The recordings of Tubby Hayes can be split into four distinct categories:

1) Tempo Records (1955-1959), where Hayes made his first dates as a leader, recorded several subsequent albums (on his own and with others) and recorded a series of albums with the renowned two-tenor band, The Jazz Couriers (co-lead by Ronnie Scott).

2) Fontana Records (1961-1969), including Hayes’ mature period where he moved from straight-ahead big band and bebop into the progressive areas of 1960s avant-garde jazz.

3) Sideman dates (1951-1973), starting with the tenor man’s first recordings—made while he was still a teenager—to his final known recordings made under the leadership of trumpeter Ian Hamer.

4) Live/broadcast dates (1954-1972), a burgeoning set of private recordings which seems to grow every year, with newly discovered tapes issued on a regular basis.

Thankfully, the recordings from categories 1, 3 and 4—especially those recorded before 1962—have been extensively reissued, thanks to the public domain laws in the UK and Europe. In contrast, Fontana’s Hayes recordings  fell out of print during the saxophonist’s lifetime, and attempts to reissue the complete Hayes Fontana albums have been hobbled by fits and starts, with several albums remaining unavailable since their original releases. With the success of the recently discovered and issued 1969 Hayes quartet sessions, “Grits, Beans and Greens”, Universal Music has finally assembled a lovingly remastered 13-CD set, “The Complete Fontana Albums”, which also includes previously unissued tracks and rarities. A consequent 11-LP set, “The Fontana Recordings” offers new editions of the original albums without extras. In addition to the music, both sets include extensive liner notes by Hayes’ expert Simon Spillett, which cover valuable background information on the music.

fell out of print during the saxophonist’s lifetime, and attempts to reissue the complete Hayes Fontana albums have been hobbled by fits and starts, with several albums remaining unavailable since their original releases. With the success of the recently discovered and issued 1969 Hayes quartet sessions, “Grits, Beans and Greens”, Universal Music has finally assembled a lovingly remastered 13-CD set, “The Complete Fontana Albums”, which also includes previously unissued tracks and rarities. A consequent 11-LP set, “The Fontana Recordings” offers new editions of the original albums without extras. In addition to the music, both sets include extensive liner notes by Hayes’ expert Simon Spillett, which cover valuable background information on the music.

Hayes’ partnership with Fontana began after the collapse of Tempo Records, a company which barely had enough funds to maintain operations, despite its association with the British Decca label. Tempo’s chief producer, Tony Hall, had succeeded in licensing several Hayes recordings to American labels (including one album by the Jazz Couriers) but when it came to Hayes’ early masterpiece, “Tubby’s Groove”, Hall was unable to convince any US record company to release it. When Hall sent a collection of other tracks from the “Tubby’s Groove” session to Alfred Lion, the Blue Note president sequenced the tracks into an album, but never released the recording. Fontana—associated with the Dutch label, Philips—had deeper pockets and notably, a licensing deal which allowed albums from the US Columbia label to be issued under the Fontana imprint in the UK. When Hayes’ signed with the label, the deal became reciprocal, with two of Hayes’ Fontana albums being issued in the US on Columbia’s subsidiary label, Epic.

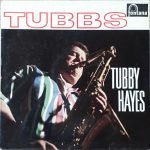

Hayes’ first album for Fontana was recorded in March 1961, and issued in the UK as “Tubbs” and in the US as “Introducing Tubbs”. While many US jazz  musicians knew about Hayes from the imported Tempo discs, this album was a splendid introduction to Hayes for the American jazz public. It featured Hayes in three settings: a brass-heavy big band with Johnny Scott’s piccolo covering the lead trumpet parts, a woodwind-and rhythm ensemble with Hayes featured on his primary double, vibraphone, and a session with his working quartet, featuring Terry Shannon (piano), Jeff Clyne (bass) and Bill Eyden (drums). The big band tracks featured thrilling tenor solos on “Love Walked In”, “Tubbsville” and “Cherokee” which displayed Hayes’ original style combining elements of Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz and Johnny Griffin. After his breathtaking run through the changes of “Cherokee”, Hayes tops himself with a spellbinding extended cadenza. Such bravura displays usually frustrated Hayes’ bandmates (mainly because they lacked Hayes’ technical prowess) but here, it proves to listeners that Hayes was every bit as good as advertised. The session with vibes and woodwinds produced a fine medium-tempoed version of “S’posin’” and the ballad “The Folks Who Live on the Hill”, which was singled out for praise by Rollins in a private conversation with Hayes. Ultimately, Hayes was at his best when playing with his quartet. “The Late One” burns with intensity from Eyden’s kick-off, and Hayes effortlessly spins out a brilliant solo at a ridiculously fast tempo. The soulful “RTH” (dedicated to Hayes’ infant son) features another astounding cadenza, which like the one on “Cherokee”, is clearly based on the tune’s original chord progression, rather than just a static chord. After a well-played version of “Falling in Love with Love”, the quartet launched into “Wonderful! Wonderful!” a pop tune previously recorded by Johnny Mathis, but notably covered by Rollins. Hayes’ ecstatic solo matches the song’s title, and here—as elsewhere in this session—the rhythm section of Shannon, Clyne and Eyden showed that they were able to work at Hayes’ high level both in maintaining grooves and as soloists.

