It is said of fans and musicians alike that we don’t find music, but that music finds us. When that meeting happens, music grabs on and refuses to let go. How many times has the story been told of the musician who has suffered an injury so severe that it would all but impossible to continue playing? Yet, the outcome is the same: despite the doctor’s advice, the musician somehow finds a way to continue his career. Such stories sound like myths, but they actually happen. Consider the story of Chicago pianist Norman Malone, who suffered paralysis on his right side when his mentally-deranged father tried to kill him and his siblings. Malone had only played piano for five years, but he decided to continue studying with a focus on repertoire written for the left hand alone. His triumphal story is presented in a new documentary, “For the Left Hand”. It’s not a jazz film, but any musician will appreciate Malone’s struggles.

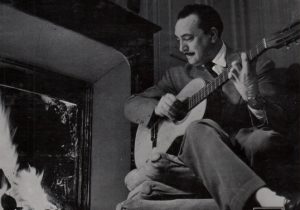

An earlier and more famous version of the story concerns Django Reinhardt, whose body was severely burned when his caravan trailer caught fire on the night of November 2, 1928. Reinhardt was only 18 years old, but he had been a professional musician since the age of 12, performing popular songs on the banjo-guitar. He ignored the doctor’s warnings about finding a new career, and when his brother Joseph placed a guitar in the hospital bed, it wasn’t long before Reinhardt was developing a new technique. He resumed his recording career in 1931, and sometime during this period, he was exposed to American jazz through Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Dallas Blues”. One story says that Reinhardt openly wept at the beauty of the music. Regardless of the story (and the tears), there is no doubt that Reinhardt was inspired to use his new technique to play jazz.

An earlier and more famous version of the story concerns Django Reinhardt, whose body was severely burned when his caravan trailer caught fire on the night of November 2, 1928. Reinhardt was only 18 years old, but he had been a professional musician since the age of 12, performing popular songs on the banjo-guitar. He ignored the doctor’s warnings about finding a new career, and when his brother Joseph placed a guitar in the hospital bed, it wasn’t long before Reinhardt was developing a new technique. He resumed his recording career in 1931, and sometime during this period, he was exposed to American jazz through Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Dallas Blues”. One story says that Reinhardt openly wept at the beauty of the music. Regardless of the story (and the tears), there is no doubt that Reinhardt was inspired to use his new technique to play jazz.

Eventually, Reinhardt would be acclaimed as “the first original jazz soloist from outside America”, but it took several years for him to move away from the flashy tremolos and other guitar effects of his past toward a pure jazz solo style built upon the development of melodic motives, energetic swinging rhythm, and harmonic experimentation. His style evolved as his star status grew with his cooperative band, the Quintette of the Hot Club of France. The QHCF’s personnel was unique in its own right, utilizing the elegant violin of Stephane Grappelli, Django Reinhardt’s solo acoustic guitar, plus a rhythm section of two more acoustic guitars and acoustic bass. Without horns, drums, or vocalists, the QHCF demanded close listening from its audience. They found their own unique brand of swing, and within this setting, Reinhardt began to develop his new jazz solo style.

Oh, Lady Be Good

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Roger Chaput, Joseph Reinhardt (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b).

Paris, December 28, 1934

From the very first session of the QHCF, “Oh, Lady Be Good” shows the group still getting its bearings. The swing rhythms are still a little jerky, and part of the problem is Louis Vola’s two-beat bass pattern. On the occasions where he plays four beats to the bar, the rhythmic issues straighten themselves out almost instantly. After Grappelli and Reinhardt’s opening figure, the guitarist takes his first solo, paraphrasing the Gershwin melody as he goes. This was a typical setup for the early QHCF sides, and Reinhardt was very adept at alternating between melody and improvisation. What is also present is Reinhardt’s fine sense of sequencing and developing motives, as displayed in a superbly executed sequence near the end of his second chorus. However, he didn’t have a wide range of licks, and he had not yet developed a sense of solo structure. There is a hint of future developments during his second solo as he strongly chords to designate the surprise modulations. Grappelli seems a little less polished than we might expect, but he delivers two red-hot solos that raise the intensity of the performance.

