The COVID-19 has shut down the world’s economy in short order. While elements of the economy are beginning to open up again, live performances will be one of the last elements to restart. Most club and concert dates have been canceled for the foreseeable future. For many jazz artists, recorded music is their primary source of income. The albums reviewed here are all current releases; most of them were released during the period of nationwide lockdown. Of course, most of the music was recorded long before anyone had heard of the coronavirus. Many of these musicians are still producing music online, which is understandably different than these albums. However, these recordings show us what we as audience members took for granted before the virus. These reviews will be a continuing feature on Jazz History Online as long as the crisis continues. The current set encompasses instrumental jazz. JHO has always encouraged its readers to support the musicians by purchasing their CDs. The message could not be more urgent now. If you can afford to help, please do.

FRANCO AMBROSETTI: “LOST WITHIN YOU” (Unit 4970)

For the past few decades, Swiss trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti has made frequent trips to the United States to record with the best available New York musicians. His latest recording, “Lost Within You” was recorded weeks before the pandemic hit the US. It is primarily composed of standards—both American pop and jazz classics—with only two Ambrosetti originals included in the mix. True to form, Ambrosetti has picked an all-star lineup; here, he features John Scofield on guitar, Scott Colley on bass, Jack DeJohnette on drums, and two alternating pianists, Uri Caine and Renee Rosnes. However, the extended piano introduction to the opening track “Peace” is played by DeJohnette. Ambrosetti joins him on flugelhorn for an intimate duet before Scofield and Colley complete the ensemble. DeJohnette’s heartfelt piano solo is a notable contrast to the open, spacey style of his introduction. Surprisingly, DeJohnette does not return to his drum kit on the next track, “I’m Gonna Laugh You Right Out of My Life”, which is elegantly covered by flugelhorn, piano (Rosnes), and Colley. Rosnes provides subtle accompaniment to Ambrosetti’s fragile-but-fluid melody statement, and the subsequent improvisations by Rosnes and Colley provide answers to Ambrosetti’s melancholy solo. “Silli in the Sky” was originally written for a production of Harold Pinter’s “The Lovers” starring Ambrosetti’s wife, Silli. It’s hard to imagine this light and attractive bossa nova showing up in the middle of an intense Pinter scene, but the full ensemble (with Rosnes still on piano) lets the piece stand on its own. The opening chorus of “Love Like Ours” offers one of the album’s high points. Rosnes and Colley provide what sounds like a typical introduction, but then Colley drops out. There is a dramatic pause, Rosnes returns alone, and then Ambrosetti and Rosnes play a beautiful rubato half-chorus of the melody before Colley re-enters to establish the ballad tempo. The warmth and intensity of the track are a testament to the maturity and wisdom of all three musicians. Caine appears on the next three tracks, and his style makes an effective contrast to Rosnes as he leans into the keyboard with sharply defined chords and rhythmic patterns. His solo on Ambrosetti’s “Dreams of a Butterfly” sparkles over DeJohnette’s driving tom-tom patterns. Next comes the leader’s fourth recording of “Body and Soul”. DeJohnette starts the track with a brief, understated drum solo (!) before the band settles into a familiar ballad groove. The melody returns persistently throughout the first chorus, but Ambrosetti finally pulls away with a wondrous solo that forges new paths through the well-known chord progression. Benny Carter’s “People Time”—long associated with Stan Getz’s final recordings—yields a sensitive performance from the Ambrosetti/Caine/ Colley trio, while “Flamenco Sketches”—a late addition to the playlist—reveals how Ambrosetti and Rosnes continue to reflect and develop the music composed by Miles Davis and Bill Evans. DeJohnette (also a Davis alumni) adds his own enhancements of Jimmy Cobb’s original performance through dramatic cymbal hits and stirring tom-tom accents. The end result is a rendition that is respectful of the “Kind of Blue” version but far more dramatic than its earlier incarnations. This superb recital closes with a tender reading of McCoy Tyner’s ballad, “You Taught My Heart to Sing”. Sensitive listeners only need this lovely album to make their hearts sing.

