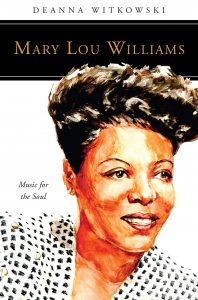

For over two decades, pianist and author Deanna Witkowski has immersed herself in the life, music, and world of Mary Lou Williams. Her dedication has led her to move to Williams’ adopted hometown of Pittsburgh, arrange, publish and record her music, and even convert to Catholicism. In her new book on Williams’ life, “Music for the Soul” (Liturgical Press), she writes of seeing images of Williams all across Pittsburgh, finding old friends and relatives in Williams’ former neighborhoods, and discovering Williams’ cigarette-stained Baldwin piano at  a local museum. An outstanding pianist in her own right, Witkowski has recently released an album-length tribute to Williams, “Force of Nature” (MCG Jazz 1055) which offers accurate transcriptions of Williams’ originals juxtaposed with superb improvisations exploring the depth of those works. Clearly, Witkowski knows her subject very well!

a local museum. An outstanding pianist in her own right, Witkowski has recently released an album-length tribute to Williams, “Force of Nature” (MCG Jazz 1055) which offers accurate transcriptions of Williams’ originals juxtaposed with superb improvisations exploring the depth of those works. Clearly, Witkowski knows her subject very well!

I’ve resisted the urge to call Witkowski’s book a biography for several reasons. The book’s modest length is a good place to start. Compared to the 300–500 page biographies of Williams by Linda Dahl and Tammy Kernodle, Witkowski’s 127-page should not be expected to include the same level of detail. In fact, it only does so for the last three-quarters of its length.  The scope of Witkowski’s monograph—Williams’ conversion to Catholicism with special emphasis on her sacred music—is consistent with the concept of a “spiritual biography”. This text was originally conceived as an expanded study of Williams’ later years and the first half of the book (which sketches Williams’ pre-Church life) was added at the publisher’s insistence to increase its accessibility for those unfamiliar with Williams’ life story.

The scope of Witkowski’s monograph—Williams’ conversion to Catholicism with special emphasis on her sacred music—is consistent with the concept of a “spiritual biography”. This text was originally conceived as an expanded study of Williams’ later years and the first half of the book (which sketches Williams’ pre-Church life) was added at the publisher’s insistence to increase its accessibility for those unfamiliar with Williams’ life story.

The writing style reveals the approach. Witkowski condenses the first 44 years of Williams’ life into just 41 pages of text. Think about that: her education, early performing experiences, rise as both pianist and arranger in the Andy Kirk Clouds of Joy, recordings, success in New York, the salons with rising jazz musicians, and her first trip overseas, all in 41 pages. Admittedly, there are some details—but so much is not there: her relationships with Jack Teagarden and David Stone Martin, discussions of her recordings, and her groundbreaking big band arrangements for Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington (“Trumpets No End” doesn’t even get a mention!), and the adaptation of her basic style to accommodate the newer forms of jazz. The last point is particularly essential: Mary Lou Williams was one of the few jazz musicians with direct experience playing multiple genres. Understanding that part of Williams’ art is crucial to understanding her unique stature in the music. In addition, there are a few sloppy mistakes. The narrative strongly implies that Lester Young and Charlie Parker were active players in Kansas City when Williams first arrived there in 1928. In fact, Young didn’t arrive in town for another 5 years, and Parker was 3 years away from getting his first saxophone. Witkowski also misassigns Dave Brubeck as part of the cool jazz movement and opens the worm-can regarding the authorship of the tune known under the titles “Rifftide” and “Hackensack”.

However, from the point where Williams converts, the writing and research are immaculate. Witkowski accurately depicts the atmosphere of the time period, contrasts Williams’ sacred music with the other jazz and folk settings of the mass from the time, and meticulously traces Williams’ interactions with priests, sponsors, and musicians as she tries to help her fellow jazz musicians, and survive on her own. The rise and fall of her Bel Canto charitable organization is discussed without laying judgment on Williams for her sometimes naïve approach. It is in this critical section that Witkowski’s immersion in her subject is most apparent. She seems to understand Williams’ motivations and impulses throughout the difficult odyssey of her final decades. Witkowski also discusses several of Williams’ late albums in non-technical language to speak to non-musicians. I’m surprised that she did not include Williams’ outstanding performance at the 1978 Montreux Jazz Festival or her neglected Pablo disc, “My Mama Pinned a Rose on Me”, but I’m grateful that at least some of her music was discussed.

After Williams’ stunning 9-minute solo performance at the 1978 White House Jazz Festival, an awestruck George Wein told the audience, “There’s a lot of musical knowledge involved in what that lady just did”. Similarly, there is great knowledge in what Witkowski has done. While “Music for the Soul” has earned several awards, it is not a full representation of Witkowski’s extensive knowledge of Mary Lou Williams. I hope that sometime in the coming years, she will return to this subject, and present an equally-compelling account of Mary Lou’s early life.