One of the stated goals of all tribute albums is to enlighten listeners about a classic artist through the prism of a younger artist’s interpretation. Performing “their music our way” usually results in music that bears little resemblance to the original, but sound-alike performances are either redundant—as the original recordings can still be accessed—or artistically stagnant. Inevitably, elements of both approaches appear in any tribute album, but one approach comes with a detailed examination of the iconic artist’s compositions and repertoire. The four tribute albums reviewed below stand out for their selective approach to the playlist.

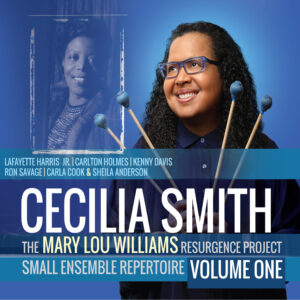

As the subject of three biographies, with nearly all of her music reissued during the CD era, and a long-running jazz festival named in her honor, I suspect that there are few serious jazz fans that are unfamiliar with the name and work of Mary Lou Williams. However, the name of vibraphonist Cecilia Smith‘s group, the Mary Lou Williams Resurgence Project implies that Smith wants to elevate Williams’ stature in jazz history. On her new album “Small Ensemble Repertoire, Volume 1” (Innova 89), she endeavors to connect her music with Williams’ through a mixture of new and old originals. The opening track, Smith’s “Sketch 1—Truth Be Told for MLW” operates in two tempos at once. The main melody, laden with quotes from bop tunes, shifts from its medium tempo every few bars. Meanwhile, drummer Ron Savage maintains an unchanging fast tempo on his cymbals. The two tempos are always distinct, even as the metric relationship between them changes. The near-blues “What Your Story, Morning Glory?” moves closer to Williams’ style, but the combination of Lafayette Harris, Jr.‘s piano with Carlton Holmes‘ B3 organ over Kenny Davis‘ bass creates a unique background for Smith’s straight-forward vibes and Carla Cook‘s soulful vocals. Smith’s intense and uncluttered solo style is displayed on the first of two versions of “Miss D.D.”. Over Savage’s deeply swinging brushes on snare, Smith effectively mixes multi-mallet technique with short, pithy improvised lines, making as much of a statement with silence as she does with sounds. Williams never recorded “Body & Soul” but she doubtlessly played it on gigs throughout her career. The version here is an elegant duet between Smith and Harris. Along with a later version of “St. Louis Blues”, this recording may be here to provide a suitable introduction to Smith for new listeners, using classic repertoire as the vehicles. “Sketch 3—100 Years of MLW” is a simple original melody over a light background that pairs gospel with a jazz waltz. “Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone” is a Williams secular piece that is shrouded in historical mystery. Williams never recorded it, and the lyric may have been written by Paula Stone, an actress and radio host from the 1940s (however, there is no definitive evidence connecting Williams and Stone). Cook’s vocal here reveals the song’s utter charm and soloists Smith and Harris have a lot of fun blowing over the changes. Another rare Williams composition, “Spiritual 2″—which only exists in fragmented form on Williams’ recordings and scores—is presented here as background to a spoken narration about Williams’ life read by WBGO host Sheila Anderson. Smith told me that she wanted the spoken elements on the recording for the benefit of those listeners that only access the album through digital downloads. This may not be the greatest solution to the lack of liner notes for online listeners, but we may have to deal with such tracks until the real thing comes along. The album concludes with live versions of “It’s a Grand Night for Swinging”, composed by Billy Taylor (who created the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival cited above) and “Miss D.D.” Smith’s blues choruses on the former show her commitment to the “less is more” strategy that was a key part of Williams’ training in Kansas City. Mary Lou would have been very proud of this living testament to her life and music.

