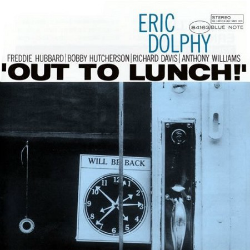

In the original liner notes to Eric Dolphy’s “Out To Lunch”, A.B. Spellman writes that “this is not music to roller skate by”. Emphatically so. In fact, this album can be difficult for listeners giving it their full attention. I’ve struggled with this album for years: a college roommate gave me a copy when I was deep into Dolphy’s work, but I was turned off by the disparity between Dolphy’s evocative compositions and the seeming chaos of the free solos. I still bear some of that feeling, but upon listening to this album in the last few days, I’ve realized that the very disparity I recognized was exactly what Dolphy wanted, and that “Out To Lunch” was an effort to break our expectations about the very nature of jazz.

In the original liner notes to Eric Dolphy’s “Out To Lunch”, A.B. Spellman writes that “this is not music to roller skate by”. Emphatically so. In fact, this album can be difficult for listeners giving it their full attention. I’ve struggled with this album for years: a college roommate gave me a copy when I was deep into Dolphy’s work, but I was turned off by the disparity between Dolphy’s evocative compositions and the seeming chaos of the free solos. I still bear some of that feeling, but upon listening to this album in the last few days, I’ve realized that the very disparity I recognized was exactly what Dolphy wanted, and that “Out To Lunch” was an effort to break our expectations about the very nature of jazz.

While “Out To Lunch” has not dated in the slightest, I wonder if it would have sounded different had it been recorded at a time other than February 1964. That was a particularly volatile month in United States history as well as in jazz history. There were boycotts against the public schools in New York City, the release of the accused murderer of Medgar Evers after a mistrial in the corrupt Southern judicial system, and the Beatles made their US debut on the Ed Sullivan show. Dolphy had returned to the Charles Mingus Jazz Workshop after several months of free-lancing, and the two men were expanding the horizons of their free musical conversations. And within the same week, Art Blakey (with Freddie Hubbard) recorded the explosive album “Free For All” and Miles Davis (with Tony Williams) performed a classic concert at Philharmonic Hall which yielded the albums “Four and More” and “My Funny Valentine”. Bobby Hutcherson and Richard Davis had just recorded the turbulent Blue Note album “Judgment” with leader/pianist Andrew Hill and drummer Elvin Jones. So when Dolphy, Hubbard, Hutcherson, Davis and Williams assembled at the Van Gelder Studios on February 25, the air was ripe for new approaches to jazz and improvisation.

“Out To Lunch” was revolutionary on nearly every front. In addition to dispelling the notion that improvised solos should maintain the mood of the melody, Dolphy called for his sidemen to rethink their preconceived notions about improvisation. Dolphy developed highly individualistic sounds on bass clarinet, alto sax and flute, and his wildly imaginative improvisations expanded the harmonic scope of the music. Hubbard’s solos on “Free For All” had pushed the boundaries of standard bop harmony, but they were still tonally based; on “Out To Lunch”, he organized his solos in a completely different manner, manipulating motivic cells to build his statements. The rhythm section sounds entirely different than any other rhythm section of its time. Not only are they free from keeping time, the pulse is allowed to fluctuate as the pieces evolve (this concept was also present on Hill’s “Judgment”). Indeed, all three of these musicians are commentators, not timekeepers. At times, Hutcherson plunks out a single note behind a soloist, and Williams’ rapport with the group is much more free-flowing than it was with Miles Davis at the time (when interviewed for the liner notes, Dolphy said that Williams “doesn’t play time; he just plays.”) Richard Davis also had considerable freedom in his role: on the title track, the bass part had no time signature at all, and that allowed Davis to lead and follow the group in any meter.

Once the listener takes this music on its own terms, a wide variety of pleasures emerge. The rhythm section is amazing throughout the album, but follow them through “Gazzelloni” as they shift the levels of energy and musical direction without disrupting the flow of the music. From Williams’ animated commentary alongside Dolphy’s flute to the near dissipation of the rhythm in the middle of Hubbard’s solo, and then back up again behind Hutcherson, the rhythm section seems to spontaneously find its own path. The Dolphy/Davis duets that frame “Something Sweet, Something Tender” are reminiscent of their marvelous duets from the Alan Douglas sessions of the previous year, and Hubbard’s featured spot on that track is quite effective, even though I suspect that his part was mostly written out. And after the shock of Dolphy’s squawking bass clarinet entrance on “Hat and Beard”, listen to how his rhythms seem utterly divorced from the ground beat or any standard musical notation. Against the rhythm’s ebb and flow behind Dolphy’s alto on the title track, we can hear that Dolphy seemed far advanced of Ornette Coleman in sound, ideas and rhythmic conception. Davis’ unaccompanied bass solo on the same track offers substantial proof of his unparalleled virtuosity and provides a momentary break from the dense layers of the rhythm section. When everyone returns after Davis, there is an episode that sounds like a series of fours with Williams, but it never really turns out that way. Instead, it’s another example of how Dolphy and company re-examined the very framework of this music.

By 1964, Eric Dolphy was still a controversial player, but few musicians doubted his extraordinary gifts as an instrumentalist. “Out To Lunch” showed that Dolphy was also a fine composer and bandleader, with daring ideas of how music could be played and presented. Sadly, he had little opportunity to further develop these ideas. He traveled to Europe with Mingus in the spring of 1964, producing several recordings, but few under his own name. He remained in Europe after the tour in search of greater performing opportunities, but while in Germany, he went into a diabetic coma and died on June 28, 1964. Isolated elements of the concepts from “Out To Lunch” appeared on other Blue Note albums and in the mid-60s Miles Davis Quintet, but as a whole, this bold musical experiment seems to have gone undeveloped in the past 48 years. Perhaps Dolphy’s innovations wouldn’t seem so strange today if others would take up his challenge.

This review is based on a new high definition remaster available from HD Tracks. This company has reissued several Blue Note classics and the sound is truly remarkable. While no amount of remastering can completely cure all of the problems of analog tape (there are occasional spots of distortion and a bad instance of print-through on “Out To Lunch”), the presence and vitality of the sound is far superior to any previous editions of these albums. The FLAC versions of these albums were provided for this review, and it should be noted that these files are quite large—about 2 GB for a 40 minute album—and they must be compressed significantly to burn them onto CDs. However, that compression did not seem to diminish the superior fidelity of these fine remasters.