Between Mars and Jupiter, in a vast belt of orbiting space rocks, lives Asteroid 6083. It is relatively small—only about 3 miles across—and has a slightly eccentric orbit. Discovered in 1984, Asteroid 6083 disappeared from view for nearly five years. Since it came back into view, however, it has been spotted by observatories all over the Earth. This little asteroid has a further distinction: for the last few years it has been known by another name, one of a jazz musician. Asteroid 6083 is now known as “janeirabloom.” The name fits well. Jane Ira Bloom is physically small (one critic said that she was barely twice as tall as her soprano saxophone), never takes the easiest musical route, and—due to periods between recording contracts—has sometimes dropped out of sight of the jazz public.

Asteroids are usually renamed for astronauts, scientists and astronomers, but rarely for jazz musicians. However, Jane Ira Bloom has had a special relationship with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. In 1988, she was the first musician named to the NASA Arts Program, and over the next few years, she composed several pieces inspired by space exploration. Twenty years later, “Most Distant Galaxy” is still part of Bloom’s concert repertoire. The video below features Bloom’s soprano sax with bass and drums, but all of the sounds not normally associated with those instruments comes from Bloom, through the physical movement of her horn, and a foot-switch operated network of processors she calls “live electronics”. The electronics, turned off and on as part of the improvisation, act as an enhancement of her rich soprano sound.

Bloom refers to her music as “jazz without a safety net”. Her roots lie deep within the jazz tradition, but her adventurous spirit lets her create music from a wide range of influences. Modern art is one of her most pervasive influences, and she has performed several concerts in art galleries, sometimes playing in front of the paintings which inspired the music. She has composed and performed music for the Pilobolus dance company, and her scores grace the soundtracks of Judy Dennis’ “The Dancer Films”. Her long-standing love of sports has yielded compositions like “NFL”, which recreates a football game—complete with marching band, “The Race”, inspired by drag racer Shirley Muldowney, and the elegant tango “Ice Dancing”, dedicated to British skating duo Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean. She has also combined her original lines with standards as in “Nearly Summertime” where her angular line sets up a pervasive (and heat-inducing) 6/4 reading of the Gershwin melody.

If there is one factor that unites all these diverse musical worlds, it is the sound of Jane Ira Bloom’s soprano saxophone. It combines a full-throated classical sound with the intense lyricism of a jazz vocalist. And like the English jazz singer Norma Winstone, Bloom’s invitin g warm sound cushions the impact of her daring improvisations. When Bloom first recorded with live electronics, the warmth of her sound vanished amidst all of the digital equipment; in recent years, she has reverted to analog boxes to reduce the difference between her acoustic and electronic sounds.

g warm sound cushions the impact of her daring improvisations. When Bloom first recorded with live electronics, the warmth of her sound vanished amidst all of the digital equipment; in recent years, she has reverted to analog boxes to reduce the difference between her acoustic and electronic sounds.

Born in Boston to what she calls “a musically appreciative family”, Bloom picked up the soprano saxophone because “it seemed a natural thing to do.” She studied with Joe Viola and George Coleman, and credits Viola with giving her a deep appreciation for the soprano saxophone (“He had such a special feeling for the instrument”). She did her undergraduate and graduate studies at Yale University and in 1977, became the first non-clarinetist to receive a Master’s in saxophone performance from that institution. While at Yale, she met her husband, actor/director Joe Grifasi, and the couple moved to New York after completing their degrees. While Grifasi launched his career with appearances in films like “The Deer Hunter”, “Still of the Night”, “Splash” and “Moonstruck”, Bloom created her own record label, Outline, and worked as a sideperson with several artists, including vibraphonist David Friedman and vocalist Jay Clayton. In the early 1980s, she was filmed with Clayton and her own group for the A&E series, “Women in Jazz” and the nationwide exposure helped boost her career.