of vibraphonist Cecilia Smith‘s group, the Mary Lou Williams Resurgence Project implies that Smith wants to elevate Williams’ stature in jazz history. On her new album “Small Ensemble Repertoire, Volume 1” (Innova 89), she endeavors to connect her music with Williams’ through a mixture of new and old originals. The opening track, Smith’s “Sketch 1—Truth Be Told for MLW” operates in two tempos at once. The main melody, laden with quotes from bop tunes, shifts from its medium tempo every few bars. Meanwhile, drummer Ron Savage maintains an unchanging fast tempo on his cymbals. The two tempos are always distinct, even as the metric relationship between them changes. The near-blues “What Your Story, Morning Glory?” moves closer to Williams’ style, but the combination of Lafayette Harris, Jr.‘s piano with Carlton Holmes‘ B3 organ over Kenny Davis‘ bass creates a unique background for Smith’s straight-forward vibes and Carla Cook‘s soulful vocals. Smith’s intense and uncluttered solo style is displayed on the first of two versions of “Miss D.D.”. Over Savage’s deeply swinging brushes on snare, Smith effectively mixes multi-mallet technique with short, pithy improvised lines, making as much of a statement with silence as she does with sounds. Williams never recorded “Body & Soul” but she doubtlessly played it on gigs throughout her career. The version here is an elegant duet between Smith and Harris. Along with a later version of “St. Louis Blues”, this recording may be here to provide a suitable introduction to Smith for new listeners, using classic repertoire as the vehicles. “Sketch 3—100 Years of MLW” is a simple original melody over a light background that pairs gospel with a jazz waltz. “Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone” is a Williams secular piece that is shrouded in historical mystery. Williams never recorded it, and the lyric may have been written by Paula Stone, an actress and radio host from the 1940s (however, there is no definitive evidence connecting Williams and Stone). Cook’s vocal here reveals the song’s utter charm and soloists Smith and Harris have a lot of fun blowing over the changes. Another rare Williams composition, “Spiritual 2″—which only exists in fragmented form on Williams’ recordings and scores—is presented here as background to a spoken narration about Williams’ life read by WBGO host Sheila Anderson. Smith told me that she wanted the spoken elements on the recording for the benefit of those listeners that only access the album through digital downloads. This may not be the greatest solution to the lack of liner notes for online listeners, but we may have to deal with such tracks until the real thing comes along. The album concludes with live versions of “It’s a Grand Night for Swinging”, composed by Billy Taylor (who created the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival cited above) and “Miss D.D.” Smith’s blues choruses on the former show her commitment to the “less is more” strategy that was a key part of Williams’ training in Kansas City. Mary Lou would have been very proud of this living testament to her life and music.

As the most obscure subject amongst these tribute albums, Dodo Marmarosa deserves an introduction. He was born in Pittsburgh in December 1925 and began intensive lessons in classical piano nine  years later. He became a jazz fan through a friendship with classmate Erroll Garner, and by 1944, he was working and recording in Los Angeles with Charlie Barnet‘s band. He rotated through the Tommy Dorsey and Artie Shaw orchestras, but his greatest renown occurred after he embraced the bebop style. He recorded with Charlie Parker on the “Night in Tunisia”/ “Ornithology” (March 1946) and “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” (February 1947) Dial sessions and under his own name for Atomic, Dial, and MacGregor transcriptions. He returned to Pittsburgh in 1950, and aside from occasional local gigs, and later albums for Argo and Prestige, he stopped playing. He is said to have received shock therapy during a stint in the Army, and that could well explain his lack of ambition during his later years. Marmarosa died in Pittsburgh in 2002. For his tribute to Marmarosa, a Pittsburgh pianist of the current generation, Craig Davis, joined forces with two current legends of LA jazz, bassist John Clayton and drummer Jeff Hamilton. The album, “Tone Paintings” (MCG Jazz 1056) is a collection of Marmarosa originals from his halcyon years in the City of Angels. “Mellow Mood”, the Marmosa recording most frequently anthologized in jazz piano collections, receives a sparkling arrangement here. Davis starts alone with an extended introduction and his guests enter in the most unexpected places. Davis retains some of Marmarosa’s voicings but balances them with his own clearly articulated style. “Dodo’s Bounce” is outfitted with a challenging harmonic progression. One part of the track’s charm is hearing Davis and Clayton twist their lines around the chords, while another part of the fun is Hamilton’s crisp and swinging brushwork. Clayton’s rich bass tones establish the deep groove of “Dodo’s Blues”. Even a spot of against-the-grain rhythm can’t disturb the mood, and Davis’ expressive solo builds upon all that came before to create an impressive climax. After the quick and intense “Escape”, Davis presents his sole original for the album, “A Ditty for Dodo”. The piece belies its title, as its smooth melody glides over a broken waltz feel. The Clayton-Hamilton partnership amazes again with its remarkable interaction. “Opus # 5” is reset over a light bossa rhythm, and Davis uses the sustain pedal to create a glimmering improvisation. The “Sweet Georgia” contrafact “Compadoo” brings out some of Davis’ most intense bop ideas, while “Dary Departs” features locked-hands style through the melody, contrasted with single lines in the ensuing solo. Marmarosa recorded “Tone Paintings I” as an unaccompanied piano improvisation without a clear harmonic progression. Davis, apparently playing from a written transcription of the original disc, wisely avoids the temptation to improvise on Marmarosa’s unique vision. “Battle of the Balcony Jive” comes from the Dorsey band’s appearance in an MGM movie called “Thrill of a Lifetime” (The piece was cut from the film and only exists on a rescued piece of soundtrack). The trio has a great time with the song here, and it’s strange that no one else has discovered the work, but as the CD jacket states, all of the Marmarosa pieces are now in the public domain. That problem needs to be rectified. MCG should arrange for the publication of Marmarosa’s music, so any remaining family members (or MCG jazz scholarship students) could benefit from the sales and royalties.

