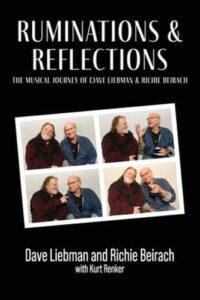

In the opening jacket blurb for “Ruminations and Reflections” (Cymbal Press), Pat Metheny writes, We really don’t have an exact name for musicians like Dave and Richie. Across decades of recordings and concerts, their aspirations obliterate the definitions of any single genre…. Both are master players who continue to strive for what goes beyond and what lies beneath. Despite an abundant discography, star-studded resumés, and overwhelming acclaim from their peers, saxophonist Dave Liebman and pianist Richie Beirach are barely mentioned in major jazz history books. While those books can only discuss a limited number of iconic musicians, the story of the Liebman/Beirach partnership deserves to be heard. “Ruminations and Reflections” draws from several conversations between the two musicians, which trace their remarkable 50+ years of collective music-making.

several conversations between the two musicians, which trace their remarkable 50+ years of collective music-making.

The book opens with the first meeting of Liebman and Beirach, at a 1967 jam session at Queens College in New York. In hindsight, Beirach admits that he only knew “a tune and a half” at that time and that Liebman had far more experience as a jazz musician. After the session, Liebman and Beirach went out to the parking lot, and on the hood of Liebman’s Chevy Bel Air, the saxophonist instructed the pianist on what tunes to learn. By early 1969, each had found apartments in lower Manhattan about a mile and a half away from each other. Liebman had a loft where he held free open jam sessions, and Beirach was a frequent visitor. The two spent much of their time transcribing records and rehearsing as a duo. Liebman was also responsible for finding two new tenants for the building. To explain how Dave Holland and Chick Corea became his new neighbors, Liebman takes a sudden backward leap to the months before he met Beirach to a pivotal trip he made to London, where—on his first night in town–he met Holland and several other jazz lions at Ronnie Scotts’ club. At Holland’s invitation, Liebman moved in to the bassist’s flat for three weeks; when Holland moved to New York as a member of Miles Davis‘ band, Liebman returned the favor by recommending Holland to his landlord. Soon after that, Corea was in search of an apartment after getting a divorce, and once again, Liebman came to the rescue.

Liebman’s time-jump is a little jarring (especially three pages into the book!) but narrative inconsistencies are a recurring problem with this memoir. There are numerous stories told about musicians and hangers-on, and it is fairly easy to surmise that many of them are apocryphal. Perhaps the most egregious example concerns the bebop pianist Al Haig. While discussing a long-closed restaurant that featured live jazz, Beirach makes a passing reference that Haig played there while on bail after killing his wife. In truth, Haig was acquitted of murder in that 1968 case, and the only person who ever questioned that verdict was Haig’s previous ex-wife, who discussed her theory of the murder in a book published nearly 40 years after the event, and 15 years after Haig’s death! Someone needed to fact-check the interview transcripts before the Liebman/Beirach memoir was published…and it wouldn’t hurt to do so before publishing another edition.

After a thorough and entertaining discussion of their lives in the 1970s, Liebman and Beirach offer their opinions of several famous musicians and other music-related topics. The discussion of jazz education is especially enlightening, with in-depth examples of the new ways in which young jazz musicians learn their craft. With touring big bands and major record companies a thing of the past, and many of the older giants unable to support apprentice musicians, music students can only get the training they need through master classes, YouTube videos, and participation in established university ensembles. Liebman admits that the level of teaching jazz at the college level has improved significantly in the last few years. Both men eventually agree that the real-world experiences of playing on the road are essential to being a fully-professional jazz musician. Their other opinions are less considered. Their appraisals of Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner, and Herbie Hancock are based on single albums rather than career overviews, and Beirach seems overly harsh on Corea, citing a perceived drop in creativity (starting with “Light as a Feather“), and blaming it on Corea’s belief in Scientology. Beirach is entitled to his own opinion, but it seems reckless to write off 50 years of music that has been widely acclaimed elsewhere.

The book improves as it continues with a tour of Brooklyn and Manhattan, with the two men reminiscing about their early years (Ironically, they grew up within blocks of each other in Brooklyn, but never met until that jam session in 1967). The warm feelings continue with a series of letters that Liebman and Beirach wrote to their deceased jazz heroes. Liebman shows deep appreciation for the lessons he learned from Miles Davis, Pete La Roca, and Elvin Jones, while Beirach reveals his admiration for Chet Baker and Stan Getz (while questioning the latter about his abrupt changes of attitude). There is a superb transcription of a jazz appreciation lecture delivered to a group of Polish non-musicians, followed by a detailed explanation of the duo’s preparation for concerts and recordings. The final section is perhaps the most interesting, as Beirach self-critiques 22 of the duo’s albums. Some of the essays concentrate on the circumstances of the recording sessions, but the best comments come when he talks about the music itself (especially when discussing different recordings of the same composition by Liebman and Beirach’s collectively led quartet, Quest).

“Ruminations and Reflections” is not the book it might have been, but unlike the biographies of the past, this memoir is apparently published on demand. This makes revisions and corrections almost as easy as revising the text on a website. With a thorough fact-check, general copy-editing, and some re-writing, future editions of this book would be a worthy testament to the collective genius of its subjects.