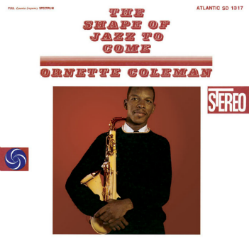

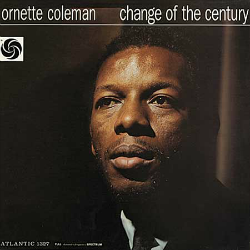

I’ll never forget the first time I heard these two albums. It was in 1960, and I was hanging out with my avant-garde jazz musician pals in Boston. When we first listened to Ornette Coleman’s brazenly titled “The Shape of Jazz to Come” and “Change of the Century,” we couldn’t stop talking about them. We’d never heard any music quite like this before. We’d been playing at jam sessions with Sam Rivers, but this wasn’t that kind of avant-garde—it wasn’t “out,” in the strict sense of the word. It had melody and changes and improvisation, but there was something about it that was brand new and completely original. We were, to put it simply, blown away.

I’ll never forget the first time I heard these two albums. It was in 1960, and I was hanging out with my avant-garde jazz musician pals in Boston. When we first listened to Ornette Coleman’s brazenly titled “The Shape of Jazz to Come” and “Change of the Century,” we couldn’t stop talking about them. We’d never heard any music quite like this before. We’d been playing at jam sessions with Sam Rivers, but this wasn’t that kind of avant-garde—it wasn’t “out,” in the strict sense of the word. It had melody and changes and improvisation, but there was something about it that was brand new and completely original. We were, to put it simply, blown away.

When I interviewed Coleman in 1986, he had this to say about improvisation: I now call it free-phrasing, but when I used to try to improvise I thought it was just that—something you had never done before. I never thought about it as something you were trying to interpret, like if you have a hat on and you put a feather in it and suddenly it looks different. You can improvise and make a person think you have a hat on. Although Coleman has varied and expanded his own “hats” over the years to include a double quartet and works for symphony orchestra, nothing is quite as captivating as the disarming simplicity and compelling fire of his work on these two albums. From the yearning mournfulness of “Lonely Woman” to the sassy jive of “Ramblin’,” Coleman, along with Don Cherry on pocket trumpet and cornet, Charlie Haden on bass and Billy Higgins on drums, gives new meaning to the word “free,” showing that sometimes the greatest sense of freedom rests on structure, however malleable and protean that structure may be.

Coleman met Cherry in 1956 and immediately sensed a strong musical affinity. Then Haden appeared and changed the role of bassist from accompanist to active participant in the music, as an equal voice, a style that later on characterized a number of jazz groups, notably the Bill Evans trios. Higgins proved to be the perfect foil for the group, always flexible, deftly handling tempo changes without ever losing his sense of swing. And what about that plastic sax? Coleman said that when he bought his first plastic alto, it was because he needed a new instrument, but couldn’t afford a brass one. He said, After living with the plastic horn, I felt it begin to take on my emotion. The tone is breathier than the brass instrument, but I came to like the sound, and I found the flow of music to be more compact. I don’t intend ever to buy another brass horn. On this plastic horn I feel as if I am continually creating my own sound. The plastic sax definitely has its own tone, although I’m convinced that Coleman would have created his own sound regardless of what kind of horn he was playing.

One of the first things that caught my attention with these two albums was the looseness—the sheer let-it-all-hang-out, almost instinctive expression that just puts it out there and knows that it will all end up hanging together somehow. To me, this is what makes even Coleman’s most boppish tunes not really sound like bebop. And it’s not just that the group is pianoless. It’s a gut approach, straight from the heart, without a drop of intellectualism or posturing. Years later, Coleman called it harmolodics: the idea that harmony, melody, rhythm, and pulse are equally important, and that the improviser plays without constraints and limits. He said, When our group plays, before we start out to play, we do not have any idea what the end result will be. Each player is free to contribute what he feels in the music at any given moment. We do not begin with a preconceived notion as to what kind of effect we will achieve. He also stressed that it was the group’s rapport that allowed the music to flow so effortlessly. Coleman’s approach to music didn’t make things easy for him when he started working as a musician. …every time I’d get a job I’d get up and someone would give me a solo and I’d just play exactly what came to me that very moment regardless of what we were playing — `Sweet Sue,’ or whatever. They’d say, wait a minute! This doesn’t match with this. You can’t do this. I was always getting fired for doing this. Early on, he played in carnival and rhythm and blues bands, and continually met with the same resistance. Once, a crowd in New Orleans smashed his horn.