years later. He became a jazz fan through a friendship with classmate Erroll Garner, and by 1944, he was working and recording in Los Angeles with Charlie Barnet‘s band. He rotated through the Tommy Dorsey and Artie Shaw orchestras, but his greatest renown occurred after he embraced the bebop style. He recorded with Charlie Parker on the “Night in Tunisia”/ “Ornithology” (March 1946) and “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” (February 1947) Dial sessions and under his own name for Atomic, Dial, and MacGregor transcriptions. He returned to Pittsburgh in 1950, and aside from occasional local gigs, and later albums for Argo and Prestige, he stopped playing. He is said to have received shock therapy during a stint in the Army, and that could well explain his lack of ambition during his later years. Marmarosa died in Pittsburgh in 2002. For his tribute to Marmarosa, a Pittsburgh pianist of the current generation, Craig Davis, joined forces with two current legends of LA jazz, bassist John Clayton and drummer Jeff Hamilton. The album, “Tone Paintings” (MCG Jazz 1056) is a collection of Marmarosa originals from his halcyon years in the City of Angels. “Mellow Mood”, the Marmosa recording most frequently anthologized in jazz piano collections, receives a sparkling arrangement here. Davis starts alone with an extended introduction and his guests enter in the most unexpected places. Davis retains some of Marmarosa’s voicings but balances them with his own clearly articulated style. “Dodo’s Bounce” is outfitted with a challenging harmonic progression. One part of the track’s charm is hearing Davis and Clayton twist their lines around the chords, while another part of the fun is Hamilton’s crisp and swinging brushwork. Clayton’s rich bass tones establish the deep groove of “Dodo’s Blues”. Even a spot of against-the-grain rhythm can’t disturb the mood, and Davis’ expressive solo builds upon all that came before to create an impressive climax. After the quick and intense “Escape”, Davis presents his sole original for the album, “A Ditty for Dodo”. The piece belies its title, as its smooth melody glides over a broken waltz feel. The Clayton-Hamilton partnership amazes again with its remarkable interaction. “Opus # 5” is reset over a light bossa rhythm, and Davis uses the sustain pedal to create a glimmering improvisation. The “Sweet Georgia” contrafact “Compadoo” brings out some of Davis’ most intense bop ideas, while “Dary Departs” features locked-hands style through the melody, contrasted with single lines in the ensuing solo. Marmarosa recorded “Tone Paintings I” as an unaccompanied piano improvisation without a clear harmonic progression. Davis, apparently playing from a written transcription of the original disc, wisely avoids the temptation to improvise on Marmarosa’s unique vision. “Battle of the Balcony Jive” comes from the Dorsey band’s appearance in an MGM movie called “Thrill of a Lifetime” (The piece was cut from the film and only exists on a rescued piece of soundtrack). The trio has a great time with the song here, and it’s strange that no one else has discovered the work, but as the CD jacket states, all of the Marmarosa pieces are now in the public domain. That problem needs to be rectified. MCG should arrange for the publication of Marmarosa’s music, so any remaining family members (or MCG jazz scholarship students) could benefit from the sales and royalties.

