At 25 years old, Veronica Swift has built an impressive résumé: a professional singer since the age of 9, featured performer at Jazz at Lincoln Center since 2005, leader of four albums starting when she was 10, a 2015 second place finalist in the Thelonious Monk Jazz Competition, headliner at the Telluride Jazz Festival since 2016 (with several performances there in previous years), a 2017 residency at Birdland in New York City, plus recurring performances with the Birdland Big Band, Chris Botti, Benny Green and Wynton Marsalis. She exhibits remarkable poise when singing selections from the Great American Songbook, has a deep and abiding knowledge of jazz styles from traditional to progressive, is a skilled author of vocalese lyrics, and is one of the most harmonically astute scat singers working today. And while her spoken introduction in the video below exudes great humility of working with experienced jazz musicians like Marsalis, her ensuing performance shows that she creates at the same level as her esteemed colleagues.

Swift comes from great stock. As stated in the video, her father was the gifted bop pianist and composer Hod O’Brien. Her mother is the equally celebrated vocalist Stephanie Nakasian. Swift’s stage name descended from the surname of O’Brien’s birth mother, which the family discovered just as Veronica decided to become a professional vocalist. Swift’s earliest musical memories revolve around classical music and an iconic jazz singer: When I was 4 years old, Mom would put on Bach before I went to bed. I remember that being my first love. I couldn’t go to sleep when I was listening to the Harpsichord Concerto in D Minor. I’d sing along with it—all three movements—and then I’d say “OK, now I can go to sleep”! When I was five, I heard Bobby McFerrin sing the Bach Inventions and I thought “Wow! He’s so in tune” and decided that I wanted to sing like that—in tune and in the center of each note.

Swift shared the gift of perfect pitch with her father, and while she finds the benefits useful today—she never requires a starting pitch—it doesn’t bother her when she hears something out of tune, noting that one of her favorite singers, June Christy, typically sang just under the pitch. As a child, she came along to her parents’ gigs, usually sitting backstage working on a coloring book or napping in the string bass case. After her parents recognized her talent, Swift was brought on stage to sing with the band. She attended public school, played trumpet in the school band, sang in the choir, and took private piano lessons. She states that most of her education came from her school teachers, and that her parents only suggested recordings for her to hear before gigs, rather than giving her lessons in harmony or technique (Nakasian even told me that she wasn’t completely sure that her daughter should pursue a performing career!)

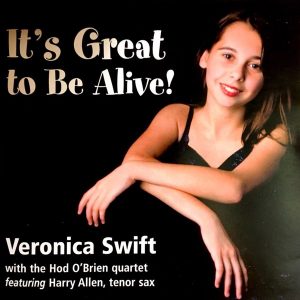

Swift’s first albums were “Veronica’s House of Jazz” and “It’s Good to Be Alive!”, both issued on her parents’ record label HodStef. In addition to her parents, her accompanists included Richie Cole (“House”) and Harry Allen (“Alive”). When asked about these recordings, she said: I think I was hipper back then than I am now! When you’re a kid, you have no bad habits, and no inhibitions. It’s pure! [It’s] singing for the sake of singing, and that’s what we strive for as developed artists. It’s hard to get back to that point. Listening back, I think my scat solos are really imaginative and hip! I really love them!

Swift’s first albums were “Veronica’s House of Jazz” and “It’s Good to Be Alive!”, both issued on her parents’ record label HodStef. In addition to her parents, her accompanists included Richie Cole (“House”) and Harry Allen (“Alive”). When asked about these recordings, she said: I think I was hipper back then than I am now! When you’re a kid, you have no bad habits, and no inhibitions. It’s pure! [It’s] singing for the sake of singing, and that’s what we strive for as developed artists. It’s hard to get back to that point. Listening back, I think my scat solos are really imaginative and hip! I really love them!