musicians knew about Hayes from the imported Tempo discs, this album was a splendid introduction to Hayes for the American jazz public. It featured Hayes in three settings: a brass-heavy big band with Johnny Scott’s piccolo covering the lead trumpet parts, a woodwind-and rhythm ensemble with Hayes featured on his primary double, vibraphone, and a session with his working quartet, featuring Terry Shannon (piano), Jeff Clyne (bass) and Bill Eyden (drums). The big band tracks featured thrilling tenor solos on “Love Walked In”, “Tubbsville” and “Cherokee” which displayed Hayes’ original style combining elements of Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz and Johnny Griffin. After his breathtaking run through the changes of “Cherokee”, Hayes tops himself with a spellbinding extended cadenza. Such bravura displays usually frustrated Hayes’ bandmates (mainly because they lacked Hayes’ technical prowess) but here, it proves to listeners that Hayes was every bit as good as advertised. The session with vibes and woodwinds produced a fine medium-tempoed version of “S’posin’” and the ballad “The Folks Who Live on the Hill”, which was singled out for praise by Rollins in a private conversation with Hayes. Ultimately, Hayes was at his best when playing with his quartet. “The Late One” burns with intensity from Eyden’s kick-off, and Hayes effortlessly spins out a brilliant solo at a ridiculously fast tempo. The soulful “RTH” (dedicated to Hayes’ infant son) features another astounding cadenza, which like the one on “Cherokee”, is clearly based on the tune’s original chord progression, rather than just a static chord. After a well-played version of “Falling in Love with Love”, the quartet launched into “Wonderful! Wonderful!” a pop tune previously recorded by Johnny Mathis, but notably covered by Rollins. Hayes’ ecstatic solo matches the song’s title, and here—as elsewhere in this session—the rhythm section of Shannon, Clyne and Eyden showed that they were able to work at Hayes’ high level both in maintaining grooves and as soloists.

Just a week after finishing the “Tubbs” album, the quartet was recorded live at  the London Palladium. Charlie Parker’s “Ah-Leu-Cha” features several exciting exchanges between Hayes and Eyden, followed by fiery solos by tenor, piano and drums. Hayes switches to vibes for “Young and Foolish”, where he displays his subtle control of dynamics on the melody, and then improvises a solo notable for both its beauty and overall architecture. The quartet set closed with the blues “All Members”, and Hayes—back on tenor—swings mightily through a nine-chorus solo that barely dents his reserve of melodic ideas. While the solos for the rhythm section are shorter, each player acquits himself admirably in the spotlight. Hayes would form a new group in the following year, but this quartet was clearly one of his best. In August 1961, Hayes collaborated on an album with percussionist Jack Costanzo. Hayes used a pickup group for the two selections on which he was featured, and the complete personnel has never been recovered, although we know that trumpeter Jimmy Deuchar, tenor saxophonists Ronnie Scott and Tommy Whittle, and drummer Phil Seaman were present. “Penitentiary Breakout” sounds like a small-group track at the outset, but eventually reveals itself as a big band piece. Hayes, Deuchar and Seaman all provide fine blues solos on this medium-tempo track. Constanzo’s bongo drums introduce the Latin-flavored “Chase and Capture”, which features all three tenors (Hayes taking the center spot). These two sessions, along with an amiable 1963 single release of “Sally” and “I Believe in You” are all collected on a single CD in the box set—the only disc here to include material from more than one album.

the London Palladium. Charlie Parker’s “Ah-Leu-Cha” features several exciting exchanges between Hayes and Eyden, followed by fiery solos by tenor, piano and drums. Hayes switches to vibes for “Young and Foolish”, where he displays his subtle control of dynamics on the melody, and then improvises a solo notable for both its beauty and overall architecture. The quartet set closed with the blues “All Members”, and Hayes—back on tenor—swings mightily through a nine-chorus solo that barely dents his reserve of melodic ideas. While the solos for the rhythm section are shorter, each player acquits himself admirably in the spotlight. Hayes would form a new group in the following year, but this quartet was clearly one of his best. In August 1961, Hayes collaborated on an album with percussionist Jack Costanzo. Hayes used a pickup group for the two selections on which he was featured, and the complete personnel has never been recovered, although we know that trumpeter Jimmy Deuchar, tenor saxophonists Ronnie Scott and Tommy Whittle, and drummer Phil Seaman were present. “Penitentiary Breakout” sounds like a small-group track at the outset, but eventually reveals itself as a big band piece. Hayes, Deuchar and Seaman all provide fine blues solos on this medium-tempo track. Constanzo’s bongo drums introduce the Latin-flavored “Chase and Capture”, which features all three tenors (Hayes taking the center spot). These two sessions, along with an amiable 1963 single release of “Sally” and “I Believe in You” are all collected on a single CD in the box set—the only disc here to include material from more than one album.

From the early 1930s through the late 1950s, a long-standing dispute between the UK and US musicians’ unions required American jazz musicians to perform in Britain as “variety acts”, which meant that they would only perform as soloists with UK ensembles. Mid-Fifties tours by the working groups of Gerry Mulligan and Dave Brubeck helped to thaw the international relationship, and in 1961—shortly after the release of “Tubbs”—British saxophonist Pete King negotiated a deal where Hayes would perform as a soloist at New York’s Half Note club for a month, while Zoot Sims played with the house rhythm section at Ronnie Scotts’ in London (Scott and King launched the famous London nightclub after the Jazz Couriers disbanded). For the American bookers and club owners who were still unaware of Hayes’ technical and artistic abilities, King simply played a few tracks from “Tubbs” and the hesitations disappeared.

