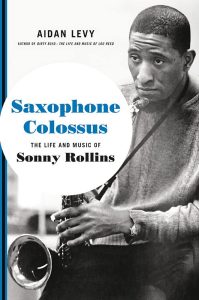

Sonny Rollins is rightly considered “the world’s greatest living jazz improviser” even though he has been unable to play his tenor saxophone for several years. In the last decade of his performing career, he was held in the highest esteem by his fellow musicians, and he commanded premium fees for concert appearances. His albums (some dating back 70 years) still sell, and his solos are studied by jazz musicians all over the globe. Yet for all this acclaim, very little has been published about Rollins’ personal life. We knew that he was born in New York to West Indian parents, that his earliest recordings were with Babs Gonzales, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis, that he kicked a drug habit and stayed straight due to the influence of Clifford Brown, that he unintentionally created the first recordings of thematic improvisation, that he pushed himself to the edge of the avant-garde before retreating on a sabbatical, during which time he practiced on the Williamsburg bridge, that he emerged from that period as a fierce improviser, that he visited India on another sabbatical, and that he embraced fusion in his  final decades. From these few lines of cryptic biography, Aidan Levy has written a 700+ page book “Saxophone Colossus” (Hachette) which fills in many essential details about Rollins’ life and career.

final decades. From these few lines of cryptic biography, Aidan Levy has written a 700+ page book “Saxophone Colossus” (Hachette) which fills in many essential details about Rollins’ life and career.

The first half of the book is the most enlightening. Covering Rollins’ birth (and his family tree) through his first sabbatical, Levy’s text is loaded with fascinating details. The young Rollins learned the basics of saxophone at the New York School of Music but learned about jazz on his own through recordings and live concerts. His regime of long practice sessions began when he was a boy, and he would play inside a closet to avoid disturbing the neighbors. He led a band in high school with Jackie McLean and Art Taylor as fellow members, and he studied with Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell before making his first records in 1949. He picked up his drug habit soon after graduation from high school and served time at Rikers Island in New York. He met pianist Elmo Hope while incarcerated, and their collaborative tune “Carvin’ the Rock” was premiered on Clifford Brown’s first recording session as a leader. Rollins was a visitor at the session, but ironically, he did not speak to Brown. During the 2 ½ years before their paths crossed again, Rollins would serve another short sentence at Rikers and then move to Chicago to restart his life and career. He was homeless for portions of his stay, but he eventually landed at the YMCA, where he practiced with a 17-year-old trumpeter from Memphis named Booker Little. Finally, in November 1955, Rollins was invited to join the Clifford Brown-Max Roach Quintet while the band was in residency at the Bee Hive, a popular South Side jazz club.

Virtually all of the historical information in the previous paragraph is a result of Levy’s groundbreaking research. Pieces of new information can be found on nearly every page of this book, and there is a genuine sense of awe at the sheer number of great musicians who crossed paths with Rollins. Levy balances this material with incisive critiques of Rollins’ many recordings, and he also offers as much information as he can regarding live performances (even those that were not taped). Rollins’ wife (and later manager) Lucille gets significant credit for building up the saxophonist’s later career, and by the time Levy tells of her death, he has shown numerous examples of how Lucille’s contributions made a difference, and why Sonny was so devastated by her passing.

Throughout his career, Rollins has been notoriously self-critical. Performances and recordings which left musicians, critics and audiences slack-jawed have been written off by the artist as “not my best work” or “a night when I didn’t play very well”. Levy claims that Rollins was looking for “the lost chord” (a trite reference that gets worn out with Levy’s overuse). To the end goal of finding musical perfection, Rollins had a revolving door of sidemen who were hired, fired, and re-hired at an alarming rate. An album of alternate takes from Rollins’ period at RCA Victor was issued without his permission, and Sonny and Lucille sued for the recordings to be removed from circulation. Lucille was especially hard on those fans who recorded Sonny’s concerts without permission (and permission was almost always denied). It was not until after Lucille’s death that Sonny agreed to evaluate—and eventually issue portions of—a library of unauthorized concert recordings owned by collector Carl Smith. All of these activities were supposedly connected with Rollins’ search for the lost chord. But what was Rollins searching for? Certainly, he realized that an improvised art had little chance of absolute perfection, but was always capable of creating enlightening moments. Did anyone ever ask Rollins what he sought? Did the question not come up among the many hours of interviews that Levy held with Rollins?

Considering in equal portions, the academic research, the openness of the subject, the tremendous amount of detail, and the wide variety of interviews, can we call “Saxophone Colossus” a definitive biography? To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. However, I can say with certainty that we are unlikely to find any jazz biography with as much new information as this one. Levy’s book is not always an easy read, and due to its massive size, it requires a significant time commitment just to read it from cover to cover. Overall, the book has tremendous historical value, and I am glad that I will have it as a reference whenever I pull my Rollins discs off the shelf, or when I wish to remind myself of Rollins’ stature as a great artist.