The original tunes on “The Shape of Jazz to Come” include “Congeniality,” (named by Coleman to express the way a musician feels toward his audience), a jolly little number that finds Haden’s bass swinging especially hard; “Lonely Woman,” probably his best known work, a yearning, wailing four-way conversational ballad; and the frantic-tempoed “Eventually,” with Coleman’s squawking solo living up to the quip about avant-garde jazz sounding like an “atom bomb falling on a chicken coop.” Here and on every number, Higgins’ ears are on alert every minute, and he has an instant response to everything that’s going on. “Peace,” a sweet, gentle melody, finds both Coleman and Cherry at their most lyrical, while “Focus on Sanity” is ironically (purposely?) the most off-the-wall track with its unexpected phrases and tempo shifts seemingly jumping out of nowhere; and finally “Chronology,” a classic example of Coleman’s playing and a tune whose melody is more closely associated with bop than some of his other compositions.

“Change of the Century” offers “Free”—a wacky scale exercise with a little flip  on the end and a completely unstructured improvisational section. In Coleman’s own words from the liner notes: I think we got a spontaneous, free-wheeling thing going here. “Face of the Bass” features Haden first stating the happy little melody and then soloing free, while “Forerunner” has the musicians stepping into each others’ shoes, with the horns playing percussive accents, and bass and drums providing both rhythm and melody. “Bird Food” gives a nod to bop master Charlie Parker, and “Una Muy Bonita,” a “very pretty girl” in Spanish, is an easygoing theme underpinned by a rhythmic strummed bass drone by Haden. The title tune, “Change of the Century,” according to Coleman in the liner notes, …expresses our feeling that we have to make breaks with a lot of jazz’s recent past, including incorporating different musical styles from folk to classical.

on the end and a completely unstructured improvisational section. In Coleman’s own words from the liner notes: I think we got a spontaneous, free-wheeling thing going here. “Face of the Bass” features Haden first stating the happy little melody and then soloing free, while “Forerunner” has the musicians stepping into each others’ shoes, with the horns playing percussive accents, and bass and drums providing both rhythm and melody. “Bird Food” gives a nod to bop master Charlie Parker, and “Una Muy Bonita,” a “very pretty girl” in Spanish, is an easygoing theme underpinned by a rhythmic strummed bass drone by Haden. The title tune, “Change of the Century,” according to Coleman in the liner notes, …expresses our feeling that we have to make breaks with a lot of jazz’s recent past, including incorporating different musical styles from folk to classical.

Coleman definitely had a plan in mind for “Change of the Century” and “The Shape of Jazz to Come.” The titles alone tell us this. In the liner notes for the former album, he stated: …modern jazz, once so daring and revolutionary, has become, in many respects, a rather settled and conventional thing. The members of my group and I are now attempting a break-through to a new, freer conception of jazz, one that departs from all that is ‘standard’ and cliché in ‘modern’ jazz. But just how much of an impact has Coleman’s work had on jazz since then? In the thought-provoking BBC documentary “1959: The Year That Changed Jazz,” four recordings that altered the face of jazz are discussed: Coleman’s “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” Charles Mingus’ “Mingus Ah Um,” Dave Brubeck’s “Time Out,” and Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue.” Off the top of my head, I’d say that “Kind of Blue” took bebop in a cooler direction, “Time Out” predicted the blending of jazz with the music of other cultures and the unusual time signatures found in those cultures, and “Mingus Ah Um” showed us that jazz can make a political statement. But Coleman turned everything upside down. Bursting into the Five Spot that year, his performance with his quartet was nothing short of cataclysmic. Some loved it; others hated it. There was no middle ground.

Jazz critic Stanley Crouch pointed out in the documentary that the world at that time was living the “paranoia of the nuclear age—that the entire world could be blown up”. And Charlie Haden reinforced that thought by saying that it is “To play music with this urgency, this desperate urgency to make something new that’s never been before, as if you’re on the front line and you’re risking your life for every note you play.” The dead seriousness of the group forced people to change the way they thought about improvisation—either they embraced it or they didn’t. But enough apparently did to infuse jazz with a new sense of adventure and to influence other musicians, such as Eric Dolphy, David Murray, Archie Shepp, Lester Bowie and many others. “Another set of choices was provided for everybody,” said Crouch. Jazz critic Martin Williams, in his liner notes to “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” referred to Coleman’s “sublime stubbornness” in sticking to his guns and placing his groundbreaking work before the public, and rock guitarist Lou Reed said of Coleman in the BBC documentary: “He changed everything.” For the skeptics who think everything has already been said in jazz improvisation, Coleman provides the antidote: Music is the sound of your emotions. It’s your heart, it’s your feelings, it’s your belief, it’s your ability, and most of all, it’s your love. And: In music, the only thing that matters is whether you feel it or not.