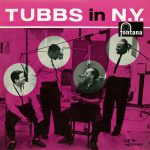

King also arranged for Hayes to record in New York with a to-be-selected  ensemble of American musicians. Several intriguing possibilities were floated, including trumpeter Donald Byrd, and the Miles Davis rhythm section, but eventually the group included trumpeter Clark Terry, vibraphonist Eddie Costa, pianist Horace Parlan, bassist George Duvivier, and drummer Dave Bailey. In the box notes, Spillett complains that the group had never recorded together before, but in truth, all of the musicians were working in a common musical language and had absolutely no problem melding together as a cohesive unit. The atmosphere in the studio was quite relaxed, with musicians, friends and journalists popping in and out, and the ad hoc group produced at least 74 minutes of music. The original LP’s, titled “Tubbs in N.Y” (UK) and “Tubby the Tenor” (US) each contained six tracks, but a 1990s US Columbia CD titled “The New York Sessions” included

ensemble of American musicians. Several intriguing possibilities were floated, including trumpeter Donald Byrd, and the Miles Davis rhythm section, but eventually the group included trumpeter Clark Terry, vibraphonist Eddie Costa, pianist Horace Parlan, bassist George Duvivier, and drummer Dave Bailey. In the box notes, Spillett complains that the group had never recorded together before, but in truth, all of the musicians were working in a common musical language and had absolutely no problem melding together as a cohesive unit. The atmosphere in the studio was quite relaxed, with musicians, friends and journalists popping in and out, and the ad hoc group produced at least 74 minutes of music. The original LP’s, titled “Tubbs in N.Y” (UK) and “Tubby the Tenor” (US) each contained six tracks, but a 1990s US Columbia CD titled “The New York Sessions” included  four additional tracks. Oddly enough, the Columbia CD was deleted from the catalog when Polygram (Fontana’s owner at the time) claimed ownership of the original album; however, Sony Music (Columbia’s current owner) apparently owns the four previously unissued tracks, which is the only logical explanation for why those tracks do not appear on the Universal box set. It is beyond my comprehension why little disputes like this cannot be resolved for the greater good of the music. There is at least one disc that has bootlegged the four extra tracks, but other than that, the only way to hear this music is to locate a copy of the Columbia CD (which sells for astronomical amounts on eBay and discogs). Hasn’t Universal Music figured out that the way to beat bootleggers is to issue superior versions on legitimate issues? This situation is particularly unfortunate considering the consistent excellence of the music. Hayes sounds eminently comfortable in these surroundings, creating one great solo after another, while realizing that his fellow musicians will maintain that high quality in their solos. This criticism is not meant to disparage the fine English musicians who worked with Hayes during the Sixties, but to note that American jazz musicians of the period were operating at a very high level, and it is a tribute to Hayes’ technical and musical prowess that he could still emerge as the star soloist amongst such elevated company. It should be noted that Hayes contemplated a permanent move to the US, but ultimately decided against it because he enjoyed his exalted position amongst British musicians, and that staying in the UK allowed him to teach new concepts to his fellow musicians.

four additional tracks. Oddly enough, the Columbia CD was deleted from the catalog when Polygram (Fontana’s owner at the time) claimed ownership of the original album; however, Sony Music (Columbia’s current owner) apparently owns the four previously unissued tracks, which is the only logical explanation for why those tracks do not appear on the Universal box set. It is beyond my comprehension why little disputes like this cannot be resolved for the greater good of the music. There is at least one disc that has bootlegged the four extra tracks, but other than that, the only way to hear this music is to locate a copy of the Columbia CD (which sells for astronomical amounts on eBay and discogs). Hasn’t Universal Music figured out that the way to beat bootleggers is to issue superior versions on legitimate issues? This situation is particularly unfortunate considering the consistent excellence of the music. Hayes sounds eminently comfortable in these surroundings, creating one great solo after another, while realizing that his fellow musicians will maintain that high quality in their solos. This criticism is not meant to disparage the fine English musicians who worked with Hayes during the Sixties, but to note that American jazz musicians of the period were operating at a very high level, and it is a tribute to Hayes’ technical and musical prowess that he could still emerge as the star soloist amongst such elevated company. It should be noted that Hayes contemplated a permanent move to the US, but ultimately decided against it because he enjoyed his exalted position amongst British musicians, and that staying in the UK allowed him to teach new concepts to his fellow musicians.

The new Tubby Hayes Quintet was premiered live in March 1962, and  recorded by Fontana over two nights in the following May. Two LPs were produced from these sessions, “Down in the Village” and “Late Spot at Scott’s”, and they display a top-notch group who had already mastered standards and bebop, and were ready to move into modal music. “Down in the Village” opens with a fiercely swinging arrangement of “Johnny One-Note” written by trumpeter Jimmy Deuchar. Hayes jumps in to the spotlight with a solo crammed full with notes, but also filled with stunning musical logic (How could he think and create at this burning tempo?) Deuchar was not the technician that Hayes was, but he does an admirable job of keeping pace with the flying rhythm section of Gordon Beck (piano), Freddy Logan (bass) and Allan Ganley (drums). Beck, playing on an out-of-tune instrument, doesn’t organize his ideas as well as Hayes or Deuchar, and his solo is quite short in comparison. A chamber version of “But Beautiful” with Hayes’ vibes accompanied only by bass and drums, includes a soulful middle chorus of improvisation that is an effective contrast with the crystalline sound of the opening chorus. Logan’s solo reveals his fine melodic sense, and Hayes brings out the multiple mallets again for the out-chorus. The full band returns for another Richard Rodgers show tune, “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World”. Following an opening fanfare by the horns alone, the band moves into a jazz waltz—still a novel concept at the time—but Hayes shows that 3/4 was no obstacle for him. Deuchar experiments with unusual phrase lengths in his solo, and Beck settles into the groove to create a fine improvisation. Ganley, one of England’s most musical drummers of the period, plays a series of elegant exchanges with the horns before launching into an extended solo. The title tune is a modal tune with a bridge in waltz time, inspired by the music Hayes heard in New York by the Miles Davis Sextet with Hank Mobley and J.J. Johnson. Hayes plays vibes on this track and his improvised phrases breathe with great clarity. Deuchar had grasped the concept of modal playing, although his brazen sound and flashy trills sound out of place here. Beck nails his solo, capturing the style and concept with aplomb. Hayes then picks up the soprano sax for an original modal waltz, “In the Night”. From a technical standpoint, Hayes gets around the straight horn very well, but his sound is pinched and nasal. It’s hardly a surprise that Hayes abandoned the soprano rather quickly, adopting the flute as his third instrument. The first album’s closer is a bop original by Deuchar, “First Eleven”. The composer takes the first solo, again varying phrase lengths while locking into the fast tempo. Hayes blasts through his tenor solo with volleys of notes, but Beck does the best job of organizing his ideas into intriguing phrases.