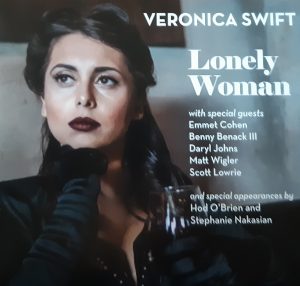

After graduating from high school, she earned a full-ride scholarship to the Frost School of Music in Miami. Under the tutelage of Shelley Berg and other faculty members, Swift developed into a world-class vocalist. There are several videos on YouTube of Swift performing between 2013 and 2016, but her most polished effort remains her 2015 CD “Lonely Woman”. Using a rotating group of sidemen (including her father, on what would be his final  recordings) Swift performs a wide range of jazz and pop standards with extraordinary sensitivity. The title track, composed by Benny Carter, is a gorgeous duet featuring Swift and pianist Emmet Cohen. Swift’s voice has a deep magenta hue, and her phrasing reflects her profound understanding of the mournful lyric. A rendition of “September in the Rain” featuring O’Brien includes Swift’s impressive vocalese setting of a Lester Young solo, while “Swaggin’ Like Me” (co-composed by Swift and pianist Matt Wigler) includes another Swift vocalese, this one set to a 2009 solo by Wigler—who also plays on the 2015 version! One of two tracks recorded in 2013, a swinging version of “You Don’t Know What Love Is” features an astounding scat solo where Swift creates a push-pull effect by phrasing against the band’s ground beat, all the while displaying her phenomenal vocal range. While in Florida, she also worked with the Stan Getz-inspired tenor saxophonist Jeff Rupert, and on a 2017 CD called “Let’s Sail Away”, Swift acts as the band’s second horn, singing lyrics where available, but otherwise scatting her parts in the ensemble and contributing several fine scat solos.

recordings) Swift performs a wide range of jazz and pop standards with extraordinary sensitivity. The title track, composed by Benny Carter, is a gorgeous duet featuring Swift and pianist Emmet Cohen. Swift’s voice has a deep magenta hue, and her phrasing reflects her profound understanding of the mournful lyric. A rendition of “September in the Rain” featuring O’Brien includes Swift’s impressive vocalese setting of a Lester Young solo, while “Swaggin’ Like Me” (co-composed by Swift and pianist Matt Wigler) includes another Swift vocalese, this one set to a 2009 solo by Wigler—who also plays on the 2015 version! One of two tracks recorded in 2013, a swinging version of “You Don’t Know What Love Is” features an astounding scat solo where Swift creates a push-pull effect by phrasing against the band’s ground beat, all the while displaying her phenomenal vocal range. While in Florida, she also worked with the Stan Getz-inspired tenor saxophonist Jeff Rupert, and on a 2017 CD called “Let’s Sail Away”, Swift acts as the band’s second horn, singing lyrics where available, but otherwise scatting her parts in the ensemble and contributing several fine scat solos.

As Swift was completing her degree at Frost, Hod O’Brien was diagnosed with cancer. The anxiety of losing her beloved father along with a general frustration over her education temporarily led Swift away from jazz. She was always interested in industrial rock and opera, and at the time, she felt that jazz could not fully express her emotions. She met Marilyn Manson, and was inspired to compose her own three-act rock opera, “Vera Icon”. The work was presented in Miami and New Orleans with Swift’s own rock band featured prominently. Swift hopes to re-stage the opera in New York sometime in the next few years. She also plans to include the Queen anthem “Innuendo” on a future recording.

In the past few years, Swift has refocused her energies on jazz. She tours all over the world, performing with some of the biggest names in the music. Her recent recording with Benny Green, “Then and Now” (reviewed here) introduced Swift to several new fans—including this writer—and Green’s trio is one of two (the other led by Emmet Cohen) which accompany Swift on her latest album, “Confessions”. Swift and Green have worked together for years, and the following video from this year’s Umbria Jazz Festival shows the vocalist and the band bouncing ideas back and forth with abandon.

With the above videos (and many more available recordings) in mind, Swift’s major label debut, the aforementioned “Confessions” may surprise many of her fans (Swift takes this all in stride, quipping If I don’t surprise people, I haven’t done my job). While the album opens with the confident anthem “You’re Gonna Hear from Me”, Swift’s arrangement carries less swagger than Frank Sinatra’s famous recording. There is only one extended scat solo on the entire album, and many of the songs reflect tragic events from Swift’s recent past, including her father’s death and a calamitous house fire. She elaborates: It’s all about story and context. This is a pure representation of where I was over the last two years. It seemed forced to put  on scat and vocalese tracks on the new album, just because people expected them. There’s never a dull moment in my life. Some people see my young face, and they don’t understand what has gone into making my artistry what it is. I’m not putting myself on a pedestal, but it’s good for people to know that loss is something that’s big and following me a lot. But I’m grateful for these experiences because they let me create the way I do.

on scat and vocalese tracks on the new album, just because people expected them. There’s never a dull moment in my life. Some people see my young face, and they don’t understand what has gone into making my artistry what it is. I’m not putting myself on a pedestal, but it’s good for people to know that loss is something that’s big and following me a lot. But I’m grateful for these experiences because they let me create the way I do.

