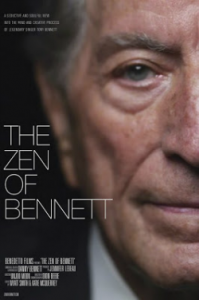

Tony Bennett is one of the primary icons of American music. His biography has been told through myriad articles, books, liner notes, and documentaries. The latest entry is a DVD called “The Zen of Bennett” (there is also a Bennett-penned book with a similar title). The film is an advanced seminar on the vocalist, as it assumes that the viewers already know Bennett’s life story and can thus appreciate the philosophy that makes him a great artist. Produced by Bennett’s son, Danny and directed by Unjoo Moon, the film uses Bennett’s album “Duets II” as a framework, observing the vocalist as he works with a variety of other singers, including Michael Bublé, Aretha Franklin, Willie Nelson and Amy Winehouse.

Tony Bennett is one of the primary icons of American music. His biography has been told through myriad articles, books, liner notes, and documentaries. The latest entry is a DVD called “The Zen of Bennett” (there is also a Bennett-penned book with a similar title). The film is an advanced seminar on the vocalist, as it assumes that the viewers already know Bennett’s life story and can thus appreciate the philosophy that makes him a great artist. Produced by Bennett’s son, Danny and directed by Unjoo Moon, the film uses Bennett’s album “Duets II” as a framework, observing the vocalist as he works with a variety of other singers, including Michael Bublé, Aretha Franklin, Willie Nelson and Amy Winehouse.

Bennett emerges as a consummate show business professional who is quite stubborn in adherence to his own beliefs. When Bennett first signed with Columbia Records in 1950, he was assigned to work with their pop A&R man, Mitch Miller. Miller went for the lowest common denominator in pop music, and Bennett fought contentiously to record better music. Bennett didn’t win all of those arguments, and that has made him very sensitive about the quality of his current recordings. During a rehearsal of “The Way You Look Tonight”, Bennett’s musical director, Lee Musiker, opines that the demo recording was played too slow, and offers a faster tempo. Bennett vetoes the idea immediately, insisting that they use the arrangement that they play in concerts. In a telling statement, Bennett says he wants to make a definitive recording of the song, and when they play the song as Bennett requested, it’s clear that he was absolutely correct in his convictions.

Bennett remembers that in his generation, the older pop stars weren’t very generous to upcoming singers, and he has vowed to make it easier for younger performers today. As he and Winehouse start to rehearse their duet version of “Body and Soul”, Winehouse is extremely nervous, not only because she’s recording with Bennett, but also because she hasn’t been in a recording studio for awhile. She takes daring chances in note choices and phrasing, but she recognizes that they’re not right and is about ready to give up. Bennett calms her down, praises her for what she’s tried, and tells her that they have plenty of time to get it right. After a few more attempts, Bennett relates a story about Dinah Washington, who he correctly assumed was one of Winehouse’s influences. She loosens up instantly, regains her focus, and they record the master take. It would be Winehouse’s final recording, and one wonders if she would have lived longer and happier had her encounter with Bennett occurred a few years earlier.

While it runs less than 90 minutes, “The Zen of Bennett” expects a great deal of patience from its audience. There are several sections that slow the film down to a crawl, including an exasperating sequence where Bennett talks with Danny about a joint interview for People magazine with John Mayer. Bennett seems to think that the piece will highlight the differences between the old and young generations (which he opposes), and Danny tries to reassure him that the “Duets II” project breaks down those differences. Essentially, the two men are on the same side of the issue, but we have to watch five minutes of arguing before they understand that. At times, the film seems to take itself too seriously, with long static shots of Bennett’s eyes over a superimposed screen of clouds. But in another sequence, they seem to parody that self-importance: Bennett and his sidemen are shown for nearly a minute sitting motionless and silent in a dressing room. Finally, Bennett’s daughter Antonia breaks the tension (and the pose) by asking when the show is supposed to start.

“The Zen of Bennett” was produced for Netflix, and the documentary can be rented through them. Sony Music has also released a DVD version, which includes bonus footage, deleted scenes and interviews with the filmmakers.