made frequent trips to the United States to record with the best available New York musicians. His latest recording, “Lost Within You” was recorded weeks before the pandemic hit the US. It is primarily composed of standards—both American pop and jazz classics—with only two Ambrosetti originals included in the mix. True to form, Ambrosetti has picked an all-star lineup; here, he features John Scofield on guitar, Scott Colley on bass, Jack DeJohnette on drums, and two alternating pianists, Uri Caine and Renee Rosnes. However, the extended piano introduction to the opening track “Peace” is played by DeJohnette. Ambrosetti joins him on flugelhorn for an intimate duet before Scofield and Colley complete the ensemble. DeJohnette’s heartfelt piano solo is a notable contrast to the open, spacey style of his introduction. Surprisingly, DeJohnette does not return to his drum kit on the next track, “I’m Gonna Laugh You Right Out of My Life”, which is elegantly covered by flugelhorn, piano (Rosnes), and Colley. Rosnes provides subtle accompaniment to Ambrosetti’s fragile-but-fluid melody statement, and the subsequent improvisations by Rosnes and Colley provide answers to Ambrosetti’s melancholy solo. “Silli in the Sky” was originally written for a production of Harold Pinter’s “The Lovers” starring Ambrosetti’s wife, Silli. It’s hard to imagine this light and attractive bossa nova showing up in the middle of an intense Pinter scene, but the full ensemble (with Rosnes still on piano) lets the piece stand on its own. The opening chorus of “Love Like Ours” offers one of the album’s high points. Rosnes and Colley provide what sounds like a typical introduction, but then Colley drops out. There is a dramatic pause, Rosnes returns alone, and then Ambrosetti and Rosnes play a beautiful rubato half-chorus of the melody before Colley re-enters to establish the ballad tempo. The warmth and intensity of the track are a testament to the maturity and wisdom of all three musicians. Caine appears on the next three tracks, and his style makes an effective contrast to Rosnes as he leans into the keyboard with sharply defined chords and rhythmic patterns. His solo on Ambrosetti’s “Dreams of a Butterfly” sparkles over DeJohnette’s driving tom-tom patterns. Next comes the leader’s fourth recording of “Body and Soul”. DeJohnette starts the track with a brief, understated drum solo (!) before the band settles into a familiar ballad groove. The melody returns persistently throughout the first chorus, but Ambrosetti finally pulls away with a wondrous solo that forges new paths through the well-known chord progression. Benny Carter’s “People Time”—long associated with Stan Getz’s final recordings—yields a sensitive performance from the Ambrosetti/Caine/ Colley trio, while “Flamenco Sketches”—a late addition to the playlist—reveals how Ambrosetti and Rosnes continue to reflect and develop the music composed by Miles Davis and Bill Evans. DeJohnette (also a Davis alumni) adds his own enhancements of Jimmy Cobb’s original performance through dramatic cymbal hits and stirring tom-tom accents. The end result is a rendition that is respectful of the “Kind of Blue” version but far more dramatic than its earlier incarnations. This superb recital closes with a tender reading of McCoy Tyner’s ballad, “You Taught My Heart to Sing”. Sensitive listeners only need this lovely album to make their hearts sing.

JANE IRA BLOOM & MARK HELIAS: “SOME KIND OF TOMORROW” (download only)

It could be argued that “Some Kind of Tomorrow” is a direct reaction to the pandemic. It was recorded remotely during the lockdown with soprano saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom and bassist Mark Helias improvising together over a Wi-Fi connection. The two musicians had to work out difficulties with the technology before they could let their musical imaginations co-exist in the same time (if not physical) space. I have long admired Bloom’s rich tone on the soprano sax, but I don’t recall hearing it sound as melancholy as it does here. Making music is a communal effort and the sudden necessity of playing individual parts in solitude is a shock that reverberates with musicians every day. The audio mix of this recording makes us believe that Bloom and Helias were playing together in the same room; the fact that they couldn’t do that makes this album all the more remarkable. The opening (title) track finds both musicians in a highly melodic framework, but the next track, “Magic Carpet” takes them into exploratory areas, with Bloom and Helias altering the tones of their instruments through completely non-electronic means. Bloom’s Doppler effect—creating by swinging the bell of her horn across the arc of the microphone—and her deliberate coarsening of her tone are here along with Helias’ pizzicato and harmonics (A later track, “Drift”, has Bloom making her horn sound like an indigenous flute!) Bloom states in her program notes that none of these pieces were written out, and there were no discussions between her and Helias before they started playing. If we assume that these improvisations are presented in their complete form (and they certainly sound that way) then we must marvel at the speed at which moods are created and how well they are maintained for the length of the tracks. In the case of “Roughing It”—the album’s longest track—it is the manner and number of mood changes that occur as the improvisation evolves which stuns and delights the attentive listener. And indeed, it is the attentive listener who will get the most enjoyment from this album, as they share the same musical discoveries that struck Bloom and Helias when they created this music several months ago. Because of the circumstances of its creation, “Some Kind of Tomorrow” cannot offer the same sonic variety as Bloom’s earlier albums. In exchange, it gives us an unusually close perspective into her creativity and musicianship.

