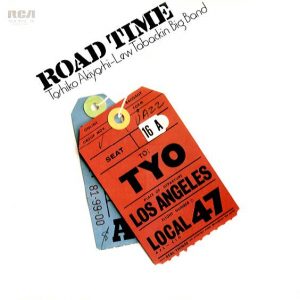

Toshiko Akiyoshi is not only one of jazz’s finest pianists, but also one of jazz’s  greatest living big band composers. It has also been said that she one of the most underrated musicians because she’s Japanese and a woman, but that has nothing to do with her exceptional talent and her valuable contributions to jazz. One of the things I love about her work is that it transcends song form and creates commanding musical landscapes that stand on their own and serve as springboards for the soloists. And of course there’s her powerhouse energy as both a writer and performer. “Road Time” is an out-of-print classic, although it can be found online with a bit of searching. This was her fourth album since forming her LA-based band in 1974, and it was the band’s first live recording, made at three concerts during a 1976 tour of Japan. The two-LP album received a 1977 Grammy nomination in the “Best Jazz Performance – Big Band” category.

greatest living big band composers. It has also been said that she one of the most underrated musicians because she’s Japanese and a woman, but that has nothing to do with her exceptional talent and her valuable contributions to jazz. One of the things I love about her work is that it transcends song form and creates commanding musical landscapes that stand on their own and serve as springboards for the soloists. And of course there’s her powerhouse energy as both a writer and performer. “Road Time” is an out-of-print classic, although it can be found online with a bit of searching. This was her fourth album since forming her LA-based band in 1974, and it was the band’s first live recording, made at three concerts during a 1976 tour of Japan. The two-LP album received a 1977 Grammy nomination in the “Best Jazz Performance – Big Band” category.

“Tuning Up” is a blues shuffle that is showcases the band’s soloists. After the band plays the sassy head, there’s a rousing tenor solo by Akiyoshi’s husband and musical partner Lew Tabackin, followed by some almost comical low bass trombone punctuations. This leads into a series of dynamic solos by various members of the band, including a feisty trumpet battle between Bobby Shew and Steven Huffstetter. “Warning: Success May Be Hazardous to Your Health” is a joyful medium tempo jazz-samba theme. It features Huffstetter’s trumpet and Gary Foster’s alto sax. Both are supported by Akiyoshi’s vigorous writing for the ensemble, before Peter Donald’s drum solo. The track also includes a brief sample of Akiyoshi’s trademark flute ensembles, which left me wanting more. The relentless, rabble-rousing swinger “Henpecked Old Man” is introduced by a masterful free-style solo by Tabackin on tenor that turns into a dialog with Shew. After Shew takes his own solo, Dick Spencer follows on alto sax. The piece takes up the entire B side of the first LP, and consists mainly of solos over bass/drum vamps and Akiyoshi’s punchy horn riffs, which gives structure to a loose jam piece.

The waltz “Soliloquy” opens with a stunning flute introduction by Tabackin and a brief melodic statement by Akiyoshi. There is a gorgeously harmonized minor line featuring the flutes which is followed by a passage by the full ensemble. Foster’s swinging alto enters with a solo spurred on by Akiyoshi’s piano and Gene Cherico’s gentle but driving bass. The solo is punctuated by trenchant intermittent phrases by the horns. Then Akiyoshi plays a rare piano solo that shows her sensitive command of the keyboard. After an electrifying section for the full band, Tabackin’s flute closes the piece with a heartfelt minor cadenza. “Kogun” was dedicated to a Japanese soldier discovered in the Philippine jungle who didn’t know that World War II had ended 30 years before. A startlingly original composition, “Kogun” just may be my favorite track, probably because of my own penchant for mixed musical cultures. Akiyoshi fuses jazz with Japanese traditional music, featuring an angular, yearning melody, a robust piano solo and an extended, complex a cappella flute solo by Tabackin. Kisaku Katada and Yutake Yazaki, playing traditional Japanese drums (one of them having pitch changes similar to an African talking drum) add a very special touch to this brilliant performance.

Akiyoshi’s composition “Since Perry” is dedicated to Japan’s turnaround since Commodore Perry’s US-Japan treaty of 1854. The piece starts out with a loose, free-style drum solo. The unison trombones lay down a foundation, and the full band bursts in, playing at a break-neck tempo until Tabackin steps in on tenor with a marathon solo that changes moods from frantic to sultry. Without a pause, he shifts into his original composition “Yet Another Tear”, which is a requiem for late tenor masters Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas and Paul Gonsalves. The album’s final track is “Road Time Shuffle”, written in honor of the Japanese tour. It is a happy, finger-snapping number punctuated by Akiyoshi’s superb ensemble sections and a marvelous flute interlude, closing with a joyous free-for-all.

When I interviewed Akiyoshi in 1985, after she and Tabackin had moved from Los Angeles to New York, she said in her usual self-effacing way: “. . . I’m not doing this to make a living out of it, even though it’s very fortunate that I am making a living. I’m not doing it for recognition, although it’s nice to get recognition. The bottom line is that I am doing this because I want to do it.” She paused and then added, “I think if you could put it in one word, it’s love. If you love something enough, you’ll put up with anything.”