I know no other musician whose playing better

typifies the spirit of jazz than Roy Eldridge. —NORMAN GRANZ

What impresses me about Norman [Granz] is that everything he’s achieved, he’s gotten by himself. Like most of us musicians, he had to start from scratch to get things going. But he broke through… He made sure the cats got a decent living. He was the first to break down all that prejudice. He put the music up where it belongs. They should make a statue to that cat, and there’s no one else in the…music business I would say that about.

through… He made sure the cats got a decent living. He was the first to break down all that prejudice. He put the music up where it belongs. They should make a statue to that cat, and there’s no one else in the…music business I would say that about.

—ROY ELDRIDGE

Roy Eldridge and Norman Granz met in New York City in early 1942. Eldridge was an established star, while Granz was living on limited funds while between assignments in the military. Granz was already a big fan of the trumpeter, and when his concert and recording projects began to take hold, Eldridge became one of Granz’s first-call players. As the Big Band Era started to decline, the Black Eldridge joined the White bands of Gene Krupa and Artie Shaw as featured soloist. Both Krupa and Shaw did what they could to shield Eldridge from racism on the bandstand, but there was little they could do as the band traveled through the South. While praising the efforts of the leaders, Eldridge later declared that he would never play in a White band again. Granz was also an early champion of civil rights, insisting that all Jazz at the Philharmonic audiences would be racially integrated, or the concert would be canceled. By 1949, Eldridge was a star player in JATP, and even though he left the following year for an extended residency in Paris, he was welcomed back into Granz’s troupe as soon as he returned. What endeared Eldridge to Granz was the trumpeter’s fiercely competitive spirit. He learned to play by studying saxophonists, so he played faster and cleaner than most of his contemporaries. He was a terror in cutting sessions because he could always summon up the energy for one more high-register chorus that would top all of the other players. In 1951, Granz signed Eldridge as one of his recording artists, and the recordings that started then, and continued off-and-on through Eldridge’s retirement from the trumpet in 1980, established Eldridge as one of the great jazz masters.

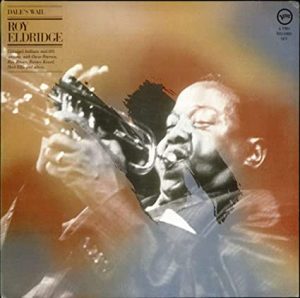

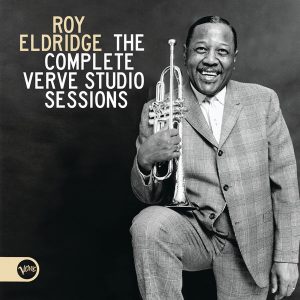

Among the early masterworks was a series of four sessions in 1953 and 1954 featuring Eldridge as the sole horn with the Oscar Peterson Quartet. These recordings were issued on 78 rpm singles, 45 rpm EPs, and both 10” and 12” LPs, but they were eventually collected in a superb Verve double-LP set, “Dale’s Wail”. This music was also included in the 2003 Mosaic collection “The Complete Verve Roy Eldridge Studio Sessions”. The Mosaic is now out-of-print, but the music is still available for streaming on Verve’s similarly-titled digital set. As the Verve double LP covers the Eldridge/Peterson sessions specifically–and is very easy to find in used LP shops—I am using

1954 featuring Eldridge as the sole horn with the Oscar Peterson Quartet. These recordings were issued on 78 rpm singles, 45 rpm EPs, and both 10” and 12” LPs, but they were eventually collected in a superb Verve double-LP set, “Dale’s Wail”. This music was also included in the 2003 Mosaic collection “The Complete Verve Roy Eldridge Studio Sessions”. The Mosaic is now out-of-print, but the music is still available for streaming on Verve’s similarly-titled digital set. As the Verve double LP covers the Eldridge/Peterson sessions specifically–and is very easy to find in used LP shops—I am using  it as the basis of this review. However, I am adding five alternate takes from the Mosaic/Verve sets which complete the sessions.

it as the basis of this review. However, I am adding five alternate takes from the Mosaic/Verve sets which complete the sessions.