It could be argued that “Some Kind of Tomorrow” is a direct reaction to the pandemic. It was recorded remotely during the lockdown with soprano saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom and bassist Mark Helias improvising together over a Wi-Fi connection. The two musicians had to work out difficulties with the technology before they could let their musical imaginations co-exist in the same time (if not physical) space. I have long admired Bloom’s rich tone on the soprano sax, but I don’t recall hearing it sound as melancholy as it does here. Making music is a communal effort and the sudden necessity of playing individual parts in solitude is a shock that reverberates with musicians every day. The audio mix of this recording makes us believe that Bloom and Helias were playing together in the same room; the fact that they couldn’t do that makes this album all the more remarkable. The opening (title) track finds both musicians in a highly melodic framework, but the next track, “Magic Carpet” takes them into exploratory areas, with Bloom and Helias altering the tones of their instruments through completely non-electronic means. Bloom’s Doppler effect—creating by swinging the bell of her horn across the arc of the microphone—and her deliberate coarsening of her tone are here along with Helias’ pizzicato and harmonics (A later track, “Drift”, has Bloom making her horn sound like an indigenous flute!) Bloom states in her program notes that none of these pieces were written out, and there were no discussions between her and Helias before they started playing. If we assume that these improvisations are presented in their complete form (and they certainly sound that way) then we must marvel at the speed at which moods are created and how well they are maintained for the length of the tracks. In the case of “Roughing It”—the album’s longest track—it is the manner and number of mood changes that occur as the improvisation evolves which stuns and delights the attentive listener. And indeed, it is the attentive listener who will get the most enjoyment from this album, as they share the same musical discoveries that struck Bloom and Helias when they created this music several months ago. Because of the circumstances of its creation, “Some Kind of Tomorrow” cannot offer the same sonic variety as Bloom’s earlier albums. In exchange, it gives us an unusually close perspective into her creativity and musicianship.

NOAH HAIDU: “SLOWLY: SONG FOR KEITH JARRETT” (Sunnyside 1596)

Since the peak of the pandemic, the New York Times has run an occasional column titled “Those We’ve Lost”, spotlighting community members who had died from COVID-19. Losses come in many forms, though, and in addition to those musicians who were also COVID victims, the jazz world has lost the voice of a master musician who is still living at press time: Keith Jarrett. As pianist Noah Haidu was preparing to record with bassist Buster Williams and drummer Billy Hart in October 2020, Jarrett told the world that he had experienced two strokes which left him partially paralyzed and unable to perform in public anymore. “Slowly: Song for Keith Jarrett”, then, is that rarity among tribute albums, a recording that the subject will actually be able to hear and appreciate while still on the planet. The focus is on Jarrett’s “Standards” trio (with Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette) but the Haidu/Williams/Hart trio presents a distinctive sound of their own. Haidu’s improvised solo lines flow above the beat, with the ends of phrases falling off like dying fireworks. Williams’ rich tone provides strong support without tying itself to the beat. Hart’s delicate and precise cymbal work is underscored with snare, tom-tom, and bass hits which always appear where they are needed and never where they are not. Each member of the group brought in originals for the date, and even if they weren’t written with Jarrett in mind, the group’s amazing cohesion makes us believe that these tunes belong here. And while Jarrett made recordings of the standards recorded on this album—“What a Difference a Day Makes”, “Georgia on My Mind”, and “But Beautiful”—it is not necessary to compare Haidu’s versions to Jarrett’s, for it is Jarrett’s spirit that appears in every bar of this music: the passionate lines, deep swing and yes, even a little of the “singing” along the way. Part of Haidu’s affinity for Jarrett comes through Haidu’s late father, who introduced him to jazz, hipped him to Jarrett’s “Köln Concert”, and then attended Jarrett concerts with him. Death took the father a week before Jarrett’s last New York concert appearance in February 2017. Yet it is not his father’s passing nor Jarrett’s inability to play that truly contributes to the success of this album. It is Haidu’s study and absorption of Jarrett’s style which allows him to interpret this music in the way Jarrett might have performed it. With the assistance of two sensitive and renowned musicians in the forms of Buster Williams and Billy Hart, as well as a fine production team (executive producer François Zalacain and engineer Chris Allen) this is an album that proclaims the legacy of Keith Jarrett without reducing to mimicry or hastily-arranged covers.

