On February 23, 1980, I was sitting in the audience at Greeley’s Foundation Hall, a converted movie theater used as a concert venue for the University of Northern Colorado’s music department. I was 18, just graduated from high school, and although I was not yet a student at UNC, I had been attending their concerts for three years. College vocal jazz groups were a fairly new phenomenon, but UNC was on the cutting edge of the movement. On that Saturday afternoon, I was attending the third annual UNC Vocal Jazz Festival. Phil Mattson was onstage critiquing a student group, and he told the group and the audience, “If you have not picked up the new Manhattan Transfer album, RUN to your nearest record store and get one!”

On February 23, 1980, I was sitting in the audience at Greeley’s Foundation Hall, a converted movie theater used as a concert venue for the University of Northern Colorado’s music department. I was 18, just graduated from high school, and although I was not yet a student at UNC, I had been attending their concerts for three years. College vocal jazz groups were a fairly new phenomenon, but UNC was on the cutting edge of the movement. On that Saturday afternoon, I was attending the third annual UNC Vocal Jazz Festival. Phil Mattson was onstage critiquing a student group, and he told the group and the audience, “If you have not picked up the new Manhattan Transfer album, RUN to your nearest record store and get one!”

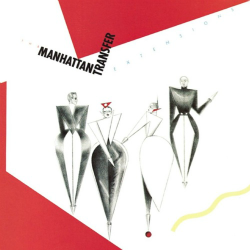

I didn’t run out that minute, but within the next two days, I took Mattson’s advice and purchased my first vinyl copy of “Extensions”. It made me a lifetime fan of the group, but I must admit to a little hesitancy when I saw the album cover. Against a white background were two dramatic re d blocks with sharply accented corners. The four figures representing the singers were heavily stylized caricatures with the legs molded into single sharp points. The photos of the group on the back cover were even stranger, featuring outer space costumes, heavy facial makeup and wild hair styles. Was this the Manhattan Transfer (usually dressed in tuxes and evening gowns) or Devo? However, when I looked at the track list, I recognized two songs that I had heard sung by college groups over the previous weekend: “Birdland” and “Shaker Song”. When I got home and played the record, I discovered that it was indeed a jazz album, and that only half of the album was futuristic and electronic. The rest was acoustic and closer to the classic sound that the Transfer had established over the previous decade.

d blocks with sharply accented corners. The four figures representing the singers were heavily stylized caricatures with the legs molded into single sharp points. The photos of the group on the back cover were even stranger, featuring outer space costumes, heavy facial makeup and wild hair styles. Was this the Manhattan Transfer (usually dressed in tuxes and evening gowns) or Devo? However, when I looked at the track list, I recognized two songs that I had heard sung by college groups over the previous weekend: “Birdland” and “Shaker Song”. When I got home and played the record, I discovered that it was indeed a jazz album, and that only half of the album was futuristic and electronic. The rest was acoustic and closer to the classic sound that the Transfer had established over the previous decade.

Looking back at “Extensions” 34 years later, it was clearly a turning point for the Manhattan Transfer. Part of the change came from a turnover in personnel. Laurel Massé had left the group in 1978, and Cheryl Bentyne had become the newest member of the group. While it’s typical to say that Bentyne replaced Massé, such a statement misses the point: Because the human body is basically the vocalist’s instrument, changing out a singer in a small vocal group is much more involved than swapping trumpeters in a big band. Bentyne and Massé had completely different sounds and styles, and when Bentyne came in, the entire sound of the group changed. Each member of the Transfer had to adjust their sounds to create a new and different blend, and it is highly probable that existing arrangements were re-written to suit the new collection of voices.

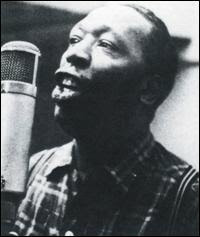

Another important factor came from a man who didn’t sing a note on the album and wasn’t alive to hear the final recording: Eddie Jefferson. Jefferson was known as “the Godfather of Vocalese”, and he claimed to have invented the style in 1939 (There were actually a couple of lyricized versions of Bix Beiderbecke’s “Singin’ the Blues” that preceded Jefferson’s efforts, but it is doubtful that Jefferson heard them before creating his own pieces). In partnership with the brilliant alto saxophonist Richie Cole, Jefferson achieved his greatest popular success in the mid to late 1970s. On April 25, 1979, Jefferson, Cole, the Transfer and Tom Waits performed together on Cole’s album, “Hollywood Madness”. Just two weeks later, Jefferson was murdered outside a Detroit nightclub. According to the Transfer’s website, the group had asked Jefferson to write lyrics for Joe Zawinul’s “Birdland”, but Jefferson was killed before completing the words. Jon Hendricks took the commission after Jefferson’s death, contributing some of his finest lyrics to date.

