Someone should write a script about the making of “The Real Ambassadors”. This true story has all of the great elements needed in a drama. In the mid-1950s, an idealistic young jazz composer (Dave Brubeck) angered by the unfair treatment of blacks in American society, collaborates with his wife (Iola Brubeck) on a satirical stage work that posits that the jazz musicians who tour the world for the US State Department bring more goodwill than the stuffy and square politicians usually put on the job. The young couple writes their play in the car while waiting for their children to complete their private music lessons. Iola writes lyrics to many of Dave’s instrumental works and devises the show’s book around the world’s most famous and beloved jazz musician (Louis Armstrong). As the script develops, a love story is added to contrast the political message. When the Brubecks decide that they simply must have Armstrong as the star of their production, they approach Armstrong’s agent (Joe Glaser) who says he is willing to let them talk to Armstrong, but behind the scenes, does all he can to thwart the operation. After numerous attempts to reach Armstrong, Dave finally connects with the great man outside his hotel room. The two artists talk and Armstrong agrees to do the show. Glaser is still unconvinced of the show’s merit and— more importantly—its financial viability. Several Broadway producers show interest, especially when Armstrong is listed as the star. An offer comes to stage the show in London, but the deal falls through. Dave convinces his record label (Columbia) to collect the show’s songs into an album, even though the show has not been staged. The all-star album is released with extensive liner notes but does not include a synopsis of the plot, leaving many listeners confused about the thematic connections between the songs. With hopes of their Broadway premiere fading, two old friends (Jimmy Lyons and Ralph J. Gleason) devise a plan to present a concert version of the show at the 5th Annual Monterey Jazz Festival. The musicians meet in San Francisco for a grueling rehearsal, and then on a cold September night, the cast (now including Iola as narrator, along with the Brubeck Trio, the Armstrong All-Stars, Carmen McRae, and Lambert, Hendricks, and Bavan) perform excerpts from the show for the festival audience. The audience reacts with an extended standing ovation, but Glaser has the last laugh as he deliberately refuses to let the performance be videotaped (despite a camera crew being on site to cover other events at the festival). Despite the warm reception from critics and audiences alike, the show is not revived or fully staged for another 40 years.

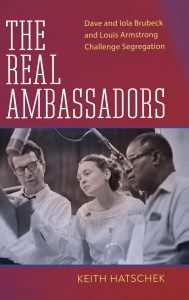

Celebrating the 60th anniversary of “The Real Ambassadors” Monterey performance, we now have the book which tells that story. Keith Hatschek’s “The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Segregation” (University Press of Mississippi) details the origins and development of the landmark production and offers a full discussion of the libretto and music. A comprehensive book like this has been needed for many years, and Hatschek’s narrative draws upon the previously published research of Penny Von Eschen, Ricky Riccardi, Philip Clark, and Stephen A. Crist. Working with the Brubeck family and the Armstrong archives, Hatschek spotlights little-known facts about the Brubecks (including a synopsis of two short stories written by Iola and published in 1947) and Armstrong (who had misplaced his “Ambassadors” music after the recording session and was frantically retyping lyrics and studying rehearsal tapes in preparation for the Monterey performance). Hatschek also details how Iola revised the script to reflect Armstrong’s triumphs on the State Department tours, including the hero’s welcome he received in an African country mired in civil war. Eugene Wright, Brubeck’s African-American bassist, also plays a key role in Hatschek’s saga as his presence in the otherwise-Caucasian quartet caused problems in the American South where mixed-race bands were prohibited by law. Brubeck lost approximately $40,000 in 1957 dollars on a single tour because he refused to replace Wright with a white bass player.

performance, we now have the book which tells that story. Keith Hatschek’s “The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge Segregation” (University Press of Mississippi) details the origins and development of the landmark production and offers a full discussion of the libretto and music. A comprehensive book like this has been needed for many years, and Hatschek’s narrative draws upon the previously published research of Penny Von Eschen, Ricky Riccardi, Philip Clark, and Stephen A. Crist. Working with the Brubeck family and the Armstrong archives, Hatschek spotlights little-known facts about the Brubecks (including a synopsis of two short stories written by Iola and published in 1947) and Armstrong (who had misplaced his “Ambassadors” music after the recording session and was frantically retyping lyrics and studying rehearsal tapes in preparation for the Monterey performance). Hatschek also details how Iola revised the script to reflect Armstrong’s triumphs on the State Department tours, including the hero’s welcome he received in an African country mired in civil war. Eugene Wright, Brubeck’s African-American bassist, also plays a key role in Hatschek’s saga as his presence in the otherwise-Caucasian quartet caused problems in the American South where mixed-race bands were prohibited by law. Brubeck lost approximately $40,000 in 1957 dollars on a single tour because he refused to replace Wright with a white bass player.

With 60 years of hindsight, it is fairly clear that the Brubeck “Real Ambassadors” was an uneven work. Iola’s lyrics have been called naïve on several occasions (including in Hatchek’s book), and Dave’s juxtaposition of pseudo-Gregorian chant with Armstrong’s heart-breaking song “They Say I Look Like God” forces a perspective that is already apparent and obvious. On the other hand, “Remember Who You Are” is a brilliant satire based on the debriefings given by State Department officials to jazz musicians embarking on an international tour. While most of the lyrics mimic the politician’s instructions to avoid discussions of civil rights, in a later song, Iola gives Armstrong a pivotal line: “Though I represent the government, the government don’t represent the things I stand for”. In essence, Armstrong’s fierce reaction to the Little Rock school segregation crisis, and his subsequent cancellation of a State Department-sponsored tour of the USSR, were the essential inspirations for “The Real Ambassadors”. The improbable love story between Armstrong and his band singer (McRae) was certainly the weakest part of the book, but it did yield two wonderful songs, McRae’s “My One Bad Habit is Falling in Love” (based on a quote from Ella Fitzgerald) and Armstrong’s emotional “Summer Song”, which stands as one of his greatest vocal recordings, regardless of era.

One element has been omitted from virtually every discussion of “The Real Ambassadors”, and that is the simple fact that Louis Armstrong, Carmen McRae, and the rest of the cast were not professional actors. While they could effectively communicate to audiences through music, that gift did not necessarily translate into carrying a Broadway show with dialogue, dramatic tension, and a substantial cast. Hatschek reports that Armstrong panicked at the task of memorizing dialogue for the Monterey performance until he was reassured that all of the lines would be on paper and he wouldn’t have to learn any new material beyond what he had recorded for Columbia a few months earlier. In retrospect, the concert version was the perfect way to present this work, with Iola delivering the basic story and the musicians concentrating on the songs. It is notable that most of the present-day revivals of “Real Ambassadors” revert to the concert format.

But what about that making-of movie? Wouldn’t that make a swell picture? Well, someone thinks so. In a press release from August 2022, producers Robert Lucchesi and Rick Gonzales have optioned the rights to Hatschek’s book for a feature film or a limited television series. There’s no guarantee that such a film will be made, but if it does happen, it will represent a rare instance of a jazz history book being translated into a film. In the meantime, we invite you to treat yourself to a wonderful 36-minute podcast by the Kitchen Sisters about the making of “The Real Ambassadors”.