recorded by Fontana over two nights in the following May. Two LPs were produced from these sessions, “Down in the Village” and “Late Spot at Scott’s”, and they display a top-notch group who had already mastered standards and bebop, and were ready to move into modal music. “Down in the Village” opens with a fiercely swinging arrangement of “Johnny One-Note” written by trumpeter Jimmy Deuchar. Hayes jumps in to the spotlight with a solo crammed full with notes, but also filled with stunning musical logic (How could he think and create at this burning tempo?) Deuchar was not the technician that Hayes was, but he does an admirable job of keeping pace with the flying rhythm section of Gordon Beck (piano), Freddy Logan (bass) and Allan Ganley (drums). Beck, playing on an out-of-tune instrument, doesn’t organize his ideas as well as Hayes or Deuchar, and his solo is quite short in comparison. A chamber version of “But Beautiful” with Hayes’ vibes accompanied only by bass and drums, includes a soulful middle chorus of improvisation that is an effective contrast with the crystalline sound of the opening chorus. Logan’s solo reveals his fine melodic sense, and Hayes brings out the multiple mallets again for the out-chorus. The full band returns for another Richard Rodgers show tune, “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World”. Following an opening fanfare by the horns alone, the band moves into a jazz waltz—still a novel concept at the time—but Hayes shows that 3/4 was no obstacle for him. Deuchar experiments with unusual phrase lengths in his solo, and Beck settles into the groove to create a fine improvisation. Ganley, one of England’s most musical drummers of the period, plays a series of elegant exchanges with the horns before launching into an extended solo. The title tune is a modal tune with a bridge in waltz time, inspired by the music Hayes heard in New York by the Miles Davis Sextet with Hank Mobley and J.J. Johnson. Hayes plays vibes on this track and his improvised phrases breathe with great clarity. Deuchar had grasped the concept of modal playing, although his brazen sound and flashy trills sound out of place here. Beck nails his solo, capturing the style and concept with aplomb. Hayes then picks up the soprano sax for an original modal waltz, “In the Night”. From a technical standpoint, Hayes gets around the straight horn very well, but his sound is pinched and nasal. It’s hardly a surprise that Hayes abandoned the soprano rather quickly, adopting the flute as his third instrument. The first album’s closer is a bop original by Deuchar, “First Eleven”. The composer takes the first solo, again varying phrase lengths while locking into the fast tempo. Hayes blasts through his tenor solo with volleys of notes, but Beck does the best job of organizing his ideas into intriguing phrases.

In the liner notes to “Late Spot at Scott’s”, Terry Brown recalls that the  recording engineers worked in a tiny back room of the club and dealt with room temperatures of 90 degrees Fahrenheit. To my eyes, that is a recipe for equipment malfunctions, and the breakdown of a portable stereo tape recorder may well be the reason why “Late Spot” was only issued in mono (Box set producer Kevin Long told me that no stereo masters exist for this album). The sound has a little more distortion than “Down in the Village” and the music is less progressive, but the quintet still plays at top form. The album opens with Hayes’ “Half a Sawbuck”, a melodic bopper first recorded (and initially rejected) at Hayes’ New York sessions. The composer offers another stunning solo, with signature phrases set off against the running stream of notes. Deuchar uses space well in his choruses. Beck’s instrument sounds better here (did the piano tuner come by between the two nights of recording?) and the pianist appears to have relaxed in the interim. A short solo by Ganley brings back the attractive melody. The drummer provided a moody arrangement of “Angel Eyes” featuring melodic statements shared by Deuchar’s muted trumpet and Hayes’ vibes. The solos are quite short, and each musician creates a complete statement within their limited space. “The Sausage Scaper” is a funky soul-jazz piece, where Hayes develops his ideas well, and makes the most of the tune’s distinctive pedal point. Deuchar’s solo lacks direction, and there is a priceless moment when Ganley reacts to the sudden addition of a rasp in the trumpeter’s tone. Beck’s solo has an effortless groove and well-developed ideas. Hayes’ dramatic arrangement of George Gershwin’s “My Man’s Gone Now” breaks up the melody to bring out the anger implicit in the original aria. Hayes brings tremendous passion to his solo, Deuchar spits out forceful lines, and Beck offers momentary solace before the theme returns. The closing track is a spirited version of Horace Silver’s “Yeah!” with forcefully swinging solos by tenor, trumpet and piano, and outstanding ensemble work by the rhythm section.

recording engineers worked in a tiny back room of the club and dealt with room temperatures of 90 degrees Fahrenheit. To my eyes, that is a recipe for equipment malfunctions, and the breakdown of a portable stereo tape recorder may well be the reason why “Late Spot” was only issued in mono (Box set producer Kevin Long told me that no stereo masters exist for this album). The sound has a little more distortion than “Down in the Village” and the music is less progressive, but the quintet still plays at top form. The album opens with Hayes’ “Half a Sawbuck”, a melodic bopper first recorded (and initially rejected) at Hayes’ New York sessions. The composer offers another stunning solo, with signature phrases set off against the running stream of notes. Deuchar uses space well in his choruses. Beck’s instrument sounds better here (did the piano tuner come by between the two nights of recording?) and the pianist appears to have relaxed in the interim. A short solo by Ganley brings back the attractive melody. The drummer provided a moody arrangement of “Angel Eyes” featuring melodic statements shared by Deuchar’s muted trumpet and Hayes’ vibes. The solos are quite short, and each musician creates a complete statement within their limited space. “The Sausage Scaper” is a funky soul-jazz piece, where Hayes develops his ideas well, and makes the most of the tune’s distinctive pedal point. Deuchar’s solo lacks direction, and there is a priceless moment when Ganley reacts to the sudden addition of a rasp in the trumpeter’s tone. Beck’s solo has an effortless groove and well-developed ideas. Hayes’ dramatic arrangement of George Gershwin’s “My Man’s Gone Now” breaks up the melody to bring out the anger implicit in the original aria. Hayes brings tremendous passion to his solo, Deuchar spits out forceful lines, and Beck offers momentary solace before the theme returns. The closing track is a spirited version of Horace Silver’s “Yeah!” with forcefully swinging solos by tenor, trumpet and piano, and outstanding ensemble work by the rhythm section.