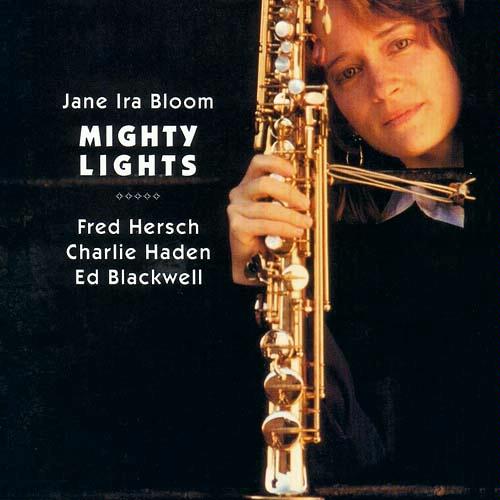

In 1982, Bloom recorded the seminal album “Mighty Lights”. Recorded for the German Enja label and later reissued through Rhino, the album had better distribution than her first two albums on Outline, and it still stands as one of her finest early achievements. On this album, Bloom leads a quartet featuring free jazz titans Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell. Haden and Blackwell play magnificently as usual, but in retrospect, the key point of interest was Bloom’s collaboration with pianist Fred Hersch. This was his first recorded meeting with Bloom, and their spiritual empathy sounds like a modern-day version of Billie Holiday and Lester Young. Bloom and Hersch work closely without ever getting in each others way. There is a healthy exchange of ideas that never turns into mere imitation. And more importantly, they show how two sensitive artists can combine their talents to create a powerful emotional statement. There are examples of their great musical unity throughout the album, but it is most apparent on “Lost in the Stars,” where Hersch’s accompaniment helps Bloom create one of her most compelling ballad readings.

create a powerful emotional statement. There are examples of their great musical unity throughout the album, but it is most apparent on “Lost in the Stars,” where Hersch’s accompaniment helps Bloom create one of her most compelling ballad readings.

It is not hard to see why I am so fascinated by “Lost in the Stars”. Bloom and Hersch take this song, one of Kurt Weill’s most haunting creations and imbue it with a sense of dramatic urgency that evokes the spirit of the unheard lyric. Hersch starts with an introduction which seems suspended in space, and then Bloom enters with the melody. She starts quietly and tenderly, caressing each note. It becomes clear that she is hearing the lyrics in her head as she plays. As the lyrics grow more intense, her playing becomes more passionate, only to relax again at the end of the chorus. Hersch takes over from where Bloom left off. He seems to know what she has in mind for her climactic solo and so he uses his half-chorus solo as a bridge to set up her statement. His spot is peaceful and reflective, peaking briefly and concluding with an engaging triplet figure. Bloom picks up the triplet figure and begins to move it upward stepwise, increasing the tension. At first, Hersch follows Bloom’s idea, then uses his skill as an accompanist to punctuate her towering statement. As her ideas continue to rise in pitch, Bloom’s sound becomes more and more imploring. She approaches the peak of her statement with an impetuous rising melodic pattern and then scales the top with a dramatic descending arpeggio. Then she takes the motive up scalewise to build the tension again, peaking this time with an impassioned return to the melody. Then, just as quickly as it peaked, the performance quiets down again, and the performance ends with a slight remembrance of Hersch’s introduction.

One of the elements that makes “Lost in the Stars” so memorable is the strong connection between the composition and the improvisation. In Bloom’s music, improvising a solo is more than just creating a new melody over the chord structure; rather, it is essential to enhance the overall mood of the composition through improvisation. And while Bloom has thorough training in the traditional composition methods of developing and manipulating motives, she finds that most of her compositions stem from her recorded improvisations. The result is a free-flowing continuum between written and extemporized material that creates music with astonishing cohesiveness and unity.

When Bloom and Hersch collaborated on the 1984 duet album, “As One”, they performed a wide range of pieces and displayed how the composition/improvisation continuum worked in each situation. The album’s opener, Bloom’s “Waiting for Daylight” is a particularly enlightening example of this approach. Hersch’s opening harp-like arpeggios evoke visions of the sky just before sunup as the night stars begin to fade. Bloom enters with the composed tune, a longing melody which echoes the anticipation of the new day while bidding farewell to the night. Her improvisation builds along the same lines as “Lost in the Stars” with the feeling of anticipation growing as her lines move higher in pitch and intensity. The solo builds to a magnificent climax as the sun finally comes up, with Hersch providing a lovely rippling effect in the high treble range. Hersch’s solo revels in the warmth of the glistening sun, steadily building in dynamics until the restatement of the theme.

begin to fade. Bloom enters with the composed tune, a longing melody which echoes the anticipation of the new day while bidding farewell to the night. Her improvisation builds along the same lines as “Lost in the Stars” with the feeling of anticipation growing as her lines move higher in pitch and intensity. The solo builds to a magnificent climax as the sun finally comes up, with Hersch providing a lovely rippling effect in the high treble range. Hersch’s solo revels in the warmth of the glistening sun, steadily building in dynamics until the restatement of the theme.

