When Miles Davis left the jazz scene in 1975, no one knew if he would ever return. In those pre-internet/cable days, there were very few reliable news sources when it came to jazz musicians. Rumors flew about Davis’ activity (or inactivity), the extent of his battles with sickle-cell anemia and a degenerative hip, and his ongoing problems with substance abuse. There were plenty of reports about Davis going back into the recording studios, but no new music was released. More than a few fans wished that Davis would jettison the funk-rock fusion and return to playing straight-ahead jazz; others suspected that Davis would continue to explore rock styles, but few expected—or recognized—that Davis’ return to the scene in 1980 used a pared-down funk style. Davis never won back all of his old fans, even though his 1980s music was quite accessible, including stunning versions of George Gershwin’s “My Man’s Gone Now”, his sensuous slow blues “Star People” or the child-like original “Jean-Pierre”. Surprisingly, Don Cheadle’s new film about Davis, “Miles Ahead”, takes place in 1979—near the end of Davis’ self-imposed sabbatical, but just before Davis’ triumphant return. With the exception of an odd final scene which only partially fulfills the need for coverage of Davis in the 1980s, the audience must forget any knowledge of Davis’ final decade to fully appreciate the story.

When Miles Davis left the jazz scene in 1975, no one knew if he would ever return. In those pre-internet/cable days, there were very few reliable news sources when it came to jazz musicians. Rumors flew about Davis’ activity (or inactivity), the extent of his battles with sickle-cell anemia and a degenerative hip, and his ongoing problems with substance abuse. There were plenty of reports about Davis going back into the recording studios, but no new music was released. More than a few fans wished that Davis would jettison the funk-rock fusion and return to playing straight-ahead jazz; others suspected that Davis would continue to explore rock styles, but few expected—or recognized—that Davis’ return to the scene in 1980 used a pared-down funk style. Davis never won back all of his old fans, even though his 1980s music was quite accessible, including stunning versions of George Gershwin’s “My Man’s Gone Now”, his sensuous slow blues “Star People” or the child-like original “Jean-Pierre”. Surprisingly, Don Cheadle’s new film about Davis, “Miles Ahead”, takes place in 1979—near the end of Davis’ self-imposed sabbatical, but just before Davis’ triumphant return. With the exception of an odd final scene which only partially fulfills the need for coverage of Davis in the 1980s, the audience must forget any knowledge of Davis’ final decade to fully appreciate the story.

“Miles Ahead” is not a traditional biopic. As a director and co-screenwriter, Cheadle owes more to Clint Eastwood’s Charlie Parker film “Bird” than he might care to admit, but both “Bird” and “Miles Ahead” expect the audience to come in with prior knowledge of the subject’s life. That does not mean that Cheadle has copied Eastwood’s style. The films share an elliptical approach to chronological material, but Cheadle’s film is actually more subjective than Eastwood’s. It might be called a free fantasy on the life of Miles Davis. Throughout the film, Cheadle juxtaposes time frames within the same scenes. For example, early in the film, we hear Phil Schaap’s 1979 radio tribute to Davis’ musical legacy. Schaap plays—and praises—Davis’ performances from the 1959 LP “Kind of Blue”. Davis (played by Cheadle) calls the radio station and chews out Schaap on the air for saying that Davis’ music belongs in a time capsule. He requests “Solea” from 1960’s “Sketches of Spain”, and as the music starts, Davis suddenly imagines his then ex-wife Frances (Emayatzy Corinealdi) silently beckoning him upstairs to the bedroom. From the context of the film, we can tell that this memory was from around 1958.

Cheadle and co-writer Steven Baigelman created a fictional story as counterpoint to the known facts about Davis’ life. The invented story—taking place in 1979—is a darkly comic tale of a session tape that Davis apparently stole from Columbia Records. The tape is nearly absconded by a Rolling Stone reporter (Ewan McGregor) who is trying to land an exclusive story about Davis’ comeback. An unscrupulous talent agent (Michael Stuhlbarg) with his own Davis imitator to promote (Keith Stanfield) gets his hands on the tape. Davis’ battles to get the tape back involves car chases, drugs and gun fights. However, this absurd story leads Cheadle into truly virtuoso filmmaking. When Davis goes to a boxing match to retrieve the tape from the agent, the action within the ring alternates between the actual fight and the 1960s Miles Davis Quintet in performance! Meanwhile, the 1979 version of Davis is fighting it out with the agent and his bodyguard (Brian Bowman) for possession of the tape. And while all of this is going on, Davis flashes back a dozen years to the day when Frances left him, ending their turbulent marriage. This is quite an achievement for a novice director like Cheadle, and an amazing display of the editing prowess of John Axelrad and Kayla M. Empter. The music is equally impressive as music supervisor Ed Gerrard and composer Robert Glasper jump-cut between samples of Davis’ various styles from the 1950s modal jazz through the early 1960s up-tempo re-imaginings of the same material to the hard-edged rock styles of the mid-1970s. It elegantly proves that Davis’ sound remained constant throughout his career, no matter how much the music around him changed.

Jazz fans should be very happy with the treatment of music in “Miles Ahead”. Cheadle, who played saxophone in high school, learned to play trumpet for this film. According to his trumpet double Keyon Harrold, Cheadle transcribed a number of Davis’ solos and was able to play them on trumpet. Harrold—wanting to avoid the wrath of other trumpeters who would spot mistakes in Cheadle’s fingering—composed music that would fit with the valve combinations that appeared on screen. Harrold played many of the solo passages mimed by Cheadle, but in several spots, Davis’ original recordings appear on the soundtrack (and unlike Eastwood’s film, the original sidemen are also present). Since there was such care taken to get the music right, the film’s final scene seems wrong. Right before the scene, Davis abruptly leaves the interview with the Rolling Stone reporter. The reporter calls to Davis, “Are you coming back?” and off-screen, Davis replies “You better believe it!” It would have made sense to replicate Davis’ 1980s style, using musicians like saxophonist Bill Evans, guitarist Mike Stern and bassist Marcus Miller. Instead, the onstage group is an odd combination of Davis alumni (Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter) and musicians who never played with Davis (Antonio Sanchez, Gary Clark, Jr., Esperanza Spalding and Glasper). A hashtag sewn onto Davis’ jacket indicates that the music is happening in the present (and the intentional omission of Davis’ death date at the end reinforces the idea). While the music is related to Davis’ 1980s style, it seems to be a fantasy for the younger musicians and Cheadle, rather than any sort of realistic portrayal (Miles Davis would have turned 90 in 2016; could we really expect that he could have continued playing trumpet at that age?)

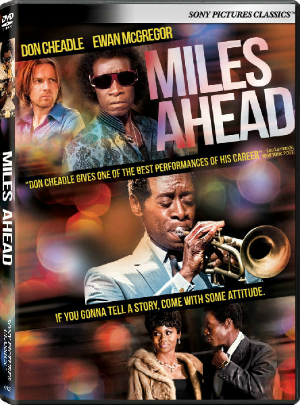

With the exception of the final scene, “Miles Ahead” is an artistically successful film and it should garner Oscar nominations for its superb acting, and its remarkable film and music editing, not to mention its extraordinarily well-crafted screenplay. The film is now available on a Sony DVD, with an outstanding Dolby Digital soundtrack, fine video resolution, and a pair of well-made supplementary features.