Although they were born just seven years apart, saxophonists John Coltrane and Frank Morgan reached their artistic zeniths in the last years of their lives. Both men were enamored of Charlie Parker, and in addition to absorbing his music, they also engaged in Bird’s worst vice: heroin addiction. For both Coltrane and Morgan, their greatest musical triumphs would only happen after they got the monkeys off their backs. Each of these tremendous saxophonists are the subjects of new documentaries, and their drug addictions are handled in opposite ways: for Coltrane, a discussion of how he broke the habit is handled in rather short order so the filmmaker can focus on Trane’s greater accomplishments; for Morgan, drugs and crime take up half of the film’s running time, offering a sympathetic view of why drugs were prevalent among black musicians, harrowing tales of the effects, and surprisingly funny stories of the audacious acts Morgan and his friends would do to raise money for the daily fix.

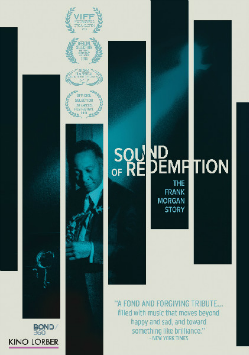

“Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story” (Kino/Lorber) follows many of the standard tropes of jazz documentaries: a parade of talking  heads, a few clips of the now-deceased subject, and a celebratory memorial concert. However, the content of the interviews and music—both current and archival—make this film extraordinary. Director N.C. Heikin tells Morgan’s story in basic chronological order. We hear tales of Morgan’s father, who was a member of the popular vocal group, the Ink Spots, catch a few typical loving quotes from his mother, and learn of Morgan’s early ascendancy as a jazz musician. Yet, in a brilliant turn, Heikin doubles back on the story a half-hour later, revealing that Morgan’s mother was a prostitute who, on several occasions, tried to kill Frank before he was born, and that Morgan’s father was acting as her pimp. When Morgan was six years old, his parents went on the road (with his mother continuing as a sex worker) and they left their son in the care of a grandmother, who was also a madam! By this clever reveal, along with discussions of Jim Crow attitudes prevalent in late-1940s Los Angeles, we can better understand why Morgan veered toward drugs and crime. As noted above, Morgan’s greatest recordings came after he stopped taking drugs and he left prison. In his interviews, Morgan seems unrepentant at times, but his music hits the listener hard with its raw and deep emotions. The contemporary concert was filmed at San Quentin, where Morgan spent “a life sentence on the installment plan”. The front line of alto saxophonist Mark Gross and trombonist Delfeayo Marsalis raise the roof with an exciting sequence of exchanges on Dizzy Gillespie’s “The Champ”, but the highlight of the concert comes when alto saxophonist Grace Kelly silences the audience with her heart-breaking performance of “Over the Rainbow”. Kelly starts by playing the verse unaccompanied, then on the chorus, the rhythm section of George Cables (piano), Ron Carter (bass) and Marvin “Smitty” Smith (drums) enters one by one. When the song ends, we see many of the audience members (including Morgan’s ex-wife and half-sister) wiping away tears. Frank Morgan, who mentored Kelly when she was a teenaged prodigy (much like himself), may have wasted away much of his life doing drugs and spending time in prison, but judging by the quality of his own music, and that of his very talented protégée, we can almost forgive him for his many misdeeds.

heads, a few clips of the now-deceased subject, and a celebratory memorial concert. However, the content of the interviews and music—both current and archival—make this film extraordinary. Director N.C. Heikin tells Morgan’s story in basic chronological order. We hear tales of Morgan’s father, who was a member of the popular vocal group, the Ink Spots, catch a few typical loving quotes from his mother, and learn of Morgan’s early ascendancy as a jazz musician. Yet, in a brilliant turn, Heikin doubles back on the story a half-hour later, revealing that Morgan’s mother was a prostitute who, on several occasions, tried to kill Frank before he was born, and that Morgan’s father was acting as her pimp. When Morgan was six years old, his parents went on the road (with his mother continuing as a sex worker) and they left their son in the care of a grandmother, who was also a madam! By this clever reveal, along with discussions of Jim Crow attitudes prevalent in late-1940s Los Angeles, we can better understand why Morgan veered toward drugs and crime. As noted above, Morgan’s greatest recordings came after he stopped taking drugs and he left prison. In his interviews, Morgan seems unrepentant at times, but his music hits the listener hard with its raw and deep emotions. The contemporary concert was filmed at San Quentin, where Morgan spent “a life sentence on the installment plan”. The front line of alto saxophonist Mark Gross and trombonist Delfeayo Marsalis raise the roof with an exciting sequence of exchanges on Dizzy Gillespie’s “The Champ”, but the highlight of the concert comes when alto saxophonist Grace Kelly silences the audience with her heart-breaking performance of “Over the Rainbow”. Kelly starts by playing the verse unaccompanied, then on the chorus, the rhythm section of George Cables (piano), Ron Carter (bass) and Marvin “Smitty” Smith (drums) enters one by one. When the song ends, we see many of the audience members (including Morgan’s ex-wife and half-sister) wiping away tears. Frank Morgan, who mentored Kelly when she was a teenaged prodigy (much like himself), may have wasted away much of his life doing drugs and spending time in prison, but judging by the quality of his own music, and that of his very talented protégée, we can almost forgive him for his many misdeeds.