Hersch’s “Janeology” is a piece that the pianist has recorded several times, but it has never been as perfectly realized as on “As One”. The performance begins with Bloom and Hersch playing an almost pointillistic theme in unison. Then Bloom begins to improvise alone, playing short, jabbing ideas which mirror the phrases of the tune. Eventually, Hersch joins in with answering single lines. As the performance progresses, the improvised ideas get longer and begin to overlap. And then as Bloom goes into her final bars of improvisation, it suddenly becomes clear that the two have not been playing random free form ideas, but an intelligent set of exchanges over a standard harmonic progression (Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation,” if you’ve been wondering). The theme returns, now with its harmonic underpinnings intact and the duo finishes things off with a charming, underplayed coda.

During the mid-1980s, Bloom began experimenting with live electronics. Kent McLagen, who played bass on Bloom’s Outline albums, worked as an electrical engineer, and he created a velocity sensing device that let Bloom add tones based on the speed and direction she swung her soprano. Bloom included McLagen’s invention, dubbed the “Gizmo”, and a number of digital delays and harmonizers in her original setup. While the sounds were sometimes harsh and grating, they were important elements of Bloom’s recordings for Columbia and her work with NASA. “Cagney”, a saucy tribute to the legendary hoofer was recorded on Bloom’s first Columbia album, “Modern Drama”. Essentially an acoustic performance, Bloom adds the harmonizer on fast upward runs to simulate the dancer’s leaps in space. “Blues on Mars”, from the next album, “Slalom”, is an Ornette Coleman-inspired composition. Unlike most of her electronic pieces, the gadgets are on throughout the performance, and while there are more effects here than on “Cagney”, Bloom still makes them an enhancement of her basic sound. Hersch is again the pianist, and he plays an active role as he interacts with Bloom’s improvisation. To Bloom’s credit, she doesn’t let the electronics get in the way. “16 Sunsets”, a NASA piece composed and performed after Bloom’s Columbia contract lapsed, combined Bloom’s electronically enhanced saxophone with antiphonal wind ensemble. The piece was inspired by astronaut Joseph Allen’s observation that when orbiting Earth, one experienced 16 unique sunrises and sunsets per day. The score calls for the wind ensemble to move their instruments in choreographed movement and to perform intricate unison lines with Bloom.

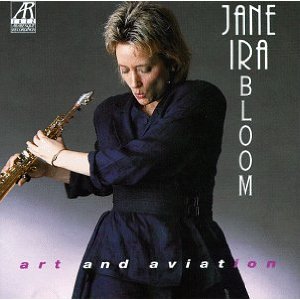

Bloom signed with the adventurous Arabesque label in 1992, and on her first CD, the aptly-titled “Art and Aviation”, the focus is clearly on Bloom’s “space” compositions. Space takes on a double meaning in these works, due to the subject matter and the deliberate paring down of the harmonic background. Many of the improvisations are either free or occur over a single chord. However, the music is never monotonous, due to the melodic talents of trumpeter Kenny Wheeler and bassists Michael Formanek and Rufus Reid, and the tasteful use of electronics by Bloom and drummer Jerry Granelli. And indeed, the electronics are now tasteful. On the opening cut, “Gateway to Progress,” the electronics are added in the middle of her solo as a natural part of the musical development. Only on the title cut do the electronic sounds get in the way of the music (and that’s mostly due to the addition of jet engines whooshing between the speakers). Granelli’s “elektro-acoustic” percussion acts as a great counterpoint to Bloom’s live electronics. For the most part, Granelli’s electronic sounds are grounded in percussion, with sounds of anvils, choked chimes, steel drums and the like. The electronic duet on “Miro” features Bloom and Granelli creating a plethora of sounds, yet it is very clear who is producing what. But on “Most Distant Galaxy”, Granelli changes the settings to a synthesized keyboard sound, allowing him to play full chords on his drums. Balancing the electronic pieces are several marvelous acoustic works. “I Believe Anita,” inspired by the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings, is an angry, slashing piece of post-bop, inspiring fiery solos by Bloom and Wheeler. “Oshumare” is the complete opposite, a lush atmospheric piece based on a vamp which modulates during the solos (Pianist Kenny Werner, featured on only two cuts on the disc, makes his presence known here with wonderful comping and a beautifully formed solo). The CD closes with a beautiful solo version of “Lost in the Stars” intended as a tribute to the recently departed Ed Blackwell.