St. Louis Blues

Stephane Grappelli & His Hot Four: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Baro” Ferret, Joseph Reinhardt (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b).

Paris; September 30, 1935

Grappelli might have been the leader on this date, but Reinhardt is the soloist for all but the last minute of this record. For anyone unaware of the guitarist, the unaccompanied introduction might make them think that they were hearing a classical player. Yet, as Reinhardt slides into a slow-walk tempo and the opening melody of “St. Louis Blues”, there is no doubt that his heart lies in jazz. He makes effective use of bent notes in the opening chorus, and his flashy but tasteful runs add dramatic contrast. When he goes to the tango section, he adds to the drama with strong lines in parallel octaves. The tempo picks up as the band returns to the blues choruses, and Reinhardt’s final chorus is marked by block chords and a dramatic tremolo. When Grappelli enters, Reinhardt steals the spotlight back with his unique accompanying style featuring choppy block chords and tremolos at the turnarounds.

After You’ve Gone

After You’ve Gone

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Baro” Ferret, Joseph Reinhardt (rhythm g); Lucien Simoens (b); Freddie Taylor (v).

Paris, May 4, 1936

After its initial recordings on Ultraphone and Decca, the QHCF moved to the HMV label. “After You’ve Gone” was recorded on their first session for the label and there seems to have been some growing pains. The balance is not as good as on the other labels, with especially weak recording of the bass. The opening chorus is by Grappelli this time around and he is immediately followed by the Armstrong-inspired singing of Freddie Taylor. It seems that everyone is holding back in these opening choruses, and sure enough, as soon as Taylor is finished, the intensity goes up as Reinhardt goes into a finger-busting chorus filled with fast arpeggios and runs, and concluding with a chorded intro to Grappelli. The violinist takes charge, building the intensity with every chorus. The breaks, built into the tune at the end of each 16-bar section, seemed to have little effect on Taylor, but each time Reinhardt and Grappelli hit them, they added to the growing excitement.

Shine

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Baro” Ferret, Joseph Reinhardt (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b); Freddie Taylor (v).

Paris, October 15, 1936

Django Reinhardt’s solo on “Shine” was one of his finest to that point in his career. In it, he forms a direct link to Wes Montgomery by using a similar concept in building a solo. Although the building blocks are similar, the overall effect is different. Here, Reinhardt plays in single lines throughout the first chorus and moves to octaves at the beginning of the second. The block chords don’t come in until the end as Reinhardt is accompanying Grappelli. As Reinhardt gained more experience, he became an expert in pacing his solos so they would make sense as a musical entity. Instinctively, he seemed to know the precise moment where block chords would properly set off his single lines. In the final choruses, Reinhardt and Grappelli are basically a duet with the rest of the band humming along in the background. Reinhardt had refined his accompanying style as well, retaining its active stance in the music, but no longer stealing the spotlight away from Grappelli.

Hot Lips

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Baro” Ferret, Marcel Bianchi (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b).

Paris, April 22, 1937

“Hot Lips” must have seemed a strange choice for the QHCF. Although the song was only 15 years old at the time, it was certainly dated as a remnant of 1920s hot-cha. After a plethora of recordings in the twenties, the song went unrecorded by jazz artists for nearly five years. Significantly, the two recordings from 1935 and 1936 were made in London, and perhaps Grappelli or Reinhardt heard one of those versions and decided to try it with the QHCF. At any rate, this is a very pleasant medium-tempo version of the song. Grappelli starts off the proceedings with a fairly straight reading of the melody over the chunk, chunk-a-chunk rhythm of the guitars. Reinhardt’s solo is marked by a long section in parallel sixths. Usually, he avoided using the same sound for several bars, but here, there is a mild amount of experimenting going on, first to see how long he could maintain interest with the same voicing, and second, to see if a slight change would break up the monotony. As he finishes an eight-bar phrase, he fills in the note between the open sixth creating a chord voicing straight out of Alvino Rey! In fact, the figure he plays involves moving the voicing between chords a half-step apart, which is an easy effect to play on a slide guitar. The effect is a little corny and Reinhart didn’t use it much, but for an old obscure song, it worked well enough.