Soon after the Ronnie Scott’s gig ended, Hayes was on a plane back to America. This trip was not as well organized as the previous jaunt, and many details were not decided until the last minute. That was certainly the case with Hayes’ next recording, recorded in New York for the Mercury subsidiary  Smash, produced by Quincy Jones, and issued as “Return Visit” in the UK and as “Tubby’s Back in Town” in the US. Pianist Walter Bishop, Jr. was the only holdover from the trio Hayes worked with in the States, and the rest of the group was apparently hired just hours before the session. Three tenor players shared the front line (although each played doubles on the session): Hayes, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and James Moody—the latter appearing under the nom de disque of “Jimmy Gloomy”. The remainder of the rhythm section was the bass/drum team from Cannonball Adderley’s group, Sam Jones and Louis Hayes. The album never really catches fire: the bassist and drummer offer the only real musical chemistry; Tubby’s vibes lead and solo provide the sole interest in “Afternoon in Paris”; the expected tenor chase on Sonny Stitt’s “The Loose Walk” dissipates into a dull string of solos; and the main highlight of the ballad medley is Kirk’s reedless tenor solo on “For Heaven’s Sake”. Indeed, the only solo characteristic on this album to carry into Tubby’s later music was Kirk’s simultaneous singing and flute playing. Apparently, Tubby was trepidatious going into the session, and his limited inspiration failed to energize the rest of the group. Considering the talent involved, this album could have been much better, but instead, it just falls flat.

Smash, produced by Quincy Jones, and issued as “Return Visit” in the UK and as “Tubby’s Back in Town” in the US. Pianist Walter Bishop, Jr. was the only holdover from the trio Hayes worked with in the States, and the rest of the group was apparently hired just hours before the session. Three tenor players shared the front line (although each played doubles on the session): Hayes, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and James Moody—the latter appearing under the nom de disque of “Jimmy Gloomy”. The remainder of the rhythm section was the bass/drum team from Cannonball Adderley’s group, Sam Jones and Louis Hayes. The album never really catches fire: the bassist and drummer offer the only real musical chemistry; Tubby’s vibes lead and solo provide the sole interest in “Afternoon in Paris”; the expected tenor chase on Sonny Stitt’s “The Loose Walk” dissipates into a dull string of solos; and the main highlight of the ballad medley is Kirk’s reedless tenor solo on “For Heaven’s Sake”. Indeed, the only solo characteristic on this album to carry into Tubby’s later music was Kirk’s simultaneous singing and flute playing. Apparently, Tubby was trepidatious going into the session, and his limited inspiration failed to energize the rest of the group. Considering the talent involved, this album could have been much better, but instead, it just falls flat.

Aside from the single mentioned above, Hayes’ next two Fontana projects were big band albums. In the mid-1960s, large jazz ensembles were still viable artistic entities, even if the audiences were dwindling (the popular big bands led by Maynard Ferguson and Buddy Rich launched just after these Hayes recordings). Hayes loved writing for big bands and the ensembles he led were typically comprised of the best British jazz musicians working at the time. In recent years, there have been several newly discovered live recordings from this period of Hayes performing with his quintet, but during the mid-sixties, Hayes was typically heard in the media and recordings as a featured big band soloist. In addition to his own group, he recorded with orchestras led by Johnny Dankworth, Harry South, Georgie Fame, Kenny Clarke and Stan Tracey. In 1964, Hayes was asked to sub for the ailing Paul Gonsalves for a Duke Ellington Orchestra concert at Royal Festival Hall, and in the following year, he was a featured soloist in a big band backing Ella Fitzgerald.

“Tubbs’ Tours” was recorded in 1964 and was ostensibly a concept album,  featuring mostly original music celebrating the countries where Hayes had performed. As a musical travelogue, it is limited by some of the short-sighted attitudes of the time, but taken as a program of big band originals, it is very enjoyable with superb ensemble work and fine solos by the group. The opener, “Pedro’s Walk” was composed by Ian Hamer, and featured Hayes’ tenor, Terry Shannon’s piano, Logan’s bass and Ganley’s drums over a minor Spanish vamp. Hayes’ liner notes stated that this piece “always tears the place apart” at live gigs, an understandable appraisal considering the powerful brass riffs in the final chorus. Hayes’ “In the Night” returns, now presented as an elegantly swinging feature for the leader’s flute. Jimmy Deuchar’s “Russian Roulette” starts and ends with some obnoxious timpani pounding by the leader, but it soon becomes a fine minor swing piece with Deuchar and Shannon featured. “Raga” is an intriguing pastiche of Indian music, composed and arranged by Harry South, featuring layers of orchestration surrounding a Hayes flute solo which includes simultaneous singing and playing. Deuchar arranged Bud Powell’s “Parisian Throughfare” for the band, incorporating and expanding elements from the Clifford Brown/Max Roach recording, and leaving ample solo spots for his own mellophonium, Ronnie Ross’ alto and Hayes’ tenor. “The Killers of W.1” is the best track on the album, with four melodies appearing in sequence, swinging solos by Shannon, Hayes, Deuchar, Ross (baritone) and Ganley, and thrilling ensemble work by the band. The subtle ballad “Israel Nights” was co-composed by saxophonists Bobby Wellins and Jackie Sharpe, and it brings out some of Hayes’ most sensitive vibraphone playing. The original LP closed with Peter King’s “Sara-Hivi” which brings an exotic feel through an insistent 9/8 rhythm and a captivating Hayes tenor solo. The box set adds an unissued track, “Embers”, a Hayes ballad with a recurring rhythm section punctuation reminiscent of Neal Hefti’s “Li’l Darlin’”. The performance is quite lovely, but perhaps it was left unissued because it doesn’t seem to fit the album’s concept. It’s good to hear it at last. The Hayes Orchestra—with almost identical personnel to the album—played several of the pieces from “Tubbs’ Tours” on a 1965 episode of the acclaimed BBC-TV series “Jazz 625”. The complete show can be seen here.