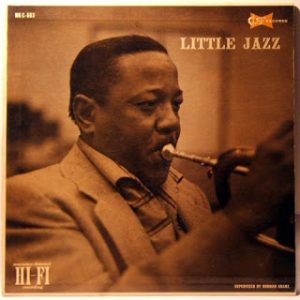

Eldridge’s first studio recording with the Peterson Quartet occurred in New York on February 13, 1953. Peterson—for some reason playing organ on this and the next session—brought along guitarist Barney Kessel and bassist Ray Brown from his working trio, adding drummer J.C. Heard to the group. Even the absence of other horns and the presence of a supportive recording company would not curb Eldridge’s combative nature. Instead, “Roy’s Riff”, a minor key opus which was the opening track from the session features searing muted trumpet coaxed on by organ and drums. Here, Eldridge uses his favorite solo building blocks, gradually adding intensity while moving up to the higher register in each successive chorus. “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” features Eldridge’s open horn, with a distinctive rasp coloring his warm tone. The track displays a contrasting Eldridge technique (usually found in ballads): letting the passion of each line build the intensity rather than rising registers. After such a successful beginning, it is strange to hear Eldridge seemingly battling his own legacy with new versions of two of his old big band features, “Rockin’ Chair” (which he played with Krupa) and “Little Jazz” (his nick-namesake feature with Shaw). To be certain, Eldridge plays these pieces very well, but neither matches the original recordings, and some choices seem arbitrary (such as the scatted opening cadenzas of “Rockin’ Chair”).

On April 23, the same quintet—save for Jo Jones replacing Heard—reconvened for another 4-title session. A fine medium-tempo version of “Love for Sale” with Eldridge in cup mute opened the proceedings. Jones’ brushes are the perfect background over Eldridge’s intense solo trumpet and Peterson’s increasing confident Hammond organ. “Oscar’s Arrangement” (but Eldridge’s composition) sounds like “Five O’Clock Whistle”, but the highly-energized trumpet solo—with Kessel finally emerging as a complementary duet partner—and a shouting big-band style out-chorus turns this piece into an excellent showcase. “The Man I Love” is one of Eldridge’s finest ballad recordings. Without making major changes in George Gershwin’s original phrase lengths, Eldridge makes this tune his own by carefully adding and substituting his own note choices in between and on top of Gershwin’s melody. Again, his gorgeous open tone grabs our attention, as the rest of the group focuses on supporting Eldridge’s eloquent statement.

“Dale’s Wail” is the kind of blues that can generally be captured without a lot of alternate takes. But as on Charlie Parker’s “Parker’s Mood”, the musicians felt that they could improve upon it with another take. Placed as the second selection in the session, take 5 of “Dale’s Wail” was the first complete take. Eldridge starts with an unaccompanied kick-off on Harmon-muted horn, rhythm (sans organ) join in on the first chorus. The full rhythm section appears in the next chorus as Eldridge begins to build the intensity of his ideas and rise to the top register of the horn. Peterson’s organ sounds like a big-band horn section in support of the solo trumpet. As the solo reaches its climactic choruses, Eldridge adds a recurring idea in the form of a syncopated held note. It is as if he is shouting, “WAAAIIITT! I’m not done yet!”. In retrospect, this take should have ended a chorus earlier, as Eldridge is clearly running out of gas, and his trumpet goes on-and-off mike, making it hard to hear him over the organ. On the other hand, those may have been the very reasons the musicians used to convince Granz to try it again. So, after the triumphs of “The Man I Love” and “Oscar’s Arrangement”, they went back to the blues. Take 10 is a touch faster and a little more skittish. Unlike take 5, there is not an abrupt jump in intensity midway through the track. Eldridge stays on mike and he has more energy left at the end. “So, that’s it, right?” “No, not quite. Let’s try again.” Take 12 goes back to the original tempo. In comparison to the earlier two takes, the energy is noticeably lower—but standing on its own, it sounds fine. The overall crescendo works well, and Eldridge uses the held high note again to accentuate the final choruses. Someone still believes that there’s a better take yet to come, so Granz agrees to one more try. Take 13, in roughly the same tempo, finds Eldridge taking a methodical approach to the early choruses and saving a little more strength for the finale. The held notes return at the end and it seems that all issues have been worked out. Take 13 was picked as the master…and sometime before the recording was released, someone—probably Granz—decided that take 5 was better after all, and that take became the master. It’s hard to call any of these takes the standout version, but it is interesting that this recording, which is widely considered to be Eldridge’s masterpiece, uses the take with the most obvious musical and technical problems!