electronics are now tasteful. On the opening cut, “Gateway to Progress,” the electronics are added in the middle of her solo as a natural part of the musical development. Only on the title cut do the electronic sounds get in the way of the music (and that’s mostly due to the addition of jet engines whooshing between the speakers). Granelli’s “elektro-acoustic” percussion acts as a great counterpoint to Bloom’s live electronics. For the most part, Granelli’s electronic sounds are grounded in percussion, with sounds of anvils, choked chimes, steel drums and the like. The electronic duet on “Miro” features Bloom and Granelli creating a plethora of sounds, yet it is very clear who is producing what. But on “Most Distant Galaxy”, Granelli changes the settings to a synthesized keyboard sound, allowing him to play full chords on his drums. Balancing the electronic pieces are several marvelous acoustic works. “I Believe Anita,” inspired by the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings, is an angry, slashing piece of post-bop, inspiring fiery solos by Bloom and Wheeler. “Oshumare” is the complete opposite, a lush atmospheric piece based on a vamp which modulates during the solos (Pianist Kenny Werner, featured on only two cuts on the disc, makes his presence known here with wonderful comping and a beautifully formed solo). The CD closes with a beautiful solo version of “Lost in the Stars” intended as a tribute to the recently departed Ed Blackwell.

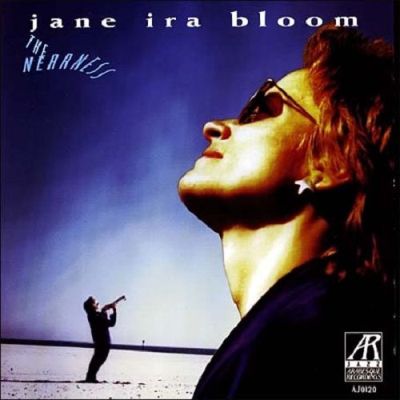

Bloom’s next Arabesque album, “The Nearness”, reverses the programming strategy of “Art and Aviation”. Here, the emphasis is  on ballads (both standards and originals), with a few adventurous works added in. Using her working sextet (Wheeler, trombonist Julian Priester, Hersch, Reid and drummer Bobby Previte), Bloom utilizes the tonal palette in remarkable ways. She uses the “player pool” concept by using the full sextet for four of the tunes, and creating different combinations for the other selections (The expected groupings of quartet and quintet are used, but “White Tower” uses the entire group except drums for a remarkable effect). Also, to make the best use of the limited solo space, Bloom has all of the horns improvise together on “Nearly Summertime” and dovetails the solos on the free-form “Panosonic.” “The All-Diesel Kitchen of Tomorrow” (what a great title!) has Bloom creating wild Doppler effects over a funky 10-beat vamp played by Priester and Reid. Yet for all of the greatness in its parts, “The Nearness” does not work well as an album. The up-tempo pieces, while superb, break the mood set up by the ballads. To cite the most extreme case, the tango “Wing Dining” opens with a boisterous introduction that has nothing to do with what follows, and seems to exist only for shock value. While “The Nearness” is conceivably a good introduction to Bloom’s music, the programming makes the total effect rather jarring.

on ballads (both standards and originals), with a few adventurous works added in. Using her working sextet (Wheeler, trombonist Julian Priester, Hersch, Reid and drummer Bobby Previte), Bloom utilizes the tonal palette in remarkable ways. She uses the “player pool” concept by using the full sextet for four of the tunes, and creating different combinations for the other selections (The expected groupings of quartet and quintet are used, but “White Tower” uses the entire group except drums for a remarkable effect). Also, to make the best use of the limited solo space, Bloom has all of the horns improvise together on “Nearly Summertime” and dovetails the solos on the free-form “Panosonic.” “The All-Diesel Kitchen of Tomorrow” (what a great title!) has Bloom creating wild Doppler effects over a funky 10-beat vamp played by Priester and Reid. Yet for all of the greatness in its parts, “The Nearness” does not work well as an album. The up-tempo pieces, while superb, break the mood set up by the ballads. To cite the most extreme case, the tango “Wing Dining” opens with a boisterous introduction that has nothing to do with what follows, and seems to exist only for shock value. While “The Nearness” is conceivably a good introduction to Bloom’s music, the programming makes the total effect rather jarring.