featuring mostly original music celebrating the countries where Hayes had performed. As a musical travelogue, it is limited by some of the short-sighted attitudes of the time, but taken as a program of big band originals, it is very enjoyable with superb ensemble work and fine solos by the group. The opener, “Pedro’s Walk” was composed by Ian Hamer, and featured Hayes’ tenor, Terry Shannon’s piano, Logan’s bass and Ganley’s drums over a minor Spanish vamp. Hayes’ liner notes stated that this piece “always tears the place apart” at live gigs, an understandable appraisal considering the powerful brass riffs in the final chorus. Hayes’ “In the Night” returns, now presented as an elegantly swinging feature for the leader’s flute. Jimmy Deuchar’s “Russian Roulette” starts and ends with some obnoxious timpani pounding by the leader, but it soon becomes a fine minor swing piece with Deuchar and Shannon featured. “Raga” is an intriguing pastiche of Indian music, composed and arranged by Harry South, featuring layers of orchestration surrounding a Hayes flute solo which includes simultaneous singing and playing. Deuchar arranged Bud Powell’s “Parisian Throughfare” for the band, incorporating and expanding elements from the Clifford Brown/Max Roach recording, and leaving ample solo spots for his own mellophonium, Ronnie Ross’ alto and Hayes’ tenor. “The Killers of W.1” is the best track on the album, with four melodies appearing in sequence, swinging solos by Shannon, Hayes, Deuchar, Ross (baritone) and Ganley, and thrilling ensemble work by the band. The subtle ballad “Israel Nights” was co-composed by saxophonists Bobby Wellins and Jackie Sharpe, and it brings out some of Hayes’ most sensitive vibraphone playing. The original LP closed with Peter King’s “Sara-Hivi” which brings an exotic feel through an insistent 9/8 rhythm and a captivating Hayes tenor solo. The box set adds an unissued track, “Embers”, a Hayes ballad with a recurring rhythm section punctuation reminiscent of Neal Hefti’s “Li’l Darlin’”. The performance is quite lovely, but perhaps it was left unissued because it doesn’t seem to fit the album’s concept. It’s good to hear it at last. The Hayes Orchestra—with almost identical personnel to the album—played several of the pieces from “Tubbs’ Tours” on a 1965 episode of the acclaimed BBC-TV series “Jazz 625”. The complete show can be seen here.

For the 1966 album “100% Proof”, Universal has included a plethora of  unissued material. From the track list, it’s clear that the album was originally intended to feature big band versions of modern jazz standards. However, at the end of the final session, Hayes decided to try a single take of a self-penned saxophone feature originally written for a German radio broadcast. Not only was the 14-minute take deemed suitable for release, it became the title track of the album, and edged out three other previously accepted pieces. The track is a revelation, showcasing much of what Hayes had learned on tenor and predicting some of the directions his music would take in the next year. Near the beginning of the work, there is a stunning episode of free playing with the quartet, from which Hayes effortlessly segues into a sensuous slow blues with the big band. An up-tempo waltz follows, with Hayes providing more of the multi-noted runs that had stunned audiences and musicians for years. A cadenza (with touches of multiphonics) appears next, but instead of signaling the piece’s conclusion, it merely leads to another section, this one set at the burning tempo Hayes loved to play over. Another cadenza takes us back to the slow blues. A final cadenza (with elements of all of the earlier material) brings the piece to a close. Unlike many of the pieces from these sessions, there is no alternate take for “100% Proof”, but Universal has included a 1975 edit of the master, which was used for a Philips LP reissue.

unissued material. From the track list, it’s clear that the album was originally intended to feature big band versions of modern jazz standards. However, at the end of the final session, Hayes decided to try a single take of a self-penned saxophone feature originally written for a German radio broadcast. Not only was the 14-minute take deemed suitable for release, it became the title track of the album, and edged out three other previously accepted pieces. The track is a revelation, showcasing much of what Hayes had learned on tenor and predicting some of the directions his music would take in the next year. Near the beginning of the work, there is a stunning episode of free playing with the quartet, from which Hayes effortlessly segues into a sensuous slow blues with the big band. An up-tempo waltz follows, with Hayes providing more of the multi-noted runs that had stunned audiences and musicians for years. A cadenza (with touches of multiphonics) appears next, but instead of signaling the piece’s conclusion, it merely leads to another section, this one set at the burning tempo Hayes loved to play over. Another cadenza takes us back to the slow blues. A final cadenza (with elements of all of the earlier material) brings the piece to a close. Unlike many of the pieces from these sessions, there is no alternate take for “100% Proof”, but Universal has included a 1975 edit of the master, which was used for a Philips LP reissue.

