Starting in 1945, Los Angeles was a hotbed of bebop. While Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were recording their classic Guild and Musicraft sides in New York, Coleman Hawkins was in LA with a modernist band including Howard McGhee and Sir Charles Thompson. By the end of the year, Parker and Gillespie traveled west for a gig at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood. Parker stayed behind after the rest of the band went home. Following a disastrous breakdown and temporary cure for his heroin habit, he recorded with McGhee, Wardell Gray, Erroll Garner and Dodo Marmarosa before returning east. Meanwhile, in the clubs along Central Avenue, jam sessions featuring McGhee, Gray, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Criss and Hampton Hawes had the audiences cheering on their favorite players. Within a few years, the scene waned, and many of the clubs either closed or were converted into strip joints. The primary musicians went on tours with major bands or were off the scene because of drug addictions. By 1952, through the successes of Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Shorty Rogers, Bud Shank, Bob Cooper, Howard Rumsey, Shelly Manne and others, California jazz was generally synonymous with cool jazz.

Starting in 1945, Los Angeles was a hotbed of bebop. While Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were recording their classic Guild and Musicraft sides in New York, Coleman Hawkins was in LA with a modernist band including Howard McGhee and Sir Charles Thompson. By the end of the year, Parker and Gillespie traveled west for a gig at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood. Parker stayed behind after the rest of the band went home. Following a disastrous breakdown and temporary cure for his heroin habit, he recorded with McGhee, Wardell Gray, Erroll Garner and Dodo Marmarosa before returning east. Meanwhile, in the clubs along Central Avenue, jam sessions featuring McGhee, Gray, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Criss and Hampton Hawes had the audiences cheering on their favorite players. Within a few years, the scene waned, and many of the clubs either closed or were converted into strip joints. The primary musicians went on tours with major bands or were off the scene because of drug addictions. By 1952, through the successes of Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Shorty Rogers, Bud Shank, Bob Cooper, Howard Rumsey, Shelly Manne and others, California jazz was generally synonymous with cool jazz.

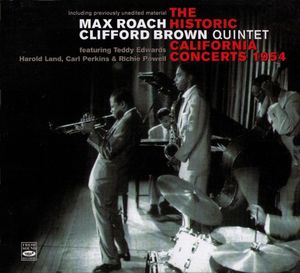

When Manne left Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars to join Rogers’ new cool quintet, he recommended Max Roach to fill his position. Roach and Manne had been friends since their days in New York, and Roach had played the cool style in broadcasts and recordings with Miles Davis and Lee Konitz. During his six months with the Lighthouse group, Roach created a local sensation with his drumming, and played on several live Lighthouse recordings as well as studio sessions like the Cooper/Shank LP, “Oboe/Flute”. The California gig allowed Roach to show his adaptability, but he never stopped listening to the harder-edged music from New York, including Art Blakey’s “A Night at Birdland” and “The Eminent J.J. Johnson”. Both of those albums featured a remarkable young trumpeter named Clifford Brown. When Brown arrived on the scene in 1953, he seemed to be just what jazz needed: an imaginative young trumpeter with a full brilliant sound and remarkable technical prowess. Those who knew him personally also praised his sunny disposition and his aversion to alcohol, tobacco and narcotics. As Roach’s Lighthouse contract was ending, concert promoter Gene Norman talked to the drummer about forming his own group. Roach agreed—provided that Norman would give them gigs to play—and immediately sought out Brown to be his co-leader. Norman was good to his word, providing a long-standing engagement at Pasadena’s California Club, and setting up a West Coast tour. He also featured the Brown/Roach Quintet in concerts at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium and LA’s Shrine Auditorium. Those concerts were recorded and later issued on Norman’s GNP label, but their best presentation is on the Fresh Sound CD “Historic California Concerts”, which restores the recordings to their full length and improves the sound.