The 1999 release, “The Red Quartets” revisits the composition/improvisation continuum and expands these ideals into larger forms. The opening track, “Always Hope,” starts with Hersch playing a rhythmic figure that could be either in 3/4 or 4/4 time. The  rhythmic ambiguity continues as Bloom, bassist Mark Dresser and Previte enter, each with a different concept of the time. It isn’t until a minute or so into the track that the beat is stated clearly, and like an evolving organism, the quartet moves in and out of explicit timekeeping for the remainder of the track. Yet once the listener has the time in his head, it is never lost, no matter what the band states. Such a concept could easily fall flat, but the remarkable communication between the quartet members makes the piece soar. “Emergency” also depends on the group to create the compositional form. Opening with a dramatic line played by sax, piano and bass, the lines begin to overlap and they gradually develop into a violent free section. But then, one by one, instruments drop out until Dresser is alone on bass. Previte eventually joins in with a simple pattern, and when Bloom returns, she is surprisingly calm. Over the next few minutes, the intensity slowly increases so that the return to the theme and its corresponding violence is a natural extension of what came before. For fans of “As One”, there is a Bloom/Hersch duet on “Time After Tjme”, and both “Chagall” (Bloom’s introduction to “How Deep Is The Ocean?”) and “Five Full Fathoms” utilize the inside-the-piano strumming effects found on “As One”’s sound-piece, “Inside.” Mark Dresser, who played on several of Bloom’s later albums, displays flawless intonation throughout the album and his interplay with the other quartet members on “Monk’s Rec Room” makes it sound as if he’d been recording with them for years. And on Bloom’s Mingus-esque composition, “It’s A Corrugated World” he re-creates the fingernail-plucked sound heard on the Ellington/Mingus/Roach “Monev Jungle” album.

rhythmic ambiguity continues as Bloom, bassist Mark Dresser and Previte enter, each with a different concept of the time. It isn’t until a minute or so into the track that the beat is stated clearly, and like an evolving organism, the quartet moves in and out of explicit timekeeping for the remainder of the track. Yet once the listener has the time in his head, it is never lost, no matter what the band states. Such a concept could easily fall flat, but the remarkable communication between the quartet members makes the piece soar. “Emergency” also depends on the group to create the compositional form. Opening with a dramatic line played by sax, piano and bass, the lines begin to overlap and they gradually develop into a violent free section. But then, one by one, instruments drop out until Dresser is alone on bass. Previte eventually joins in with a simple pattern, and when Bloom returns, she is surprisingly calm. Over the next few minutes, the intensity slowly increases so that the return to the theme and its corresponding violence is a natural extension of what came before. For fans of “As One”, there is a Bloom/Hersch duet on “Time After Tjme”, and both “Chagall” (Bloom’s introduction to “How Deep Is The Ocean?”) and “Five Full Fathoms” utilize the inside-the-piano strumming effects found on “As One”’s sound-piece, “Inside.” Mark Dresser, who played on several of Bloom’s later albums, displays flawless intonation throughout the album and his interplay with the other quartet members on “Monk’s Rec Room” makes it sound as if he’d been recording with them for years. And on Bloom’s Mingus-esque composition, “It’s A Corrugated World” he re-creates the fingernail-plucked sound heard on the Ellington/Mingus/Roach “Monev Jungle” album.

Since 1989, Bloom has been part of the music department at the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music. She oversees the jazz performance program with Reggie Workman, teaches jazz composition and coaches a student combo dedicated to the music of Ornette Coleman. Yet her stylistic focus at the New School is as wide-ranging as her own playing, for in addition to the above courses, she teaches a course in how to play ballads. Ballads are close to her heart and while she has not abandoned traditional ballad style (which she uses on her original ballads), Bloom has taken a new minimalistic approach to standards. Starting with the 2002 album, “Sometimes the Magic”, (but echoing back to the solo version of “Lost in the Stars” from “Art and Aviation”), each of Bloom’s albums has included one or two standards, most stemming from post-WWII book musicals. Bloom grew up with these songs through the original cast LPs, and her ongoing love of the material helped her develop this new ballad style. On most of her recent ballad recordings, she plays the song alone with little or no improvisation. At times, she plays with the bell pointing into the strings of the piano while the pianist holds down the damper pedal. This technique, adapted from an idea by composer George Crumb, creates a cavernous sound which combines the original sound of the saxophone with the sympathetic vibrations from the undamped piano strings. She rarely uses live electronics on standard ballads, letting the rich unaltered sound of her horn tell the story.