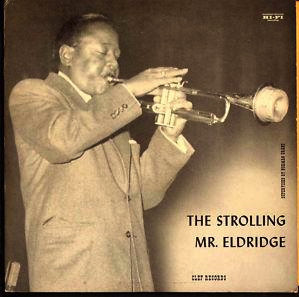

By the time of the third session, recorded in Los Angeles on December 10, 1953, Barney Kessel had left the Peterson Trio, and was replaced by Herb Ellis. Peterson was back on piano, and Alvin Stoller was the drummer. While the individual titles were issued on singles, the focus was now on the 10” LP, eventually titled, “The Strolling Mr. Eldridge”. There was also an attempt to produce a mellower album than the previous recordings. Eldridge seems agreeable to the ballad concept, but his version of “Willow Weep for Me” lacks the authoritative punch of “The Man I Love”. The “stroll” of the album title (which was Eldridge’s term for improvising with just bass and drums in accompaniment makes a very brief appearance in the intro to “Somebody Loves Me”. Otherwise, the tune yields a gruff, growling trumpet solo in medium tempo. “When Your Lover Has Gone” spotlights Eldridge’s open horn with subtle encouragement from Stoller in the final chorus. The ideas flow well, and Eldridge’s three choruses tell a definite story. Louis Armstrong’s theme song, “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” survives in two takes. Eldridge gets a better start on the master but loses focus near the end of the track. There’s a minor fluff early in the alternate, but the solo falls together better on the alternate. (I’m glad Mosaic saved this one from the vault!) “Feeling a Draft”, based on “Love Me or Leave Me”, is the standout track from this session. Stoller’s drums wake everyone up, and Eldridge digs into the minor groove. His melodically rich solo is enhanced with a background riff developed on the spot by Peterson and Ellis. Eldridge’s chops needed a break, and the version of “Don’t Blame Me” that came next shows that he didn’t get one! There are several muffed notes early on, and while Eldridge is trying to give his all, it’s a little more than he can handle. Growl trumpet takes a lot of stamina, and Eldridge sounds a little rested on the two takes of “Echoes of Harlem” (a Cootie Williams feature from the Duke Ellington book). On the master, Brown and Peterson meld well on the loping ostinato part, Ellis adds a few blues licks, and Eldridge gets a relaxed sound during the middle section of the piece. The 10” LP master is noticeably slower and is less successful because of it. The session ends with a tender version of an Eldridge favorite, “I Can’t Get Started”.

the 10” LP, eventually titled, “The Strolling Mr. Eldridge”. There was also an attempt to produce a mellower album than the previous recordings. Eldridge seems agreeable to the ballad concept, but his version of “Willow Weep for Me” lacks the authoritative punch of “The Man I Love”. The “stroll” of the album title (which was Eldridge’s term for improvising with just bass and drums in accompaniment makes a very brief appearance in the intro to “Somebody Loves Me”. Otherwise, the tune yields a gruff, growling trumpet solo in medium tempo. “When Your Lover Has Gone” spotlights Eldridge’s open horn with subtle encouragement from Stoller in the final chorus. The ideas flow well, and Eldridge’s three choruses tell a definite story. Louis Armstrong’s theme song, “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” survives in two takes. Eldridge gets a better start on the master but loses focus near the end of the track. There’s a minor fluff early in the alternate, but the solo falls together better on the alternate. (I’m glad Mosaic saved this one from the vault!) “Feeling a Draft”, based on “Love Me or Leave Me”, is the standout track from this session. Stoller’s drums wake everyone up, and Eldridge digs into the minor groove. His melodically rich solo is enhanced with a background riff developed on the spot by Peterson and Ellis. Eldridge’s chops needed a break, and the version of “Don’t Blame Me” that came next shows that he didn’t get one! There are several muffed notes early on, and while Eldridge is trying to give his all, it’s a little more than he can handle. Growl trumpet takes a lot of stamina, and Eldridge sounds a little rested on the two takes of “Echoes of Harlem” (a Cootie Williams feature from the Duke Ellington book). On the master, Brown and Peterson meld well on the loping ostinato part, Ellis adds a few blues licks, and Eldridge gets a relaxed sound during the middle section of the piece. The 10” LP master is noticeably slower and is less successful because of it. The session ends with a tender version of an Eldridge favorite, “I Can’t Get Started”.