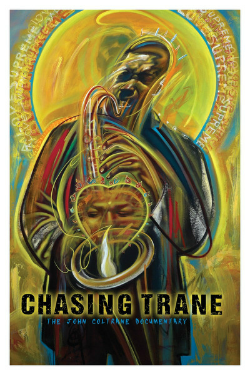

Of course, John Coltrane redeemed himself many times over during his last decade on Earth. In his film, “Chasing Trane” (Universal), writer/director John Scheinfeld advances the theory that once Coltrane freed himself of drugs, he seemed less interested in being the hottest tenor saxophonist in jazz, and more committed to concepts of space, time and the hereafter (which Sonny Rollins refers to as “the big picture”). So while we hear the familiar stories about Coltrane’s artistic triumphs in jazz (“Kind of Blue”, “Giant Steps”, “My Favorite Things”, “A Love Supreme”) there are constant reminders that Coltrane’s music was operating at a higher level. Interviewees like Dr. Cornel West and former President Bill Clinton make these larger points throughout the film (West makes a profound statement about the relationship between Martin Luther King and the saxophonist), while Coltrane’s close friends and children relate tales of Coltrane the family man and musician. Denzel Washington embodies the spirit of Coltrane as he reads excerpts from vintage interviews and liner notes, and the well-chosen film clips illustrate the ways in which the saxophonist changed his approach from year to year. When it comes to Coltrane’s final artistic period, many of the interviewees freely admit that they don’t understand the music he made with Alice Coltrane and Rashied Ali, but all realize that even after 50 years, Coltrane’s music may still be ahead of our time. Although it is not advertised as a “director’s cut”, the home video version of the film runs about 10 minutes longer than the version recently broadcast by PBS. The extra time allows for additional ruminations on Coltrane’s legacy, and a longer section on Coltrane’s 1966 appearance in Nagasaki, where the saxophonist improvised a new composition called “Peace on Earth”, dedicated to the victims of the WWII bombing. This section also introduces us to Yushiro Fujioka, whose lifelong dedication to Coltrane’s music began with this remarkable concert. The “big picture” issues are amplified in the DVD’s special features where a painter, a neurosurgeon, a group of school children and a Vietnam vet discuss how Coltrane transformed their lives, as his recordings carried an influence beyond the realm of music.

writer/director John Scheinfeld advances the theory that once Coltrane freed himself of drugs, he seemed less interested in being the hottest tenor saxophonist in jazz, and more committed to concepts of space, time and the hereafter (which Sonny Rollins refers to as “the big picture”). So while we hear the familiar stories about Coltrane’s artistic triumphs in jazz (“Kind of Blue”, “Giant Steps”, “My Favorite Things”, “A Love Supreme”) there are constant reminders that Coltrane’s music was operating at a higher level. Interviewees like Dr. Cornel West and former President Bill Clinton make these larger points throughout the film (West makes a profound statement about the relationship between Martin Luther King and the saxophonist), while Coltrane’s close friends and children relate tales of Coltrane the family man and musician. Denzel Washington embodies the spirit of Coltrane as he reads excerpts from vintage interviews and liner notes, and the well-chosen film clips illustrate the ways in which the saxophonist changed his approach from year to year. When it comes to Coltrane’s final artistic period, many of the interviewees freely admit that they don’t understand the music he made with Alice Coltrane and Rashied Ali, but all realize that even after 50 years, Coltrane’s music may still be ahead of our time. Although it is not advertised as a “director’s cut”, the home video version of the film runs about 10 minutes longer than the version recently broadcast by PBS. The extra time allows for additional ruminations on Coltrane’s legacy, and a longer section on Coltrane’s 1966 appearance in Nagasaki, where the saxophonist improvised a new composition called “Peace on Earth”, dedicated to the victims of the WWII bombing. This section also introduces us to Yushiro Fujioka, whose lifelong dedication to Coltrane’s music began with this remarkable concert. The “big picture” issues are amplified in the DVD’s special features where a painter, a neurosurgeon, a group of school children and a Vietnam vet discuss how Coltrane transformed their lives, as his recordings carried an influence beyond the realm of music.

Because of its nationwide exposure on PBS, the Coltrane documentary will doubtlessly find its way into the music libraries of many jazz fans. It is equally impressive as an introduction to Coltrane, and as a remarkable tribute to a jazz giant. However, I would also encourage all readers to seek out the Morgan film, which played in a number of theaters in the past few years and quietly slipped onto DVD earlier this year. It is an expertly-crafted film which deserves the same amount of acclaim as the Coltrane video. I have not found any previous reviews of the Morgan disc, and I only discovered it when Amazon suggested it to go with my purchase of “I Called Him Morgan” and “Chasing Trane”. Say what you will about computerized suggestions, but this time, the recommendation was right on the money.