The calm unaccompanied standards are most welcome on “Sometimes the Magic”, where many of the original compositions have a restless, agitate d quality. Most of the album is acoustic, with Bloom offering her only use of live electronics on the sixth track, “Truth in Timbre”. The surging “Varo” revisits a composition Bloom first recorded on her debut Outline album, while the newer pieces “Denver Snap” and “Now You See It” feature tempo changes, and shifting rhythmic moods, respectively. “Many Landscapes” may have started out as a ballad, but the performance adds underlying tension through its stark interjections by Dresser and Previte. The densest point of the album (and possibly in Bloom’s entire discography) is on “Blue Poles” where Bloom overdubs lines in both channels and pans another in between. The grooving “Pacific” (whose title may refer to a mood rather than the ocean) and the ethereal sax/bass duet “Without Words” offer additional respite from the intensity of the other tracks. Pianist Vincent Bourgeyx was a member of Bloom’s quartet for five years, but he makes his only appearance on a Bloom recording here. His style seems a little conservative for this group, but he adapts well to the changing atmospheres and his solos are effective contrasts to the other members of the quartet.

d quality. Most of the album is acoustic, with Bloom offering her only use of live electronics on the sixth track, “Truth in Timbre”. The surging “Varo” revisits a composition Bloom first recorded on her debut Outline album, while the newer pieces “Denver Snap” and “Now You See It” feature tempo changes, and shifting rhythmic moods, respectively. “Many Landscapes” may have started out as a ballad, but the performance adds underlying tension through its stark interjections by Dresser and Previte. The densest point of the album (and possibly in Bloom’s entire discography) is on “Blue Poles” where Bloom overdubs lines in both channels and pans another in between. The grooving “Pacific” (whose title may refer to a mood rather than the ocean) and the ethereal sax/bass duet “Without Words” offer additional respite from the intensity of the other tracks. Pianist Vincent Bourgeyx was a member of Bloom’s quartet for five years, but he makes his only appearance on a Bloom recording here. His style seems a little conservative for this group, but he adapts well to the changing atmospheres and his solos are effective contrasts to the other members of the quartet.

Bloom’s final album for Arabesque was “Chasing Paint: Jane Ira Bloom Meets Jackson Pollock”. While the meeting is purely artistic (Bloom was about a year old when Pollock died in an auto accident), there is plenty of empathy between the two artists. Bloom’s emotional solo on the opening track, “Unexpected Light” seems to call out to Pollock beyond the trappings of time and space, while Dresser and Previte set up an irresistible groove behind Fred Hersch’s piano solo. Once again, the improvisations maintain and enhance the moods of Bloom’s original compositions. Many of Bloom’s serpentine melody lines recall Pollock’s unpredictable paint drippings, and several of the pieces feature simultaneous improvising to simulate Pollock’s bold meshing of colors. Bloom’s composition “Jackson Pollock” was inspired by the painting “Autumn Rhythm 1950”. Pollock’s 207-inch wide canvas features a mass of swirling, looping, overlapping patterns. Bloom’s tribute uses three instruments, echoing the three colors of the painting: black, white and tan. Her original 1980 recording featured soprano sax, vibes and bass, but on “Chasing Paint”, Bloom substitutes Previte’s drums for the vibes. The piece opens with Bloom performing the brief rubato theme alone, adding the other instruments on the following statement of the theme. As the piece moves into the improvised section, there is never a stated pulse, but the musicians skillfully interweave their lines just as Pollock did in his painting. Bloom introduces live electronics in the second half of her solo. The effects emphasize Bloom’s arching melodic lines, and the effects change with astonishing frequency, moving between an octave doubler and a harmonizer. Near the end of the next track, “Alchemy”, Bloom’s solo cadenza offers a dazzling display of her electronic wizardry, with several devices used simultaneously.