The final session took place in New York on September 15, 1954, with Buddy Rich in the drum chair. The tunes are noticeably longer as the goal is now a 12” LP. The playlist includes several gems from the Great American Songbook, and Eldridge now shares the solo spotlight with Peterson. Gershwin starts the program with a medium-tempo “A Foggy Day”. The Peterson Trio plus Rich set up a fine walking groove and for once, Eldridge is satisfied to ride with the groove instead of fighting it. Peterson, always excellent in this tempo, plays a delightful single-line solo before ushering Eldridge in for the final chorus. “Blue Moon” finds the leader with Harmon mute playing Richard Rodgers’ melody tenuously before adding a little more strength for his improvisation. Harold Arlen’s “Stormy Weather” opens with a duet for Harmon muted trumpet and brushes on snare, but Eldridge quickly pulls the mute to play the song with his rich open tone. When he moves into his solo, Eldridge creates a magnificent statement full of contrasting emotions. On another of Louis Armstrong’s anthems, “Sweethearts on Parade”, Eldridge tips his hat (and plays into it!) This tribute also includes another fine Peterson solo in a grooving medium tempo. “If I Had You” is a beautiful song, aptly caressed by Eldridge and the band. Apart from one small misstep—an overplayed entrance—this recording is a stunning version of a great standard. Harry Warren’s “I Only Have Eyes for You” stretches to over seven minutes. Eldridge’s raspy tone simply accentuates his lines as he happily navigates the lovely changes. Peterson sparkles through his two choruses before Eldridge ends the tune with a dramatic flourish…which somehow extends for another chorus! What is marked as “Sweet Georgia Brown” is actually an Eldridge original called “The Gasser”—and that it is. The tempo flies, with both Eldridge and Peterson gobbling up notes as fast as they can. Then Eldridge pulls the mute and jumps to the high register, with Rich providing all of the extra fuel. There’s a quick set of four-bar exchanges between drums and trumpet before Eldridge stuffs in the mute for an uncharacteristic quiet coda. The session and the set close with an easy-going take on Irving Berlin’s “The Song is Ended (But The Melody Lingers On)”.

American Songbook, and Eldridge now shares the solo spotlight with Peterson. Gershwin starts the program with a medium-tempo “A Foggy Day”. The Peterson Trio plus Rich set up a fine walking groove and for once, Eldridge is satisfied to ride with the groove instead of fighting it. Peterson, always excellent in this tempo, plays a delightful single-line solo before ushering Eldridge in for the final chorus. “Blue Moon” finds the leader with Harmon mute playing Richard Rodgers’ melody tenuously before adding a little more strength for his improvisation. Harold Arlen’s “Stormy Weather” opens with a duet for Harmon muted trumpet and brushes on snare, but Eldridge quickly pulls the mute to play the song with his rich open tone. When he moves into his solo, Eldridge creates a magnificent statement full of contrasting emotions. On another of Louis Armstrong’s anthems, “Sweethearts on Parade”, Eldridge tips his hat (and plays into it!) This tribute also includes another fine Peterson solo in a grooving medium tempo. “If I Had You” is a beautiful song, aptly caressed by Eldridge and the band. Apart from one small misstep—an overplayed entrance—this recording is a stunning version of a great standard. Harry Warren’s “I Only Have Eyes for You” stretches to over seven minutes. Eldridge’s raspy tone simply accentuates his lines as he happily navigates the lovely changes. Peterson sparkles through his two choruses before Eldridge ends the tune with a dramatic flourish…which somehow extends for another chorus! What is marked as “Sweet Georgia Brown” is actually an Eldridge original called “The Gasser”—and that it is. The tempo flies, with both Eldridge and Peterson gobbling up notes as fast as they can. Then Eldridge pulls the mute and jumps to the high register, with Rich providing all of the extra fuel. There’s a quick set of four-bar exchanges between drums and trumpet before Eldridge stuffs in the mute for an uncharacteristic quiet coda. The session and the set close with an easy-going take on Irving Berlin’s “The Song is Ended (But The Melody Lingers On)”.

Roy Eldridge recorded for labels other than Granz’s Clef, Verve, Down Home, and Pablo, but there is little doubt that Granz’s patronage helped establish Eldridge as one of jazz’s greatest trumpeters, rather than just the “link between Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie”. In fact, Granz said as much himself to John S. Wilson of “The New York Times”: I feel like I have a certain responsibility to jazz and certain jazz musicians that have made me successful—some who have been passed by—such as Roy Eldridge, [Count] Basie and the rest. From a recording standpoint, nothing much was being done for them. Granz’s Pablo label brought several of his favorite artists back into the recording studios, working for a man who cared more about capturing great music than making hit records. When Eldridge died in 1989 (just three weeks after the death of Eldridge’s longtime wife, Vi), Granz picked up the costs for the trumpeter’s funeral. And that is the definition of a great friend.