though, and in addition to those musicians who were also COVID victims, the jazz world has lost the voice of a master musician who is still living at press time: Keith Jarrett. As pianist Noah Haidu was preparing to record with bassist Buster Williams and drummer Billy Hart in October 2020, Jarrett told the world that he had experienced two strokes which left him partially paralyzed and unable to perform in public anymore. “Slowly: Song for Keith Jarrett”, then, is that rarity among tribute albums, a recording that the subject will actually be able to hear and appreciate while still on the planet. The focus is on Jarrett’s “Standards” trio (with Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette) but the Haidu/Williams/Hart trio presents a distinctive sound of their own. Haidu’s improvised solo lines flow above the beat, with the ends of phrases falling off like dying fireworks. Williams’ rich tone provides strong support without tying itself to the beat. Hart’s delicate and precise cymbal work is underscored with snare, tom-tom, and bass hits which always appear where they are needed and never where they are not. Each member of the group brought in originals for the date, and even if they weren’t written with Jarrett in mind, the group’s amazing cohesion makes us believe that these tunes belong here. And while Jarrett made recordings of the standards recorded on this album—“What a Difference a Day Makes”, “Georgia on My Mind”, and “But Beautiful”—it is not necessary to compare Haidu’s versions to Jarrett’s, for it is Jarrett’s spirit that appears in every bar of this music: the passionate lines, deep swing and yes, even a little of the “singing” along the way. Part of Haidu’s affinity for Jarrett comes through Haidu’s late father, who introduced him to jazz, hipped him to Jarrett’s “Köln Concert”, and then attended Jarrett concerts with him. Death took the father a week before Jarrett’s last New York concert appearance in February 2017. Yet it is not his father’s passing nor Jarrett’s inability to play that truly contributes to the success of this album. It is Haidu’s study and absorption of Jarrett’s style which allows him to interpret this music in the way Jarrett might have performed it. With the assistance of two sensitive and renowned musicians in the forms of Buster Williams and Billy Hart, as well as a fine production team (executive producer François Zalacain and engineer Chris Allen) this is an album that proclaims the legacy of Keith Jarrett without reducing to mimicry or hastily-arranged covers.

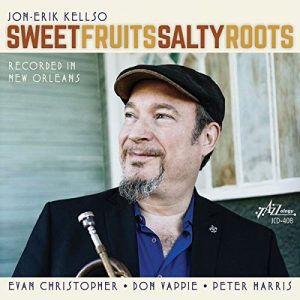

JON-ERIK KELLSO: “SWEET FRUITS, SALTY ROOTS” (Jazzology 408)