on the opening track, “Unexpected Light” seems to call out to Pollock beyond the trappings of time and space, while Dresser and Previte set up an irresistible groove behind Fred Hersch’s piano solo. Once again, the improvisations maintain and enhance the moods of Bloom’s original compositions. Many of Bloom’s serpentine melody lines recall Pollock’s unpredictable paint drippings, and several of the pieces feature simultaneous improvising to simulate Pollock’s bold meshing of colors. Bloom’s composition “Jackson Pollock” was inspired by the painting “Autumn Rhythm 1950”. Pollock’s 207-inch wide canvas features a mass of swirling, looping, overlapping patterns. Bloom’s tribute uses three instruments, echoing the three colors of the painting: black, white and tan. Her original 1980 recording featured soprano sax, vibes and bass, but on “Chasing Paint”, Bloom substitutes Previte’s drums for the vibes. The piece opens with Bloom performing the brief rubato theme alone, adding the other instruments on the following statement of the theme. As the piece moves into the improvised section, there is never a stated pulse, but the musicians skillfully interweave their lines just as Pollock did in his painting. Bloom introduces live electronics in the second half of her solo. The effects emphasize Bloom’s arching melodic lines, and the effects change with astonishing frequency, moving between an octave doubler and a harmonizer. Near the end of the next track, “Alchemy”, Bloom’s solo cadenza offers a dazzling display of her electronic wizardry, with several devices used simultaneously.

Since the end of her Arabesque contract, Bloom has gone back into the realm of self-production. She has purchased the rights to her Arabesque albums and reissued them on her revitalized Outline label. Before she started recording new albums for Outline, she recorded one album for ArtistShare. For “Like Silver, Like Song”, Jamie Saft took over the keyboard chair, performing on piano, Wurlitzer, Fender Rhodes and various synthesizers. Previte’s drums are also electrified, so with Bloom’s electronics added to the mix, Dresser is the only musician who plays acoustic throughout the CD! Nearly all of the music is new, and the combination of the electronics makes the sound dense and potentially inaccessible for listeners new to Bloom’s music. While there are traditional-sounding moments within the 61-minute continuous program, it is quite challenging to sift through the keyboard sounds (which sometimes sounds like a mashup between musique concréte and 1970s video games) and Bloom’s dazzling (but sometimes overwhelming) live electronics. This might be considered advanced level Jane Ira Bloom: not a good introduction, but interesting for those who know and understand her earlier work.

Since the end of her Arabesque contract, Bloom has gone back into the realm of self-production. She has purchased the rights to her Arabesque albums and reissued them on her revitalized Outline label. Before she started recording new albums for Outline, she recorded one album for ArtistShare. For “Like Silver, Like Song”, Jamie Saft took over the keyboard chair, performing on piano, Wurlitzer, Fender Rhodes and various synthesizers. Previte’s drums are also electrified, so with Bloom’s electronics added to the mix, Dresser is the only musician who plays acoustic throughout the CD! Nearly all of the music is new, and the combination of the electronics makes the sound dense and potentially inaccessible for listeners new to Bloom’s music. While there are traditional-sounding moments within the 61-minute continuous program, it is quite challenging to sift through the keyboard sounds (which sometimes sounds like a mashup between musique concréte and 1970s video games) and Bloom’s dazzling (but sometimes overwhelming) live electronics. This might be considered advanced level Jane Ira Bloom: not a good introduction, but interesting for those who know and understand her earlier work.

For her next  CD, “Mental Weather”, Bloom brought in an entirely new rhythm section. The witty and creative Matt Wilson played drums and percussion, Mark Helias (who occasionally works with Mark Dresser) came in on bass, and the Seattle-based Dawn Clement (seen in the photo below with Bloom) filled the piano chair. Clement is a great addition to Bloom’s quartet. On the title track, Clement follows every turn of Bloom’s electrified solo, and then contributes her own solo that establishes a new direction for the music. And on Bloom’s original ballads, “A More Beautiful Question” and “Cello on the Inside”, Clement displays a rich tone and sensitive touch that enriches Bloom’s soulful melodies and improvisations. Helias has a gorgeous sound, especially when working with the bow, and his note choices are always right and in tune. Wilson’s beat on “Ready for Anything” is a marvel. Played almost entirely on a pair of antique cymbals with isolated notes played on a glockenspiel, Wilson creates a sound that balances between progressive and straight-ahead jazz. And indeed, this entire album seems to find that middle ground, using loose rhythmic