When Day Is Done

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Baro” Ferret, Marcel Bianchi (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b).

Paris, April 22, 1937

Reinhardt opens this version of “When Day Is Done” with a dramatic unaccompanied guitar cadenza. I suspect he was trying to emulate Louis Armstrong’s introduction to “West End Blues” and indeed, one can imagine young guitarists being bowled over by the recording. It impresses me as well, but the solo that follows is quite special for what isn’t there. As the introduction has plenty of contrast between chorded sections and single lines, the solo is entirely comprised of single-line melody and embellishment. The filigrees are tasty, the bent notes are heart-rending, and there are no tremolos or other effects to upset the mood. Later, Reinhardt picks up the tempo for Grappelli’s entrance and from there until the record’s end, we have an out-chorus that is well-played, if rather routine for this group. This time, the disconnect is too great from what came before. Time to go back and listen to the first half of the record again!

Japanese Sandman

Japanese Sandman

Dicky Wells & His Orchestra: Bill Coleman (tp); Dicky Wells (tb); Django Reinhardt (g); Dick Fullbright (b); Bill Beason (d).

Paris, July 7, 1937

Even before the Quintette of the Hot Club of France started recording, Django Reinhardt was a first-call player whenever American artists recorded in Paris. Considering he could barely read and write his own name, let alone music scores, it was amazing that Reinhardt achieved such a status. But his ear was precise and he could translate what he heard to the guitar with stunning accuracy, and that is a major part of his legendary reputation.

Bill Coleman and Dicky Wells were touring Paris as part of the Teddy Hill Orchestra when they recorded this session for Swing (Dizzy Gillespie was also with the band, and ironically, he was the only trumpeter from the band not invited to play at the session!) This delightful version of “Japanese Sandman” was the last song of the session. With the other trumpeters excused for the day, this piece became a relaxed jam session featuring solos by all three principals. Wells is up first, barely touching the melody before moving into his own invention. Yet he never loses sight of the opening motive and many of his ideas are rhythmically or melodically related to it. Coleman follows with his sunny, open tone. His first half-chorus features a set of perfectly-balanced phrases. Then the last phrase spills into the bridge and his phrasing shifts three beats off the form. Coleman keeps things that way until he ties it all up with a beautifully-played 6-bar phrase. Then Reinhardt steps up with a mostly single-string solo that features some intriguing harmonic choices in the 5th-8th bars. The rest of the solo is rather straight-forward harmonically, so it’s hard to know whether he was fully aware of what he was doing and if he considered it a momentary misstep (If Dizzy had been at the session, he would have known!). However, it was not an isolated incident and Reinhardt, who later expressed admiration for the harmonic innovations of Gillespie and Charlie Parker, would experiment again with advanced harmonies in the next few years—several years before bebop was born.

Minor Swing

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Eugène Vées, Joseph Reinhardt (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b).

Paris, November 25, 1937

“Minor Swing” may be the most popular record Django Reinhardt ever made. The calm introduction offers little clues to what follows, but it does have one unusual feature for this group: a bass solo! When the second bass break suddenly becomes very aggressive, Reinhardt kicks off the main tune, the group lays into the minor chord sequence, and we’re in for a wild ride! Reinhardt’s fiery solo stays in single-string for the first two choruses, achieving its passion through dramatic bent notes. Then in the third chorus, he combines a block chord, a tremolo, and a glissando up and down the guitar, making his instrument roar like a lion. Grappelli picks up on the growing intensity and his violin solo builds and builds with each successive chorus. Rhythm guitarists Eugène Vées and Joseph Reinhardt are excellent on this recording—I still marvel at how they could create such a strong backbeat without a drummer behind them!

And then there’s the talking. Reinhardt had quite a reputation for shouting verbal encouragements during recording sessions. According to Benny Carter, it was Reinhardt that shouted “Go on, go on” to Coleman Hawkins on their 1937 studio recording of “Crazy Rhythm”. (The fact that Hawkins did go on—unheard of in those days of 3-minute 78s—created one of the greatest jazz recordings of the era). On “Minor Swing”, we can hear Reinhardt egging on Grappelli as the performance builds. It’s only at the very end of the record, when the entire group says “Oh, Yeah” in rough unison that we realize the QHCF has played a little joke on us, brilliantly set up during the course of the record.