The Pasadena concert was recorded in April 1954. The band had only been in existence for about two months, but had already played a few weeks at the California Club. The fine and under-rated tenor saxophonist Teddy Edwards shares the front line with Brown. The piano chair was filled by Carl Perkins—not the “Blue Suede Shoes” singer, of course, but a bopper who played with his left arm parallel to the keybo ard (owing to a battle with polio). The bassist was the steady but unremarkable George Bledsoe. None of the pieces recorded in Pasadena found a place in the group’s permanent repertoire, but the performances are spirited and the audience clearly appreciated the energy of this driving bebop group. After an introduction featuring brief solos by each member of the group (omitted from the GNP 12” LP), the group launches into a medium-up version of “All God’s Children Got Rhythm”. Edwards starts the solos with a beefy tenor solo that is abruptly cut off after one chorus. Brown is next and Roach’s ongoing rhythmic commentary spurs the trumpeter through a brilliant extended solo. Perkins’ fleet piano is also cut off after one chorus (these edits were on all previous editions and could not be restored for the CD), but Roach’s complex drum solo is kept intact. Gillespie’s strong influence on Brown can be heard in the opening phrases of Brown’s ballad feature, “Tenderly”, but one can also hear the subtle half-valved effects and the fluidity in all ranges of the horn that became part of his mature style. “Sunset Eyes” predicts the group’s use of tidy and effective arrangements. The A sections of Edwards’ composition feature a sensuous tune over a single chord, and the bridge has an exuberant melody over a standard ii-V-I bebop progression. Edwards also wrote an out-chorus over the A section. On the final chorus of the Brown/Roach arrangement, the band plays 16 bars of the out-chorus, then jumps back to the bridge and closes with 8 bars of the original A section. The syncopated pick-up to the bridge gives a dramatic lift to the arrangement, and it’s surprising that Edwards never used this arrangement in his own recordings. Edwards plays a fine solo here, and both he and Brownie explore the harmonic contrasts between the main strain and the release. Edwards lays out on the last track, “Clifford’s Axe”, which is a relaxed long-meter jam on the changes of “The Man I Love”. The masterly sculpting of his improvised lines and the steady pacing of the solo belies Brown’s age (23), and the interplay with Roach—which would develop to amazing heights over the next two years—is already quite stunning.

ard (owing to a battle with polio). The bassist was the steady but unremarkable George Bledsoe. None of the pieces recorded in Pasadena found a place in the group’s permanent repertoire, but the performances are spirited and the audience clearly appreciated the energy of this driving bebop group. After an introduction featuring brief solos by each member of the group (omitted from the GNP 12” LP), the group launches into a medium-up version of “All God’s Children Got Rhythm”. Edwards starts the solos with a beefy tenor solo that is abruptly cut off after one chorus. Brown is next and Roach’s ongoing rhythmic commentary spurs the trumpeter through a brilliant extended solo. Perkins’ fleet piano is also cut off after one chorus (these edits were on all previous editions and could not be restored for the CD), but Roach’s complex drum solo is kept intact. Gillespie’s strong influence on Brown can be heard in the opening phrases of Brown’s ballad feature, “Tenderly”, but one can also hear the subtle half-valved effects and the fluidity in all ranges of the horn that became part of his mature style. “Sunset Eyes” predicts the group’s use of tidy and effective arrangements. The A sections of Edwards’ composition feature a sensuous tune over a single chord, and the bridge has an exuberant melody over a standard ii-V-I bebop progression. Edwards also wrote an out-chorus over the A section. On the final chorus of the Brown/Roach arrangement, the band plays 16 bars of the out-chorus, then jumps back to the bridge and closes with 8 bars of the original A section. The syncopated pick-up to the bridge gives a dramatic lift to the arrangement, and it’s surprising that Edwards never used this arrangement in his own recordings. Edwards plays a fine solo here, and both he and Brownie explore the harmonic contrasts between the main strain and the release. Edwards lays out on the last track, “Clifford’s Axe”, which is a relaxed long-meter jam on the changes of “The Man I Love”. The masterly sculpting of his improvised lines and the steady pacing of the solo belies Brown’s age (23), and the interplay with Roach—which would develop to amazing heights over the next two years—is already quite stunning.

