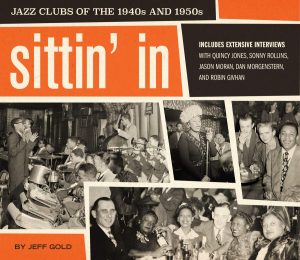

On March 12, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused the shutdown of performing venues all over the world. Musicians suffer the most from this long-enforced hiatus, but audiences also long for the time when they can experience the arts in person. Jeff Gold’s new pictorial book, “Sittin’ In” (Harper Design) examines jazz nightclubs of the 1940s and 1950s through the perspective of the audiences—or more precisely, the collective lenses of free-lance photographers who worked in the clubs during that period. These photographers were not established giants like Richard Avedon, Alfred Eisenstaedt, or Weegee, but part-time nightclub workers who roved around the audience snapping souvenir photos for the clients. Except when the club’s featured artists would pose with their enthusiastic fans, none of the subjects or their photographers are identified.

1950s through the perspective of the audiences—or more precisely, the collective lenses of free-lance photographers who worked in the clubs during that period. These photographers were not established giants like Richard Avedon, Alfred Eisenstaedt, or Weegee, but part-time nightclub workers who roved around the audience snapping souvenir photos for the clients. Except when the club’s featured artists would pose with their enthusiastic fans, none of the subjects or their photographers are identified.

It is what we see within these collected photos that captures our imagination. Here are Blacks and Whites co-mingling at a large table. They are dressed up, paying attention to the music, and generally having a good time. We see soldiers and sailors in the company of lovely women and wonder if the men came back home from their military service, and whether the couples remained intact after this night. Sometimes the mixtures fall out of the traditional couple patterns: a woman at the Famous Door with a suitor on each side, or a group of five African-American men with two Caucasian women at the Savoy Ballroom. Because we know nothing about these people, we can’t jump to conclusions about their actions or motives. In addition to the photos, there are numerous handbills and picture postcards of the clubs. When the club was the site of a famous recording, we can imagine what the artists saw as they looked out from the stage, or we can place ourselves in one of the booths as the extraordinary music filled the room. The menus are a special treat: imagine getting a broiled sirloin steak for only $1.75 or Welsh Rarebit for $1.00!

To put this material into context, Gold interviewed Quincy Jones, Sonny Rollins, Jason Moran, Dan Morgenstern, and Robin Givhan about the clubs, the music, integration, and the attire. The interviews occurred in the order above, and Gold ties them together by quoting his previous interviewees to the current subject. This also helps to solidify some of the claims in the book, notably Jones’ assertion that in the pre-Civil Rights days of the 40s and 50s, all of the major clubs in New York were integrated, a position backed up by Rollins and Morgenstern, as well as many of the souvenir photographs. Jones and Rollins tell wondrous tales of nights in the audience or on the stage, while Morgenstern, who was an ardent fan before becoming a premier jazz historian, gives a panoramic view of the many clubs in Manhattan. Moran’s thorough knowledge of jazz history allows him to comment on the music and atmosphere of the clubs. Givhan, who—like Moran—was not yet born when the vintage photos were taken, offers her perspective on the fashion of the era, and on several of the group photos.

Gold assembled this material from a memorabilia collection he purchased a few years ago. It is therefore limited by mementos from the clubs visited by the original owners. There are examples from clubs in New York, Boston, Atlantic City, Cleveland, Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Detroit, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. But even though the chapter prologues contain stories about legendary clubs like Storyville (Boston), Lindsay’s Sky Bar (Cleveland), and the Reno Club (Kansas City), the book does not include any photos of these nightspots. Further, there appears to be very little information about the eventual demise of these clubs. Apparently, some of these venues just closed their doors after a bad stretch of business.

In the past months, we have lost several major jazz clubs including The Jazz Standard in New York, The Blue Whale in Los Angeles, and El Chapultepec in Denver. Many more may fall on the slow track to normalcy. A book like “Sittin’ In” is particularly appropriate as the COVID pandemic winds down. Let us remember how much we miss our performance venues and then back up that feeling by patronizing those clubs many times over. We owe it to the musicians and club workers. We also owe it to ourselves.