Blues

Philippe Brun (tp); Stephane Grappelli (celeste); Django Reinhardt (g).

Paris, December 27, 1937

One of the finest French jazz trumpeters of his day, Philippe Brun is nearly forgotten now and except for his collaborations with Django Reinhardt and Alix Combelle, few of his recordings have been reissued. Inspired by Bix Beiderbecke, Brun’s lovely tone shone through even when, as on “Blues”, he played in a cup mute. I don’t know how the musicians decided on the unusual instrumentation for this recording, but it created a delightful and delicate sort of chamber jazz, and it was a precursor to Edmond Hall‘s Celeste Quartet session of 1941. (Was it an inspiration? Who knows if any member of Hall’s pickup group ever heard this recording? The entire Hall session, featuring Hall (cl); Meade Lux Lewis (celeste); Charlie Christian (g), and Israel Crosby (b) is included at the end of the above playlist.)

One of the finest French jazz trumpeters of his day, Philippe Brun is nearly forgotten now and except for his collaborations with Django Reinhardt and Alix Combelle, few of his recordings have been reissued. Inspired by Bix Beiderbecke, Brun’s lovely tone shone through even when, as on “Blues”, he played in a cup mute. I don’t know how the musicians decided on the unusual instrumentation for this recording, but it created a delightful and delicate sort of chamber jazz, and it was a precursor to Edmond Hall‘s Celeste Quartet session of 1941. (Was it an inspiration? Who knows if any member of Hall’s pickup group ever heard this recording? The entire Hall session, featuring Hall (cl); Meade Lux Lewis (celeste); Charlie Christian (g), and Israel Crosby (b) is included at the end of the above playlist.)

Brun takes the first solo, and although he’s the featured player for the side, he never tries to impress with flashy displays of technique. Instead, he plays a simple, soulful statement that cuts right to the core. Grappelli (who was also an excellent pianist) enjoys playing around on the celeste, but Reinhardt’s solo is quite serious and studied. There are no guitar effects, just a passionate single-string solo made up of perfectly-sculpted phrases, with a surprising turn to the low register as Brun returns. If Brun had a weakness, it was his sense of swing. Reinhardt offers some help in the final chorus, as he picks up on Brun’s jerky shuffle rhythm and adapts it into his accompaniment, thereby bringing Brun a little closer to modern swing style.

Honeysuckle Rose

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Eugène Vées, Roger Chaput (rhythm g); Louis Vola (b).

London, January 31, 1938

In a way, this 1938 version of “Honeysuckle Rose” is a throwback to the earliest recordings of the QHCF. It is set in a bouncy two-beat, and Reinhardt takes the first solo, going back and forth between melody and improvisation. But closer listening shows that the group had come a long way in just over three years. First of all, Reinhardt’s style had evolved to primarily single-string solos. While his earlier recordings showed him to be a master of varying styles from single-string to chords to tremolos in an effort to maintain listener interest, his recordings from this period show new confidence in the strength of his single lines. His “Honeysuckle” solo has only one little octave outburst, yet we are captivated by his solo. He is also more harmonically savvy, and the “outside” note choices he makes sound much more assured than on his “Japanese Sandman” solo of six months earlier. Grappelli’s rhythmic sense is more attuned than on the early sides and his playing displays elegance and fire simultaneously. The little ensemble figure Reinhardt and Grappelli play in the final chorus is simply delightful, and when Grappelli solos during the bridge, there is Django offering vocal encouragement.

earliest recordings of the QHCF. It is set in a bouncy two-beat, and Reinhardt takes the first solo, going back and forth between melody and improvisation. But closer listening shows that the group had come a long way in just over three years. First of all, Reinhardt’s style had evolved to primarily single-string solos. While his earlier recordings showed him to be a master of varying styles from single-string to chords to tremolos in an effort to maintain listener interest, his recordings from this period show new confidence in the strength of his single lines. His “Honeysuckle” solo has only one little octave outburst, yet we are captivated by his solo. He is also more harmonically savvy, and the “outside” note choices he makes sound much more assured than on his “Japanese Sandman” solo of six months earlier. Grappelli’s rhythmic sense is more attuned than on the early sides and his playing displays elegance and fire simultaneously. The little ensemble figure Reinhardt and Grappelli play in the final chorus is simply delightful, and when Grappelli solos during the bridge, there is Django offering vocal encouragement.

