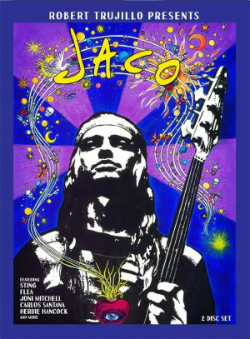

Jaco Pastorius was an anomaly in jazz. He was the most technically proficient electric bassist in the music’s history, but because the instrument has generally fallen out of favor in jazz circles (with the notable exceptions of Bob Cranshaw and Steve Swallow), most of Pastorius’ influence has appeared within rock groups. Partially as a result of this cross-genre influence, the first major documentary on Pastorius, “Jaco”, was produced by Robert Trujillo of the heavy metal band Metallica. The film, which was authorized by Pastorius’ family, portrays Jaco as a virtuoso musician, devoted family man and at the end, a tragic victim of bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Director Paul Marchand draws on several vintage Pastorius interviews, plus a wide range of Pastorius’ family members, friends, colleagues and admirers to explore the bassist’s short but tumultuous life.

Jaco Pastorius was an anomaly in jazz. He was the most technically proficient electric bassist in the music’s history, but because the instrument has generally fallen out of favor in jazz circles (with the notable exceptions of Bob Cranshaw and Steve Swallow), most of Pastorius’ influence has appeared within rock groups. Partially as a result of this cross-genre influence, the first major documentary on Pastorius, “Jaco”, was produced by Robert Trujillo of the heavy metal band Metallica. The film, which was authorized by Pastorius’ family, portrays Jaco as a virtuoso musician, devoted family man and at the end, a tragic victim of bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Director Paul Marchand draws on several vintage Pastorius interviews, plus a wide range of Pastorius’ family members, friends, colleagues and admirers to explore the bassist’s short but tumultuous life.

Pastorius’ grew up in South Florida, and the film shows him as a young prodigy as singer, drummer and bassist. His father was a classic pop singer, and when Jaco was still a toddler, he was brought on stage where he sang all of the songs from Frank Sinatra’s “Come Fly with Me” LP. Later, with money earned from a paper route, he bought a set of drums, and a few years later, changed to bass, first taking up the acoustic but changing to electric when his bass fiddle broke apart due to the humid climate. Jaco claimed that he started playing gigs on the day he bought the electric bass, and some of his early colleagues said that he learned how to read music within a few years. He married his high school sweetheart, and became a father within a few years. The birth of his daughter inspired him to be more than just a working musician, but a virtuoso. After sitting in with Blood, Sweat and Tears, drummer Bobby Colomby invited him to record for Epic Records. Pastorius was so proud of his eponymous debut album that he literally pushed it into the face of Weather Report’s Joe Zawinul. While Zawinul brushed off Pastorius at first, he later invited Pastorius to join the band. The relationship between the two men was sometimes tempestuous, with Pastorius acting like a son begging for his father’s approval. At other times, they were quite genial towards each other (Joni Mitchell describes Joe and Jaco playing Frisbee in a recording studio). Pastorius’ fame grew to tremendous heights while with Weather Report, leading to impressive sideman appearances on albums by Mitchell and Ian Hunter. Pastorius, who was already promoting himself as “the world’s greatest electric bassist” before joining Weather Report, became more and more extroverted on stage, playing extended solos which sometimes ended with him throwing his bass in the air. When he left Weather Report at the end of 1981, he had recorded an impressive second album as a leader, “Word of Mouth”, but the sales were less than spectacular, and Pastorius’ life took a downward spiral. His mental health became more unsteady with his use of alcohol and drugs, and he was eventually committed to Bellevue Hospital. His first marriage had fallen apart, and when his second wife gave birth to twin boys, she decided that Jaco’s lifestyle was a bad influence on the children. In his final years, he was frequently homeless and he died from a beating from a club bouncer after creating a disturbance at a Carlos Santana concert.

The film is at its best when discussing Jaco as a man. His surviving friends, including Peter Erskine, Wayne Shorter, Joni Mitchell and Bobby Thomas, all have great stories to tell about Pastorius’ personality, and his approach to life. Some of the details about Pastorius’ musical innovations and his eventual breakdown are presented as fragments, which must be assembled by the viewer. While some of the rock musicians like Sting, Flea and Bootsy Collins are fairly articulate about Pastorius’ technical abilities, many of the other rockers seem unable to make coherent statements about his music. There are also a few blatant historical mistakes in the film’s final cut. An opening (uncredited) quote states that in 1976, James Brown, Igor Stravinsky, Jimi Hendrix, Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra were all still making music; but by then, Hendrix and Stravinsky had been dead for five years, and neither Presley nor Sinatra were making their best recordings. The film also omits all references to Pastorius’ collaborations with Pat Metheny. Both men taught music at the University of Miami in the early 70s, and they recorded two early albums together, including the guitarist’s classic “Bright Size Life”. On the home video’s supplemental section, Bob Moses speaks of that session (although not by name), but despite the appearance of a track from the album on the film soundtrack, Metheny is completely ignored. The supplemental interviews also include vital information on Pastorius’ early development, as well as a revealing sound bite from Santana about the events leading to Pastorius’ death. It’s good that the interviews have been included on the DVD, but some of them truly belonged within the documentary itself.

MVD’s presentation is superb, including a 5.1 Dolby Digital sound design by Weather Report’s sound engineer, Brian Risner. The image is enhanced for 16:9 screens with the vintage clips presented in their original aspect ratio. A soundtrack album, featuring some of Pastorius’ legendary recordings, has been issued by Sony Music, and they have also recently issued a 4-CD set, “The Legendary Live Tapes” which collects sound board mixes and audience recordings of Weather Report’s tours between 1978 and 1981. This may be the best time to examine—or revisit—the music of Jaco Pastorius.