Taking the rest of the “100% Proof” material in session order, there are two takes of Milt Jackson’s “Bluesology” which, in addition to being Hayes’ final recorded vibraphone solo, features well-scored sections for woodwinds, and powerful shout choruses. Hayes’ friend and co-leader of the Jazz Couriers, Ronnie Scott provides a fine tenor solo between vibes solos and brass exhortations. A single take of “Seven Steps to Heaven” includes exciting solos by Kenny Wheeler (trumpet), Hayes (tenor), Gordon Beck (piano), and Ronnie Stephenson (drums). Even though the band shouted its approval at the end of the take, the piece has remained unissued until now. Hayes and Scott lock tenors on a briskly-swinging take of “Sonnymoon for Two”. Hayes’ flute is spotlighted in Ian Hamer’s setting of “A Night in Tunisia”. Apart from a recasting of the melody, Hamer’s chart follows Dizzy Gillespie’s iconic big band arrangement. After Hayes’ impressive turn on flute, Hamer improvises on muted trumpet and engages in a powerful duet with Stephenson. There is a second take on the box set, along with an insert designed to replace problems with Hayes’ original cadenza.

Hayes’ arrangement of “Milestones” opens with an extended woodwind passage (perhaps an homage to Gil Evans’ introduction to Miles Davis’ Carnegie Hall version of “So What”?). Jeff Clyne’s unaccompanied bass leads to the main theme (with a fiendishly difficult countermelody for the woodwinds). Keith Christie’s trombone solo meanders between bop and scalar improvisation, Beck’s piano stays within the modal template, but (following another brutal chorus for the reeds) Hayes seems happy to simply play bebop licks over the modal background. It seems strange that the man who had taught modal improvising to his band just a few years earlier would abandon the idea at such an inopportune moment. Jimmy Deuchar’s fast-paced “What’s Blue?” survives in two full takes, and two tracks of inserts. The first full take breaks down at the end, and after some studio chatter, the band tries again with much better results. The coda still has problems, but a series of inserts failed to improve things, and the piece was eventually abandoned. The final day of recording started with two more tries on “Sonnymoon” (both rejected, but included in the box set). The version of “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most” which follows is a gem, and probably the most valuable unissued track of the box. Hayes plays with great warmth and delicacy, treating the melody with care, and adding the most tasteful embellishments. The support from the band and rhythm section is extraordinary, and when the arrangement moves into long-meter, Hayes maintains his focus on the song’s essence. Here at last was evidence that Hayes was a fully mature player, rather than a flashy technician. And yet, this lovely recording has languished in the vaults for over 50 years. I hope that it gets some well-deserved radio play now that it has finally been released. The last piece recorded (before the title track) was Stan Tracey’s functional arrangement of Thelonious Monk’s “Nutty”. Considering that “Nutty” had no solo spots for the leader, it’s hard to fathom why this track made it to the LP, and not “Spring”.

Neither “Tubbs’ Tours” nor “100% Proof” were imported to America, and while Hayes had made yearly trips to the US, no official recordings exist from those visits. Thus, the 1967 American jazz public had not heard a Tubby Hayes recording made after 1962, and had no idea about the changes that Hayes had brought to his music. The cadenzas and free sections of “100% Proof” gave some indications to British audiences, but even they must have been surprised at his next album, “Mexican Green”, a late masterpiece where Hayes played his most progressive music to date. His tone was now harder, and multiphonics became a regular element of his solo style. Cadenzas were longer and based on a single chord. He could (and frequently did) pull out his earlier bop and ballad styles, but the pervasive effect of John Coltrane and Joe Henderson could be heard in nearly every Hayes performance.

The album opens with “Dear Johnny B”, Hayes’ tribute to drummer Johnny Butts, who had worked with the saxophonist, and had died in a car accident in late 1966. It is a powerful, slashing up-tempo number, displaying the saxophonist’s anger rather than sorrow. Although there are enough elements to identify Hayes (the lightning-fast runs, the basic tone, swing), the intensity of his playing and the edgy style of the composition (with an insistent pedal motive) shows that Hayes was facing the new styles of jazz head-on. In this effort, he was abetted by a new young rhythm section, comprising Mike Pyne (piano), Ron Mathewson (bass) and Tony Levin (drums), who could propel Hayes in ways his previous bands could not. The title of the next track, “Off the Wagon”, referred to Hayes’ ongoing issues with substance abuse. After the theme statement, Hayes and the trio temporarily abandon the bouncy rhythm for a more open approach, only gradually letting the straight-ahead feel return in the second chorus. The pattern is repeated for Pyne’s solo, and both soloists gauge the development of their statements based on the activity of their fellow musicians. Matthewson starts his melodic solo a cappella, with light accompaniment from Pyne and Levin coming in later. The track closes with an impressive tenor cadenza. Pyne and the rhythm section play the entire melody of “Trenton Place” thus delaying the solo entrance of Hayes on flute. The piece depicts Hayes’ sighting of a family of deer after a late night visit to San Francisco, and Hayes appropriately offers a lyric solo without any vocal effects. “Second City Steamer” fulfilled the need for a Hayes feature played at a burning tempo. Although Hayes hints that the form and solo features were subject to change from performance to performance, this piece was the most straight-ahead on the album, and it frequently appeared on Hayes’ live gigs.