By August 30, when the group performed at the Shrine, the personnel had stabilized to include Harold Land on tenor, Richie Powell on piano and George Morrow on bass. The band had abundantly recorded in the intervening months, including its own debut album for EmArcy, and studio jam sessions featuring Dinah Washington, Maynard Ferguson, Clark Terry, Herb Geller, Walter Benton and Curtis Counce. Just how Gene Norman  obtained the rights to record the already-contracted Brown and Roach at the Shrine has never been fully explained, but the recording offers one of the earliest examples of this group in a live context. Three of the four songs from that night had been recorded by the quintet for EmArcy earlier in the month, and the group seems very comfortable with the tunes and the arrangements. “Jordu” features relaxed solos by both Brown and Land, with both soloists effectively punctuating their lines with sharp rhythmic motives. Powell tries to spice up his solo with a few quotes, but he was still an immature player and a mere shadow of his brother Bud. Roach astonishes with another brilliant display of polyrhythmic expertise (Land and Powell’s solos only appear on the GNP 10” LPs and on the Fresh Sounds CD). Brown’s ballad feature this time is “I Can’t Get Started”, a tune which he never recorded again. This version is hampered by PA feedback that distorts Brown’s rich trumpet sound. A pity, since this is one of Brownie’s most understated ballad performances. Next up is the band’s tricky mixed-meter version of “I Get a Kick out Of You” (arranged by either Sonny Stitt or Thad Jones). Roach sets an extremely bright tempo, but Brown sounds quite comfortable playing at this quick pace, laying out long phrases over several bars. Land is a little more frantic, but generates a lot of excitement. Powell tries to mix the approaches of the horn men, but his underdeveloped melodic imagination makes the effort sound disorganized and chaotic. Roach’s solo brings things back to normal with a dense thunder of percussion. The final track is Bud Powell’s “Parisian Thoroughfare”, complete with instrumental imitations of a French traffic jam. While the opening is at an even faster tempo than “Kick”, it settles into a medium-up groove for the melody and solos. Land’s sound is as warm as a wool jacket, and his off-hand quote of Offenbach’s can-can theme works very well. Brown is wonderfully melodic in his solo, and the legato in his tone seems to reflect Roach’s smooth ride cymbals in the background.

obtained the rights to record the already-contracted Brown and Roach at the Shrine has never been fully explained, but the recording offers one of the earliest examples of this group in a live context. Three of the four songs from that night had been recorded by the quintet for EmArcy earlier in the month, and the group seems very comfortable with the tunes and the arrangements. “Jordu” features relaxed solos by both Brown and Land, with both soloists effectively punctuating their lines with sharp rhythmic motives. Powell tries to spice up his solo with a few quotes, but he was still an immature player and a mere shadow of his brother Bud. Roach astonishes with another brilliant display of polyrhythmic expertise (Land and Powell’s solos only appear on the GNP 10” LPs and on the Fresh Sounds CD). Brown’s ballad feature this time is “I Can’t Get Started”, a tune which he never recorded again. This version is hampered by PA feedback that distorts Brown’s rich trumpet sound. A pity, since this is one of Brownie’s most understated ballad performances. Next up is the band’s tricky mixed-meter version of “I Get a Kick out Of You” (arranged by either Sonny Stitt or Thad Jones). Roach sets an extremely bright tempo, but Brown sounds quite comfortable playing at this quick pace, laying out long phrases over several bars. Land is a little more frantic, but generates a lot of excitement. Powell tries to mix the approaches of the horn men, but his underdeveloped melodic imagination makes the effort sound disorganized and chaotic. Roach’s solo brings things back to normal with a dense thunder of percussion. The final track is Bud Powell’s “Parisian Thoroughfare”, complete with instrumental imitations of a French traffic jam. While the opening is at an even faster tempo than “Kick”, it settles into a medium-up groove for the melody and solos. Land’s sound is as warm as a wool jacket, and his off-hand quote of Offenbach’s can-can theme works very well. Brown is wonderfully melodic in his solo, and the legato in his tone seems to reflect Roach’s smooth ride cymbals in the background.

Soon after the Shrine concert, the Brown/Roach quintet relocated on the East Coast, but its formative months on the West Coast helped revitalize California’s modern jazz scene. Within a year, a steady stream of hard-edged bebop emerged from the West Coast. When Harold Land left Brown/Roach in late 1955, he joined the Curtis Counce Group, which became one of the finest bop groups in LA. Both Land and Teddy Edwards remained important players on the LA jazz scene for the rest of their lives, and they played together in the Gerald Wilson big band. Carl Perkins was an early member of the Counce Group, but died of a drug overdose in 1958. Sonny Rollins replaced Land in the Brown/Roach quintet, and the resulting chemistry made the group one of the finest exponents of the bebop style. It all ended tragically when Brown, Powell and Powell’s wife died in an automobile accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike on June 26, 1956. It took Roach several years to fully recover, but eventually he came back with a powerful new group (ironically featuring another short-lived trumpeter, Booker Little) that recorded classic albums like “Freedom Now Suite” and “Percussion Bitter Sweet”. Had Clifford Brown survived the accident, he would have been in his mid-eighties by now. Heaven only knows what directions he would have taken had his career not been cut off in his twenty-fifth year. Like JFK, the youth of Clifford Brown is locked forever in a time capsule, and the hope and optimism he personified will forever be linked with the sorrow of his early demise.