’t Be Blue” as a prelude to the album’s main purpose: the definitive performances of eight pieces featuring Winkler’s lyrics. “When All the Lights in the Sign Worked” was inspired by film noir, and it comes with a femme fatale and knowing references to Stan Kenton and Duke Ellington. The title track chides the jazz fans who ignore the veteran players in favor of the young lions. It’s too bad that Mark Murphy didn’t get the chance to perform this song, but Winkler personifies the aging hipster who knows which musicians play the most profound music. “In Another Way” is a poignant tale about the transition between a lost love and a new partner. “Bossa Nova Days” romances the heyday of Jobim, Gilberto, and Bonfá. Bob Sheppard’s tenor sax evokes Stan Getz, and Grant Geissman’s guitar memorializes Roberto Menescal. “Old Devil Moon” was inspired by Bob Dorough’s recording, and the band—featuring Brian Swartz (trumpet), Sheppard (tenor), Rich Eames (piano), Geissman (guitar), Gabe Davis (bass), and Christian Euman (drums)—propels Winkler’s swinging delivery. [Other notable instrumentalists include David Benoit, Jon Mayer, and Jamieson Trotter (piano); John Clayton (bass), and Clayton Cameron (drums)]. The Lorraine Feather/Shelly Berg love song “I Always Had a Thing for You” presents a contrasting style to the next four Winkler originals, which all deal with aging and loss. “Before You Leave” portrays an all-too-familiar scene from relationships, while “Old Enough,” tells of the disillusionment when we discover the true lessons of life. “Marlena’s Memories” is a heartbreaking song about a woman dying from Alzheimer’s disease. The realism of these lyrics will affect anyone who has lost someone to this terrible disease. The album comes full circle with “If Gershwin Had Lived”, a wry speculation that could be applied to any artist who died young. I trust that Winkler will continue to record and perform. I suspect that he has much more to give.

The songs on Mark Winkler’s new CD, “Late Bloomin’ Jazzman” sound like a valedictorian recital, but from the energy he projects throughout the disc, I don’t believe he’s ready to retire quite yet. He swaggers through a hip version of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” and digs into the shuffle beat on “Don’t Be Blue” as a prelude to the album’s main purpose: the definitive performances of eight pieces featuring Winkler’s lyrics. “When All the Lights in the Sign Worked” was inspired by film noir, and it comes with a femme fatale and knowing references to Stan Kenton and Duke Ellington. The title track chides the jazz fans who ignore the veteran players in favor of the young lions. It’s too bad that Mark Murphy didn’t get the chance to perform this song, but Winkler personifies the aging hipster who knows which musicians play the most profound music. “In Another Way” is a poignant tale about the transition between a lost love and a new partner. “Bossa Nova Days” romances the heyday of Jobim, Gilberto, and Bonfá. Bob Sheppard’s tenor sax evokes Stan Getz, and Grant Geissman’s guitar memorializes Roberto Menescal. “Old Devil Moon” was inspired by Bob Dorough’s recording, and the band—featuring Brian Swartz (trumpet), Sheppard (tenor), Rich Eames (piano), Geissman (guitar), Gabe Davis (bass), and Christian Euman (drums)—propels Winkler’s swinging delivery. [Other notable instrumentalists include David Benoit, Jon Mayer, and Jamieson Trotter (piano); John Clayton (bass), and Clayton Cameron (drums)]. The Lorraine Feather/Shelly Berg love song “I Always Had a Thing for You” presents a contrasting style to the next four Winkler originals, which all deal with aging and loss. “Before You Leave” portrays an all-too-familiar scene from relationships, while “Old Enough,” tells of the disillusionment when we discover the true lessons of life. “Marlena’s Memories” is a heartbreaking song about a woman dying from Alzheimer’s disease. The realism of these lyrics will affect anyone who has lost someone to this terrible disease. The album comes full circle with “If Gershwin Had Lived”, a wry speculation that could be applied to any artist who died young. I trust that Winkler will continue to record and perform. I suspect that he has much more to give.