CD, “Mental Weather”, Bloom brought in an entirely new rhythm section. The witty and creative Matt Wilson played drums and percussion, Mark Helias (who occasionally works with Mark Dresser) came in on bass, and the Seattle-based Dawn Clement (seen in the photo below with Bloom) filled the piano chair. Clement is a great addition to Bloom’s quartet. On the title track, Clement follows every turn of Bloom’s electrified solo, and then contributes her own solo that establishes a new direction for the music. And on Bloom’s original ballads, “A More Beautiful Question” and “Cello on the Inside”, Clement displays a rich tone and sensitive touch that enriches Bloom’s soulful melodies and improvisations. Helias has a gorgeous sound, especially when working with the bow, and his note choices are always right and in tune. Wilson’s beat on “Ready for Anything” is a marvel. Played almost entirely on a pair of antique cymbals with isolated notes played on a glockenspiel, Wilson creates a sound that balances between progressive and straight-ahead jazz. And indeed, this entire album seems to find that middle ground, using loose rhythmic  grooves as a foundation with adventurous improvisation on top. Bloom is especially good at sculpting free-flowing lines over a ground beat, and her ecstatic solo on “Luminous Bridges” should be required listening for any musician who feels rhythmically trapped when playing against a funk groove. As on “Like Silver, Like Song”, “Mental Weather” includes an alternative mix and edit of the entire album as a single, continuous MP3 file.

grooves as a foundation with adventurous improvisation on top. Bloom is especially good at sculpting free-flowing lines over a ground beat, and her ecstatic solo on “Luminous Bridges” should be required listening for any musician who feels rhythmically trapped when playing against a funk groove. As on “Like Silver, Like Song”, “Mental Weather” includes an alternative mix and edit of the entire album as a single, continuous MP3 file.

Bloom’s latest CD, “Wingwalker” follows in the same direction as “Mental Weather”. Clement, Helias and Previte are onboard, and the unity of the rhythm section is stunning, regardless of whether they work from a stated ground beat or play in free time. Bloom uses the live electronics on nearly every track, and while her electronic improvisations are as brilliant as ever, the compositions work equally well in a purely acoustic setting (as proved in a recent concert at the University of Colorado). While “Wingwalker” has a wide range of material, including several original ballads (“Her Exacting Light”, “Ending Red Songs” and “Adjusting to Midnight”) and complex post-bop workouts (“Airspace” and “Rookie”), many of the pieces freely mix styles including the blues “Freud’s Convertible” and the atmosph eric-then-grooving “Frontiers in Science”. The quartet makes these stylistic changes effortlessly and they seem to flow as a natural extension of the compositions. The music on “Wingwalker” is denser than “Mental Weather’ but it is no less accessible. The MP3 attachment condenses the 57-minute album into 5 minutes and 49 seconds, and Bloom writes that it reminds her of the singularity concept in astrophysics where spacetime is completely altered. How many jazz musicians have that concept at their fingertips?

eric-then-grooving “Frontiers in Science”. The quartet makes these stylistic changes effortlessly and they seem to flow as a natural extension of the compositions. The music on “Wingwalker” is denser than “Mental Weather’ but it is no less accessible. The MP3 attachment condenses the 57-minute album into 5 minutes and 49 seconds, and Bloom writes that it reminds her of the singularity concept in astrophysics where spacetime is completely altered. How many jazz musicians have that concept at their fingertips?

When asked about future collaborators, Bloom took a few weeks to answer, but she came up with some rather surprising answers. She said she’d love to play behind Aretha Franklin. In her many years of freelance gigs, Bloom has recorded with several vocalists including Ethel Ennis, Cleo Laine and Jay Clayton. I suspect that Bloom could add some intriguing improvisations behind Franklin and I’ll bet that she would dig Bloom’s deliciously funky grooves, too. Bloom also said she’d like to play a duet with Jim Hall, and that would fit well within another future project of hers: an all-ballads concert featuring her quartet. This concert would be a great showcase for Bloom, as it could include both original pieces and standards, played in solo, duet and quartet formats. And as a recording, it would be an accessible (and probably challenging) introduction for many new fans. If anyone could sustain interest within such a concept, it would be Jane Ira Bloom. She is a master storyteller, whether the story takes place in an intimate room, a dance studio, an art gallery or in outer space.

Copyright Thomas Cunniffe

This article has appeared in different forms in the Jazz Heritage Foundation Jazz Journal and on the website of the Jazz Institute of Chicago.

Many thanks to Jane Ira Bloom for years of friendship and collaboration.