The album opens with “Dear Johnny B”, Hayes’ tribute to drummer Johnny Butts, who had worked with the saxophonist, and had died in a car accident in late 1966. It is a powerful, slashing up-tempo number, displaying the saxophonist’s anger rather than sorrow. Although there are enough elements to identify Hayes (the lightning-fast runs, the basic tone, swing), the intensity of his playing and the edgy style of the composition (with an insistent pedal motive) shows that Hayes was facing the new styles of jazz head-on. In this effort, he was abetted by a new young rhythm section, comprising Mike Pyne (piano), Ron Mathewson (bass) and Tony Levin (drums), who could propel Hayes in ways his previous bands could not. The title of the next track, “Off the Wagon”, referred to Hayes’ ongoing issues with substance abuse. After the theme statement, Hayes and the trio temporarily abandon the bouncy rhythm for a more open approach, only gradually letting the straight-ahead feel return in the second chorus. The pattern is repeated for Pyne’s solo, and both soloists gauge the development of their statements based on the activity of their fellow musicians. Matthewson starts his melodic solo a cappella, with light accompaniment from Pyne and Levin coming in later. The track closes with an impressive tenor cadenza. Pyne and the rhythm section play the entire melody of “Trenton Place” thus delaying the solo entrance of Hayes on flute. The piece depicts Hayes’ sighting of a family of deer after a late night visit to San Francisco, and Hayes appropriately offers a lyric solo without any vocal effects. “Second City Steamer” fulfilled the need for a Hayes feature played at a burning tempo. Although Hayes hints that the form and solo features were subject to change from performance to performance, this piece was the most straight-ahead on the album, and it frequently appeared on Hayes’ live gigs.

“Blues in Orbit” (not to be confused with the Duke Ellington’s album or composition) opens the second side with a brief excursion into the blues, featuring a theme with intriguing harmonic substitutions. “A Dedication to Joy” is a ballad dedicated to Hayes’ lover, Joy Marshall. Hayes displays the same rich tone he used on “Spring Can Really Hang You up the Most”, but in this case, the song is more volatile in its underpinnings. Levin tries to stir up emotions with his brushes, but for the most part, Hayes stays focused on his Getzian ballad style (This decision may have been an attempt to retain domestic tranquility; the original title of this tune was “When My Baby Gets Mad, Everybody Split!”). Hayes and the band have plenty of opportunities to let their emotions loose on the nearly-14-minute title track. Opening with a dramatic tenor flourish which leads to a stunning free episode and a powerful drum solo, the main theme is revealed in an up-tempo Latin groove. Other than the theme, the piece was a head arrangement, improvised over an agreed key center. After an up-tempo Pyne solo, Hayes’ declamatory cadenza brings back the multiphonics, but his ensuing solo starts very traditionally before moving into more modern territory. It is as if Hayes was trying to lead the audience through his evolution of his style from hard bop to free by gradually adding new style elements. Another Levin solo leads into an abstract Mathewson solo, which moves back and forth between arco and pizzicato lines, but is far removed from his solo style heard earlier on the album. Hayes responds with another angry outburst of notes and multiphonics, before Levin’s final solo leads back to the main theme. In the liner notes, Hayes writes that this piece didn’t always work out in live performances, but a live recording issued recently finds the quartet stretching out on the piece for nearly a half-hour and moving further afield than the original Fontana recording. In addition to the original LP, Universal has added an unissued sequence of two takes and a false start for “Dear Johnny B”, along with a fascinating alternate take of “A Dedication to Joy”.

Hayes was busted for drug possession on the same week that Fontana released “Mexican Green”. He spent large portions of 1967 and 1968 off the jazz scene owing to legal and health issues, and his next album “The Orchestra” was an effort to mend fences with Fontana, who was disappointed  with Hayes’ declining record sales. Hayes proposed a big band with strings album featuring pop tunes of the day (He also wanted to record his new quartet; that project will be mentioned below). Taken on its own terms, “The Orchestra” isn’t a bad record: some of the tunes are among the best pop songs written in the 1960s, the arrangements are fairly interesting—if rather dated, and the musicians play well. But it was all for naught, as the album failed to attract its target audience, and as a whole, it’s just not compelling enough to warrant any serious discussion. Thankfully, we have the outstanding “Grits, Beans and Greens” sessions to close out the set. This long-forgotten quartet project has renewed interest in Tubby Hayes, and presented the world with a remarkable addition to Hayes’ legacy. The box set includes the deluxe 2-CD version of the set in the same sound quality as the original set. You can read my review of this album here.

with Hayes’ declining record sales. Hayes proposed a big band with strings album featuring pop tunes of the day (He also wanted to record his new quartet; that project will be mentioned below). Taken on its own terms, “The Orchestra” isn’t a bad record: some of the tunes are among the best pop songs written in the 1960s, the arrangements are fairly interesting—if rather dated, and the musicians play well. But it was all for naught, as the album failed to attract its target audience, and as a whole, it’s just not compelling enough to warrant any serious discussion. Thankfully, we have the outstanding “Grits, Beans and Greens” sessions to close out the set. This long-forgotten quartet project has renewed interest in Tubby Hayes, and presented the world with a remarkable addition to Hayes’ legacy. The box set includes the deluxe 2-CD version of the set in the same sound quality as the original set. You can read my review of this album here.

I reviewed a digital download of this set, rather than the physical edition, so I can only make limited commentary regarding the packaging. I can say that the CD edition comes in a clamshell box (using the same generic cover art as “Grits, Beans and Greens”—why? There are plenty of great photos of Hayes that would have been suitable for cover art!). Each album is contained in a mini-LP sleeve (double sleeves for “100% Proof” and “Grits, Beans and Grits”). The LP version includes LP cover reproductions, but as noted above, no bonus tracks. The individual packaging of the albums should encourage Universal to issue the discs separately, and—most importantly—as imports. There are many American jazz fans who would benefit from hearing such treasures as “100% Proof” and “Mexican Green”, and there is no better time to issue those albums than now, while the buzz over “Grits, Beans and Greens” continues. Simon Spillett’s exhaustive liner notes (located in a miniature hardback book within the box) and the new second edition of his Hayes biography, “The Long Shadow of the Little Giant” are both treasure troves of information on Hayes, and both were of great value to me in writing this review. With most of his music now available commercially, it is a great time to check out the astounding music of Tubby Hayes. He was certainly one of the most extraordinary jazz musicians of the 20th century.