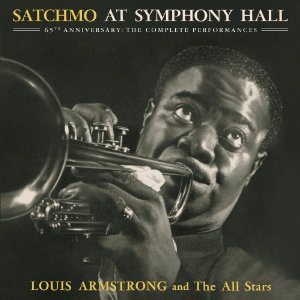

1947 was a seminal year for Louis Armstrong. In December 1946, several swing orchestras (including those of Benny Goodman and Woody Herman) had disbanded, but Armstrong still had his big band, and they continued to tour despite increasing economic difficulties and changing popular tastes. Enter Ernie Anderson, an Armstrong fan and concert promoter who offered Joe Glaser a tidy sum of $1000 to present the trumpeter in a small group concert at New York’s Town Hall in May. That concert was such a success that the big band was dissolved a few weeks later, the All-Stars (as the group came to be called) recorded a few sides for Victor, and Armstrong accepted a small group engagement at Billy Berg’s club in Hollywood that August. By the time the All-Stars returned east for Anderson-sponsored concerts at Carnegie Hall and Boston’s Symphony Hall, they had solidified both the personnel and repertoire of the group. Anderson had the good sense to record his concerts: the Carnegie performances are still unreleased, but the Town Hall concert was issued in part by Victor (and complete only by the French branch of the company), and most of the Symphony Hall performance was issued by Decca. For its 65th anniversary, Universal has issued a complete version of “Satchmo at Symphony Hall” including about 30 minutes of music unheard since the original concert.

1947 was a seminal year for Louis Armstrong. In December 1946, several swing orchestras (including those of Benny Goodman and Woody Herman) had disbanded, but Armstrong still had his big band, and they continued to tour despite increasing economic difficulties and changing popular tastes. Enter Ernie Anderson, an Armstrong fan and concert promoter who offered Joe Glaser a tidy sum of $1000 to present the trumpeter in a small group concert at New York’s Town Hall in May. That concert was such a success that the big band was dissolved a few weeks later, the All-Stars (as the group came to be called) recorded a few sides for Victor, and Armstrong accepted a small group engagement at Billy Berg’s club in Hollywood that August. By the time the All-Stars returned east for Anderson-sponsored concerts at Carnegie Hall and Boston’s Symphony Hall, they had solidified both the personnel and repertoire of the group. Anderson had the good sense to record his concerts: the Carnegie performances are still unreleased, but the Town Hall concert was issued in part by Victor (and complete only by the French branch of the company), and most of the Symphony Hall performance was issued by Decca. For its 65th anniversary, Universal has issued a complete version of “Satchmo at Symphony Hall” including about 30 minutes of music unheard since the original concert.

The Town Hall concert had featured Armstrong with a hand-picked group, including cornetist Bobby Hackett, trombonist Jack Teagarden, clarinetist Peanuts Hucko, pianist Dick Cary, bassist Bob Haggart, and drummer Sid Catlett (with George Wettling sitting in during the latter part of the concert). By the time of the Hollywood engagement, Hackett was out, Haggart was replaced by Morty Corb, and Hucko was replaced by Ellington alumnus Barney Bigard. Bigard may have been the key to Armstrong’s change-up of repertoire. The music for Town Hall was a retrospective of Armstrong’s greatest hits, but with Teagarden, Catlett and Bigard onboard, Armstrong could diversify his program to feature each of these star musicians instead of repeating his old triumphs. There was still room for “Muskrat Ramble”, “Back O’Town Blues” and “High Society”, but “Big Butter and Egg Man”, “Sweethearts on Parade” and “Save It Pretty Mama” could be retired. Over the next few months, Corb would be replaced by Arvell Shaw and Velma Middleton would become Armstrong’s vocalist and comic foil. In the evolving All-Star repertoire, Shaw and Middleton also had feature spots.

Teagarden was one of Armstrong’s greatest duet partners. He had been featured on the Town Hall concert, but at Symphony Hall, his features are longer and better developed. The Boston version of “St. James’ Infirmary” seems darker than the Town Hall recording, especially at the end when he plays some menacing growls on his bucket-muted trombone. While it’s surprising that Armstrong and Teagarden didn’t reprise their famous “Rockin’ Chair” duet in Boston, there’s a glorious version of “Stars Fell on Alabama” with a free and relaxed Teagarden vocal backed with tender Armstrong counterpoint. There’s also a previously unreleased “Jack-Armstrong Blues” with much more interplay between the two principals than on the Town Hall version. It is a testament to Armstrong’s regard for Teagarden that the closing theme for each set is “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues”. Both men had hit versions of Harold Arlen’s song, with Teagarden’s version recorded first.

Bigard is also in great form, with a delightful “Tea For Two” that includes Bigard’s and Catlett’s version of the Benny Goodman/Gene Krupa “Sing, Sing, Sing” duet, a beautifully-paced version of “Body and Soul” and a “C Jam Blues” featuring a duet between Bigard and Shaw. Middleton’s solo features are less successful than her hilarious duet with Armstrong on “That’s My Desire” (here in its first recording). Catlett was not big on drum solos, but he has several great spots on the Symphony Hall set, including a powerful outing on “Mop Mop” and on the band’s original “Steak Face”. Catlett also accentuated some of Middleton’s dance moves, and on “Velma’s Blues” (also newly restored) he provides us clues about the dance moves we can’t see. Armstrong is great form throughout the concert, with an emotional version of “Black and Blue”, a rocking “Mahogany Hall Stomp” capped by a brilliant sustained high B-flat, and an ever-building set of blues choruses on “Jack-Armstrong”.

The new edition of the Symphony Hall concert is outfitted in a hardback package with detailed notes on the restored deletions, and the corrections made to the tune list. In his reissue notes, Ricky Riccardi tells of the history of the recording, and how private copies of the acetates held by a Swedish collector helped to bring the Symphony Hall recording to its complete state. What Riccardi doesn’t mention is the widely varying quality of the sound. There is a disclaimer that says the sound varies according to the source material, but that doesn’t explain how the sound for previously issued material suddenly changes from open and warm to pinched and constricted—sometimes in the same track! With all of today’s digital technology, it’s a shame that the sounds from various sources can’t be made consistent. Every time the sound shifts in quality, our attention focuses on the audio instead of the music, which is where we should stay focused. And this music deserves our attention. It’s marked as a limited edition, so grab a copy while you can!