Tea For Two

Quintette of the Hot Club of France: Stephane Grappelli (vln); Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Baro” Ferret, Joseph Reinhardt (rhythm g); Emmanuel Soudieux (b).

Paris, March 23, 1939

“Tea For Two” must have been one of Reinhardt’s favorite songs at this period, as he recorded it five times between 1937-1939. Three of those versions were made by the QHCF in 1939 for the Decca label. This version stands out from the others for its beautiful relaxed tempo and for Reinhardt’s amazing solo. The cut opens with a violin and guitar duet on the verse. Grappelli is as elegant as ever, but Reinhardt is feeling rhapsodic, and as he begins his solo on the tune he goes into a breathtaking run, astounding not only for its length but also for its asymmetrical architecture. Maintaining his penchant for single-line solos, his second eight features a brilliant development of the song’s primary motive. In the next eight, he develops one of his own lines but then returns to examining the original tune to finish his chorus. All of this is done so artfully that the casual listener can barely tell what’s going on. Reinhardt’s accompaniment style also includes a new development: there is a wonderful moment during Grappelli’s solo where Reinhardt hits a tremolo at full strength, but then immediately brings the volume down. In classical music, that’s known as a forte-piano, but it is rarely used in jazz. Here, it is a perfect way to balance the QHCF’s usual rough-and-ready style with the tender reading of a timeless standard.

I’ll See You in My Dreams

Django Reinhardt (solo g); Pierre “Barot” Ferret (rhythm g); Emmanuel Soudieux (b).

Paris, June 30, 1939

Recorded just two months before the outbreak of a war that would change his life and career forever, Django Reinhardt’s trio version of “I’ll See You in My Dreams” is a brilliant summation of his late-30s solo style with intriguing notions for future developments. The solo is almost entirely in single lines, and as we listen to Reinhardt create this two-and-a-half-minute masterpiece, it is like we are inside his head as he discovers and develops ideas. The precise musical logic that had always been present in Reinhardt’s playing appears in extremely sharp focus as he takes motive after motive and turns them every which way until they become new phrases that he can manipulate. In one case, that motive is one note, and as he plays that note several times, he subtly changes the sound by changing the way he attacks the string. If his harmonic experiments are limited to a short passage early on, he revisits an old challenge in offsetting rhythms (listen again to “Oh, Lady Be Good”!) and near the end of the side, there is a marvelous sequence with quarter-note triplet figures against the steady four-beat of Ferret and Soudieux. Reinhardt would have another 14 years on the planet, but even if his career would have ended at this point, recordings like this one would have ensured his immortality.

Recorded just two months before the outbreak of a war that would change his life and career forever, Django Reinhardt’s trio version of “I’ll See You in My Dreams” is a brilliant summation of his late-30s solo style with intriguing notions for future developments. The solo is almost entirely in single lines, and as we listen to Reinhardt create this two-and-a-half-minute masterpiece, it is like we are inside his head as he discovers and develops ideas. The precise musical logic that had always been present in Reinhardt’s playing appears in extremely sharp focus as he takes motive after motive and turns them every which way until they become new phrases that he can manipulate. In one case, that motive is one note, and as he plays that note several times, he subtly changes the sound by changing the way he attacks the string. If his harmonic experiments are limited to a short passage early on, he revisits an old challenge in offsetting rhythms (listen again to “Oh, Lady Be Good”!) and near the end of the side, there is a marvelous sequence with quarter-note triplet figures against the steady four-beat of Ferret and Soudieux. Reinhardt would have another 14 years on the planet, but even if his career would have ended at this point, recordings like this one would have ensured his immortality.

The audio recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.