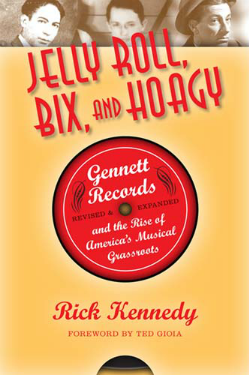

Anyone studying early jazz recordings will quickly discover the important recordings made for two small Midwestern labels, Gennett and Paramount. Both labels were subsidiaries of larger companies: Paramount was part of the Wisconsin Chair Company of Grafton, Wisconsin, and Gennett was an offshoot of the Starr Piano Company of Richmond. Indiana. While both companies did some recording in Chicago, both had their main studios attached to their home factories. Neither company was close to the Windy City (Grafton was 118 miles away, and Richmond was 265 miles away) but many early jazz and blues musicians endured the long train rides to make recordings. Initially, Gennett and Paramount were competitors, but for a short time in the late 1920s, some recordings made at Gennett’s Richmond studios were issued on Paramount. The fascinating story of Gennett Records is told in Rick Kennedy’s newly revised and expanded book “Jelly Roll, Bix and Hoagy” (University of Indiana Press). In six well-written chapters, Kennedy gives a thorough history of the company, starting with its development as a piano manufacturer and going through its rise and fall as a recording company.

Anyone studying early jazz recordings will quickly discover the important recordings made for two small Midwestern labels, Gennett and Paramount. Both labels were subsidiaries of larger companies: Paramount was part of the Wisconsin Chair Company of Grafton, Wisconsin, and Gennett was an offshoot of the Starr Piano Company of Richmond. Indiana. While both companies did some recording in Chicago, both had their main studios attached to their home factories. Neither company was close to the Windy City (Grafton was 118 miles away, and Richmond was 265 miles away) but many early jazz and blues musicians endured the long train rides to make recordings. Initially, Gennett and Paramount were competitors, but for a short time in the late 1920s, some recordings made at Gennett’s Richmond studios were issued on Paramount. The fascinating story of Gennett Records is told in Rick Kennedy’s newly revised and expanded book “Jelly Roll, Bix and Hoagy” (University of Indiana Press). In six well-written chapters, Kennedy gives a thorough history of the company, starting with its development as a piano manufacturer and going through its rise and fall as a recording company.

Today, Gennett is best remembered for its jazz recordings, and for the special records it made for hire, including several infamous sides for the Ku Klux Klan. Kennedy posits that the Gennett family had very little appreciation for any of the music they recorded, and that the recording arm was simply a way to capitalize on the boom in phonographs and records. Gennett had great talent scouts though, including Fred Wiggins who managed the Starr Piano store in Chicago. By convincing the hottest jazz bands in Chicago to record in Richmond, he secured important sessions by King Oliver’s Jazz Band, Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, the New Orleans Rhythm Kings and Hoagy Carmichael. Kennedy recounts some of the best-known stories about the Gennett studios: the stifling heat, the sessions that went on for hours, but stopped whenever a train passed, the notoriously poor sound quality of the records, and the seemingly arbitrary decisions of what was released. Kennedy also tells lesser-known tales, as in the story of the KKK rally that took place while the King Oliver band was in town to record.

While discussions of Gennett’s classic jazz recordings take up nearly half of the book, Kennedy also spends a good deal of time talking about Gennett’s other specialties: “old-time” or hillbilly music, and classic blues. He brings the same enthusiasm for these styles as he does for jazz. Indeed, the complex machinations involving producer/talent scout Dennis Taylor and country fiddler Doc Roberts are as fascinating as the stories about the jazz musicians. Kennedy also gives plenty of attention to the important blues recordings of Charley Patton, Roosevelt Sykes and Blind Lemon Jefferson. And mixed in with the various music styles are clear, easy-to-read discussions of Gennett’s business operations, including details of crucial legal battles, their impressive distribution network (including the Sears mail-order catalog) and their sometimes tardy payments of artist royalties. Kennedy also helps to decipher Gennett’s maze of artist pseudonyms (many of which were unknown to the original artists!)

Kennedy’s book was first published in 1994. I have not compared the original edition to the current one, but two areas are clearly new to this version. Best is a discussion of how the city of Richmond has embraced the history of Starr Piano and Gennett Records with a new park on the grounds of the original factory, and paintings and statues of the great musicians who recorded at Gennett. Less successful is Kennedy’s constant reiteration that most of the Gennett catalog is now available on CDs and on the internet. He seems to bring up this point on about every other page, but he never explains why these recordings are easily available. The answer is one we discussed in last month’s Benny Goodman book review: under British copyright law, all of the Gennett recordings are now in the public domain, meaning that anyone in the UK can legally issue these recordings without paying royalties. Fortunately, the collector’s label JSP has issued several superbly-remastered sets of Gennett masters, and the Archeophone label have also issued fine-sounding sets of the King Oliver and Beiderbecke/Wolverine sides. But not all of these reissue companies take the trouble to clean up the sound and correct speed problems, and that means that some of the current editions could sound worse than the original 78s! In the back of the book, Kennedy lists 50 classic Gennett sides and recommended CD reissues, but a simple explanation of the legal status of these recordings might have been more valuable to novice fans.

Despite the above caveat, Kennedy’s book comes highly recommended. His writing style is entertaining and informative. By describing the personal characteristics of Gennett’s principal owners, the reader can easily keep all of the various characters straight. Further, Kennedy’s wide-ranging appreciation for American music makes the reader want to hear these recordings. The Gennetts may not have fully appreciated the music they recorded, but Rick Kennedy makes up for that many times over.