One of jazz’s greatest characteristics is the coexistence of styles. Young musicians can become professionals playing any style they wish. After their debut, they can decide to change styles, or develop within their original genre. While some jazz fans still indulge in the “hipper-than-thou” game, many realize that the way this music will continue to live is for all of the styles to survive into future generations. For several years, trumpeter Jon-Erik Kellso and clarinetist Evan Christopher have been diligent practitioners of classic New Orleans jazz. Their new CD, “Sweet Fruits, Salty Roots” was recorded in the Crescent City in May 2019 with (shock of shocks!) all of the musicians in the same room. The duo became a quartet with the addition of guitarist Don Vappie and bassist Peter Harris. Although it is not mentioned anywhere in the notes, this is the same instrumental combination as the famous Sidney Bechet/Muggsy Spanier Big Four recordings of 1940. However, this group achieves an intimacy that the Bechet/Spanier quartet never strove for (and one that would have been obscured in the present recording had a drummer been added). What Kellso and Christopher duplicate from Spanier and Bechet is the equal pairing of brass and woodwind voices in the front line. Also, each hornman reveals a uniquely personal approach to the classic style. On “Russian Lullabye”, they exchange leads on a dime, each listening intently to the other and adjusting their lines to compliment the other. Kellso’s tone carries a distinctive and charming rasp, while Christopher’s outstanding technique allows him to navigate the wide range of his instrument. Christopher also avoids the long phrases of traditional clarinetists, preferring to punch out smaller phrases to intertwine with his front-line partner. Unfortunately, Duke Ellington’s “Have a Heart” (aka “Lost in Meditation”) doesn’t work out very well: Kellso’s plunger work does not focus on a particular timbre, and Christopher sounds like he wants to emulate Barney Bigard. There’s really no need for such effects: Ellington’s music stands up as straight-ahead music without any of the Ellington band’s unique sounds (Their conception of Johnny Hodges’ “One for the Duke” later in the album is much more convincing). One great aspect of the current album is the group’s resurrection of forgotten or neglected songs. After hearing Kellso and Christopher’s versions of Fats Waller’s “Lonesome Me” and Rudy Vallee’s “Deep Night”, you’ll wonder why these songs didn’t catch on. Many fans know “No Regrets” from Billie Holiday’s famous recording, and Kellso has integrated a few pieces of that old arrangement into his current setting. Christopher is showcased on “Old Stack O’Lee Blues” starting with a mysterious intro for chalumeau-register clarinet and bass, and leading into a wonderfully structured solo. Later in the track, Kellso counters with a soulful lead on the penultimate chorus. The playlist also includes three spirited pieces associated with Louis Armstrong: “Coal Cart Blues”, ”Heah Me Talkin’ to Ya” and “Wild Man Blues”. On all three tracks, the band shows their respect for Pops, and never sacrifices the swing. If you still think of traditional jazz as “Dixieland” (and all the horrors that label invokes), give this recording a chance. It has a refreshing take on the style, and it proves that the style is alive and well.

One of jazz’s greatest characteristics is the coexistence of styles. Young musicians can become professionals playing any style they wish. After their debut, they can decide to change styles, or develop within their original genre. While some jazz fans still indulge in the “hipper-than-thou” game, many realize that the way this music will continue to live is for all of the styles to survive into future generations. For several years, trumpeter Jon-Erik Kellso and clarinetist Evan Christopher have been diligent practitioners of classic New Orleans jazz. Their new CD, “Sweet Fruits, Salty Roots” was recorded in the Crescent City in May 2019 with (shock of shocks!) all of the musicians in the same room. The duo became a quartet with the addition of guitarist Don Vappie and bassist Peter Harris. Although it is not mentioned anywhere in the notes, this is the same instrumental combination as the famous Sidney Bechet/Muggsy Spanier Big Four recordings of 1940. However, this group achieves an intimacy that the Bechet/Spanier quartet never strove for (and one that would have been obscured in the present recording had a drummer been added). What Kellso and Christopher duplicate from Spanier and Bechet is the equal pairing of brass and woodwind voices in the front line. Also, each hornman reveals a uniquely personal approach to the classic style. On “Russian Lullabye”, they exchange leads on a dime, each listening intently to the other and adjusting their lines to compliment the other. Kellso’s tone carries a distinctive and charming rasp, while Christopher’s outstanding technique allows him to navigate the wide range of his instrument. Christopher also avoids the long phrases of traditional clarinetists, preferring to punch out smaller phrases to intertwine with his front-line partner. Unfortunately, Duke Ellington’s “Have a Heart” (aka “Lost in Meditation”) doesn’t work out very well: Kellso’s plunger work does not focus on a particular timbre, and Christopher sounds like he wants to emulate Barney Bigard. There’s really no need for such effects: Ellington’s music stands up as straight-ahead music without any of the Ellington band’s unique sounds (Their conception of Johnny Hodges’ “One for the Duke” later in the album is much more convincing). One great aspect of the current album is the group’s resurrection of forgotten or neglected songs. After hearing Kellso and Christopher’s versions of Fats Waller’s “Lonesome Me” and Rudy Vallee’s “Deep Night”, you’ll wonder why these songs didn’t catch on. Many fans know “No Regrets” from Billie Holiday’s famous recording, and Kellso has integrated a few pieces of that old arrangement into his current setting. Christopher is showcased on “Old Stack O’Lee Blues” starting with a mysterious intro for chalumeau-register clarinet and bass, and leading into a wonderfully structured solo. Later in the track, Kellso counters with a soulful lead on the penultimate chorus. The playlist also includes three spirited pieces associated with Louis Armstrong: “Coal Cart Blues”, ”Heah Me Talkin’ to Ya” and “Wild Man Blues”. On all three tracks, the band shows their respect for Pops, and never sacrifices the swing. If you still think of traditional jazz as “Dixieland” (and all the horrors that label invokes), give this recording a chance. It has a refreshing take on the style, and it proves that the style is alive and well.