While listeners can probably fill in the blanks regarding Swift’s personal troubles, the value of the album comes from the intensity of Swift’s performances, and her superb small-group arrangements which incorporate a wide range of stylistic and tempo shifts. Her stunning version of Pete Rugolo’s “Interlude” reveals subtle gradations of volume over a hypnotic background. Swift embodies the enigmatic lyrics with deep understanding of their multi-leveled meaning, bringing new life to this unfairly neglected song. “Forget About the Boy” was revived from the Broadway musical “Thoroughly Modern Millie”, and Swift employs a little dramaticism in the verse. When the group moves into the chorus, Swift and the Cohen trio effortlessly navigate the arrangement, which travels through medium swing, Latin and up-tempo bop before the dramatic coda. One of the album’s highlights is the medley of Mel Tormé’s “A Stranger in Town” and Victor Schertzinger’s “I Don’t Want to Cry Any More”. The contrast between Swift’s dead-slow and mournful reading of the Tormé song with the bright-tempoed determination of Schertzinger’s standard not only works on a purely musical level, it also connects two sides of the same story. Swift accomplishes the same feat later on the disc when she combines the previously light-hearted Howard Dietz/Arthur Schwartz song “Confession” with Nina Simone’s tragic “The Other Woman”. For those who crave a sample of Swift’s outstanding ballad style, below is her live recording of a wonderfully crafted love song by Kenneth Laub, “You Again” (which Swift hopes to release as a single in the near future).

Naturallly, Swift’s current live performances include many of the songs from “Confession”, but she mixes in songs from previous albums and possible candidates for her next discs (Currently, Swift has tentative plans for four full-length CDs, including an album of her father’s originals). When Swift performed with the Emmet Cohen Trio at the 2019 Vail Jazz Festival, she wowed the audience with a program filled with familiar standards, sumptuous ballads, thrilling scat solos, and a rousing tribute to James P. Johnson. She opened with two comic songs, a heavily sarcastic rendition of “How Lovely to Be a Woman” (from “Bye Bye, Birdie”) and Dave Frishberg’s “A Little Taste” (with Swift’s facial expressions bringing out the humor of the lyric), and then followed with the dramatic “Interlude”. Such programming can be quite risky, but the juxtaposition worked brilliantly. A new arrangement of “Money, Money” from “Cabaret” featured a menacing vamp leading to up- and down-tempo Latin sections. Swift made appropriate changes to the lyrics to the verse of “Someone to Watch Over Me” and to Oscar Brown, Jr.’s “Dat Dere”—transforming the latter into a song about an unfaithful lover. Later, she engaged bassist Phil Kuehn in a swinging duet on Oscar Pettiford’s “Tricotism”, and the show finished with a lightning-fast reading of “Tea for Two”, performed in the style of another Swift inspiration, Anita O’Day.

with Emmet Cohen (piano), Phil Kuehn (bass) and Kyle Poole (drums).

Veronica Swift is still a developing artist. Currently, her interpretations bear the stamp of June Christy and Anita O’Day, but those influences will certainly meld into her individual style in the same way that Swift has absorbed another primary influence, Ella Fitzgerald. Anyone who has seen Swift in videos or in person has doubtlessly noticed her highly varied clothing styles, encompassing goth, elegance, bohemian, and even cross-dressing. In some ways, her diverse clothing reflects her multi-faceted tastes in music, but if she ever needed a secondary career, she could probably work as a fashion model. Obviously, we don’t know the directions Swift’s music will take in the coming years, but we can take some comfort in her own summation: I don’t have any fame-related ambitions. I go where the music takes me and I’ll speak to whoever’s listening.

Speak and sing well, young lady. The world is listening.

The sub-title of this article is a partial quote from Shakespeare’s “Antony and Cleopatra”: “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale, her infinite variety”.

Cover photo and Vail concert photo by Steven Pope, Talking Rock Photography.

Thanks for Veronica Swift, Emmet Cohen, Stephanie Nakasian, James Kenly and the staff of the Vail Jazz Festival.

The video recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.