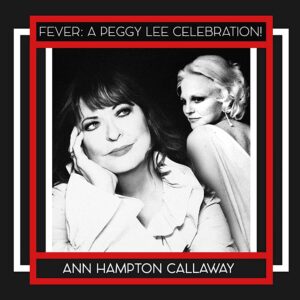

I’m always surprised when I find younger listeners who are unaware of Peggy Lee, by name or by her music. Lee was a best-selling recording artist for three decades and current reissues of her albums still excite a dedicated network of (older) collectors, but many others have apparently missed out on the subtle magic of this mesmerizing performer. Ann Hampton Callaway‘s new album, “Fever: A Peggy Lee Celebration” (Palmetto 2209) is based on a widely-acclaimed nightclub show that Callaway still performs. Callaway’s sexy purr through “Fever” starts as a close approximation of the original, but suddenly she adds an original chorus pulled from Lee’s personal life. “Till There Was You” makes the jump from Broadway to Rio with an added scat solo, and then John Pizzarelli joins in for a charming duet on “The Glory of Love”. On the next track, Peggy Lee’s spirit truly enters this disc. It is on the Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammerstein II standard, “The Folks Who Live on the Hill”. The intensity of Callaway’s performance, from her utter conviction in the homespun lyrics to the deep concentration on every phrase, builds on Lee’s original recording to create one of the most memorable ballad recordings in recent years. Callaway’s stellar quartet, with Ted Rosenthal (piano), Bob Mann (guitar), Martin Wind (bass), and Tim Horner (drums), provide great support throughout the album, but they are at their peak powers on this track. “Black Coffee”, the title track of one of Lee’s greatest albums, gets a splendid reading in Callaway’s hands. She makes the piece much more than just a torchy blues, effectively communicating the frustration of anyone who has endured a bad relationship. Callaway has thoroughly researched Lee’s life and work, and this album is enriched by several examples of Peggy Lee, the lyricist. Callaway set one unpublished poem to original music (“Claire de Lune”), and included a mix of her best-known songs (“I Don’t Know Enough About You”, “It’s a Good Day”, and “I Love Being Here with You”) with rarities like the selections from her autobiographical show, “Peg” (“The Other Part of Me” and “Angels on Your Pillow”). Her sensitive reading of the theme from “Johnny Guitar” has Callaway finding her own version of that slow-burning intensity that Lee could imply but would never state outright. Perhaps our younger listeners should check out Callaway’s album, and then investigate Lee’s considerable discography. They will be pleasantly surprised by the diversity between the original recordings and Callaway’s well-constructed remakes.

dedicated network of (older) collectors, but many others have apparently missed out on the subtle magic of this mesmerizing performer. Ann Hampton Callaway‘s new album, “Fever: A Peggy Lee Celebration” (Palmetto 2209) is based on a widely-acclaimed nightclub show that Callaway still performs. Callaway’s sexy purr through “Fever” starts as a close approximation of the original, but suddenly she adds an original chorus pulled from Lee’s personal life. “Till There Was You” makes the jump from Broadway to Rio with an added scat solo, and then John Pizzarelli joins in for a charming duet on “The Glory of Love”. On the next track, Peggy Lee’s spirit truly enters this disc. It is on the Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammerstein II standard, “The Folks Who Live on the Hill”. The intensity of Callaway’s performance, from her utter conviction in the homespun lyrics to the deep concentration on every phrase, builds on Lee’s original recording to create one of the most memorable ballad recordings in recent years. Callaway’s stellar quartet, with Ted Rosenthal (piano), Bob Mann (guitar), Martin Wind (bass), and Tim Horner (drums), provide great support throughout the album, but they are at their peak powers on this track. “Black Coffee”, the title track of one of Lee’s greatest albums, gets a splendid reading in Callaway’s hands. She makes the piece much more than just a torchy blues, effectively communicating the frustration of anyone who has endured a bad relationship. Callaway has thoroughly researched Lee’s life and work, and this album is enriched by several examples of Peggy Lee, the lyricist. Callaway set one unpublished poem to original music (“Claire de Lune”), and included a mix of her best-known songs (“I Don’t Know Enough About You”, “It’s a Good Day”, and “I Love Being Here with You”) with rarities like the selections from her autobiographical show, “Peg” (“The Other Part of Me” and “Angels on Your Pillow”). Her sensitive reading of the theme from “Johnny Guitar” has Callaway finding her own version of that slow-burning intensity that Lee could imply but would never state outright. Perhaps our younger listeners should check out Callaway’s album, and then investigate Lee’s considerable discography. They will be pleasantly surprised by the diversity between the original recordings and Callaway’s well-constructed remakes.