CHRIS PATTISHALL: “ZODIAC” (self-released)

Mary Lou Williams composed her “Zodiac Suite” in 1945, recording it in trio format and for small orchestra. Williams’ status as one of jazz’s greatest practitioners (and certainly the premier female jazz musician of the classic era) has led to several new performances of this suite, but none have stirred the imagination more than the new recording, “Zodiac” by Chris Pattishall. With the assistance of sound designer Rafiq Bhatia, Pattishall has transformed the original into the 21st century by expanding the sonic range, and by allowing his soloists free reign to improvise in contemporary harmonic structures. In the opening track, “Taurus”, Riley Mulherkar’s trumpet sound is looped and altered through Bhatia’s soundboard. On “Cancer”, Ruben Fox plays an outstanding tenor solo which ends in an explosive duet with drummer Jamison Ross. Williams stated that she would have loved to had horns added to her trio recording; listen to Fox rip through the changes on “Virgo” on this album and just imagine how Ben Webster would have handled the same material! Pattishall maintains the responsibility of playing Williams’ original parts, but he doesn’t leave himself much room to stretch out on his own. He does play an extended harmony solo on the final track, “Aries”, which also displays the superb work of bassist Marty Jaffe and drummer Jamison Ross. Pattishall is to be commended for keeping “Zodiac Suite” within its original compact structure, but perhaps a little expansion in length might have allowed for more explorations by this very talented ensemble. What would have Mary Lou Williams thought of this version? As a musician who adopted the new styles of jazz as they appeared (and was even brave enough to play a duo concert with the uncompromising free jazz icon Cecil Taylor) I believe she would have been delighted at the harmonic expansions and at the performances of the soloists. The electronic manipulations might have raised her eyebrows, but she might have been curious to see how those unusual sounds were produced. And even if this modern transformation is not to everyone’s taste, I feel confident that Mary Lou Williams and her music are not likely to be forgotten in our collective lifetimes. With her major recordings (including “Zodiac Suite”) in the custody of the Smithsonian Institute, her music should be available for many years to come.

trio format and for small orchestra. Williams’ status as one of jazz’s greatest practitioners (and certainly the premier female jazz musician of the classic era) has led to several new performances of this suite, but none have stirred the imagination more than the new recording, “Zodiac” by Chris Pattishall. With the assistance of sound designer Rafiq Bhatia, Pattishall has transformed the original into the 21st century by expanding the sonic range, and by allowing his soloists free reign to improvise in contemporary harmonic structures. In the opening track, “Taurus”, Riley Mulherkar’s trumpet sound is looped and altered through Bhatia’s soundboard. On “Cancer”, Ruben Fox plays an outstanding tenor solo which ends in an explosive duet with drummer Jamison Ross. Williams stated that she would have loved to had horns added to her trio recording; listen to Fox rip through the changes on “Virgo” on this album and just imagine how Ben Webster would have handled the same material! Pattishall maintains the responsibility of playing Williams’ original parts, but he doesn’t leave himself much room to stretch out on his own. He does play an extended harmony solo on the final track, “Aries”, which also displays the superb work of bassist Marty Jaffe and drummer Jamison Ross. Pattishall is to be commended for keeping “Zodiac Suite” within its original compact structure, but perhaps a little expansion in length might have allowed for more explorations by this very talented ensemble. What would have Mary Lou Williams thought of this version? As a musician who adopted the new styles of jazz as they appeared (and was even brave enough to play a duo concert with the uncompromising free jazz icon Cecil Taylor) I believe she would have been delighted at the harmonic expansions and at the performances of the soloists. The electronic manipulations might have raised her eyebrows, but she might have been curious to see how those unusual sounds were produced. And even if this modern transformation is not to everyone’s taste, I feel confident that Mary Lou Williams and her music are not likely to be forgotten in our collective lifetimes. With her major recordings (including “Zodiac Suite”) in the custody of the Smithsonian Institute, her music should be available for many years to come.