“Both Sides of Joni” (Acme 1) reverses the pattern of the above albums. In this case, the subject of the tribute—Joni Mitchell—is still alive and  able to enjoy and appreciate this music, but one of its primary creators, vocalist Janiece Jaffe passed away a few months before the release of this album. In collaboration with pianist/arranger Monika Herzig, Jaffe analyzed and reconsidered Mitchell’s songs to transform them into contemporary jazz. Greg Ward‘s unaccompanied alto saxophone begins the album as a lead-in to “Help Me”. Over a throbbing tango beat, Jaffe sings Mitchell’s lyrics with a few rough-edged tones and an occasional spoken phrase to emphasize the emotional depth of the words. Later in the track, she engages Ward in a loose exchange of improvised ideas. As the track builds to its final climax, the rhythm section of Herzig, Jeremy Allen (bass) and Cassius Goens (drums) raise thunder in support. Jaffe’s interpretation of “Both Sides Now” nearly turns it into a new tune, complete with fresh melodic inventions and a windswept jazz waltz background. On “I Think I Understand”, Jaffe overdubs her voice twice over to turn the lyric into a three-way conversation. Ward and Goens are in great form on this track as they inspire each other in a stunning dual improvisation. After a second vocal chorus, a new instrumental voice is added to the ensemble, that of violinist Carolyn Dutton who provides in turn, an obbligato, an improvised solo, and her own overdubbed background! In recent years, “River” has been adopted as a Christmas song, and the opening of Herzig’s arrangement has a Yuletide quality, but like the lyric, the mood changes when the holiday theme fades out. It soon becomes a powerful anthem of determination and regret. Herzig rides that mood in her solo before segueing back to the opening ideas. “Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow” was the initial inspiration for this project, and it has a raw, angry feel which continues to rumble and growl throughout the track. The carefree feel of “My Old Man” is a welcome contrast to the angst; in turn, Jaffe’s feathery scat solo at the end of that track contrasts with her wild free improvisation on “The Hissing of Summer Lawns”. “Sweet Bird” has a swaying background that alternates bars of five and six beats, and the closer “Circle Game” has a recurring music box motive to accentuate the lyric theme. In listening to this album, it is clear that the jazz world has lost a unique talent in Janeice Jaffe. For the album tour, Alexis Cole has bravely ventured to take Jaffe’s role. I have every confidence in Cole’s talents, and know that she has succeeded in this difficult task.

able to enjoy and appreciate this music, but one of its primary creators, vocalist Janiece Jaffe passed away a few months before the release of this album. In collaboration with pianist/arranger Monika Herzig, Jaffe analyzed and reconsidered Mitchell’s songs to transform them into contemporary jazz. Greg Ward‘s unaccompanied alto saxophone begins the album as a lead-in to “Help Me”. Over a throbbing tango beat, Jaffe sings Mitchell’s lyrics with a few rough-edged tones and an occasional spoken phrase to emphasize the emotional depth of the words. Later in the track, she engages Ward in a loose exchange of improvised ideas. As the track builds to its final climax, the rhythm section of Herzig, Jeremy Allen (bass) and Cassius Goens (drums) raise thunder in support. Jaffe’s interpretation of “Both Sides Now” nearly turns it into a new tune, complete with fresh melodic inventions and a windswept jazz waltz background. On “I Think I Understand”, Jaffe overdubs her voice twice over to turn the lyric into a three-way conversation. Ward and Goens are in great form on this track as they inspire each other in a stunning dual improvisation. After a second vocal chorus, a new instrumental voice is added to the ensemble, that of violinist Carolyn Dutton who provides in turn, an obbligato, an improvised solo, and her own overdubbed background! In recent years, “River” has been adopted as a Christmas song, and the opening of Herzig’s arrangement has a Yuletide quality, but like the lyric, the mood changes when the holiday theme fades out. It soon becomes a powerful anthem of determination and regret. Herzig rides that mood in her solo before segueing back to the opening ideas. “Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow” was the initial inspiration for this project, and it has a raw, angry feel which continues to rumble and growl throughout the track. The carefree feel of “My Old Man” is a welcome contrast to the angst; in turn, Jaffe’s feathery scat solo at the end of that track contrasts with her wild free improvisation on “The Hissing of Summer Lawns”. “Sweet Bird” has a swaying background that alternates bars of five and six beats, and the closer “Circle Game” has a recurring music box motive to accentuate the lyric theme. In listening to this album, it is clear that the jazz world has lost a unique talent in Janeice Jaffe. For the album tour, Alexis Cole has bravely ventured to take Jaffe’s role. I have every confidence in Cole’s talents, and know that she has succeeded in this difficult task.