As a whole, “Extensions” is a very entertaining album. Most of the electronic pieces appeared on the first side, including “Wacky Dust”, a remake of an Ella Fitzgerald/Chick Webb song about cocaine, with Greg Mathieson and Michael Boddicker creating a virtual big band on synthesizers; “Nothin’ You Can Do About It”, a powerful pop song about the inevitability of love; and “Coo Coo U”, a cover of a very strange Kingston Trio song that’s even stranger in the Transfer’s version, with the voices unrecognizable through vocoders over a hyper-energized synthesizer background. Two songs from the second side, the delicious sci-fi parody “Twilight Tone” and Alan Paul’s buoyant doo-wop feature, “Trickle Trickle” were hits for the group, both charting on Billboard’s Hot 100. However, from a jazz viewpoint, the enduring legacy of “Extensions” stems from four tracks: “Birdland”, “Shaker Song”, “Body and Soul” and “Foreign Affair”.

“Birdland” made the biggest impact. As the opening track, it established the synthesizer-heavy sound of the album, but it also established its jazz credentials through references to Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Count Basie and Cannonball Adderley. The composition “Birdland” was not written for a big band or a bebop combo, but for the fusion band, Weather Report. The tune’s intricate structure and electronic-based sound called for a new style of vocalese lyrics. Hendricks created a multi-level story unique among his creations, and the Transfer’s stunning arrangement and performance perfectly realized the concept. By 1979, the famous New York jazz club Birdland, had only been closed for about 15 years; Hendricks takes it far into the future: 5000 light years from Birdland, and I’m still feeling the spirit. Janis Siegel’s sharply pointed delivery makes her voice sound otherworldly, and the ensemble responses sound slightly robotic. With a low sigh from Tim Hauser and Alan Paul, the memories become more personal: In the middle of that hub, I remember one jazz club, where we went to pat feet, down on 52nd Street. Everybody heard that word that they named it after Bird. Where the rhythm swooped and swirled, the jazz corner of the world. After a short spoken interlude, the tune’s famous shout chorus appears, and we are fully immersed in the memories of the great nightspot. There are still occasional remnants of the future interspersed with the memory, as in the cryptic hipster lingo of Hauser’s rendition of Zawinul’s low-register keyboard solo, or in the descending backgrounds behind Siegel’s version of Wayne Shorter’s tenor sax solo. But after Richie Cole’s brief alto solo, all attention goes to the steadily building arrangement. The shout chorus makes a joyous return closing with Siegel singing another Zawinul synth solo over the final fade.

“Shaker Song” also came from the world of jazz/rock fusion, specifically the group Spyro Gyra. While this delightful song is not nearly as adventurous as “Birdland”, the vocal version probably gave this song a much longer shelf life than it ever would have had as an instrumental. Lyricists Allee Willis and David Lasley turn the song into a tale about a lover’s quarrel, breakup and reconciliation. Lifted by an exquisite pun on the title line He can’t shake her, and including fine imagery like He finds a joint that’s jive/Guys are spinning girls like 45s, the song never gets as heavy-handed as its subject matter might lead. Siegel again takes the lead vocal, which is set in the third person, so we’re never quite sure if the experience is hers or just one that she recognizes. In either case, Siegel’s tone has an undercurrent of understanding and forgiveness that makes it clear that th e two lovers will eventually reunite. Overall, the performance has an infectious Latin groove and an outstanding solo by Cole.

e two lovers will eventually reunite. Overall, the performance has an infectious Latin groove and an outstanding solo by Cole.

Eddie Jefferson (left) first recorded his vocalese setting of Coleman Hawkins’ “Body and Soul” in 1959. He made the song a tribute to Hawkins’ life and work, and while the biography wasn’t always right (Hawkins was never as hungry for audience approval as Jefferson contended), it was a heartfelt salute from one artist to another. After Jefferson’s murder, Phil Mattson created a four-part arrangement of Jefferson’s “Body and Soul” for the Transfer, adapting the second chorus to celebrate Jefferson’s life and accomplishments. Accompanied by the stellar trio of Bill Mays (piano), Chuck Domanico (bass) and Ralph Humphrey (drums), the Transfer sings some of their most finely nuanced ensemble singing on this track. Mattson’s arrangement has become the standard version for this tribute.

The album’s closing track, Tom Waits’ “Foreign Affair”, was arranged by Gene Puerling. Puerling’s regular group, the Singers Unlimited was a studio-only group, which allowed him to multi-track up to 27 vocal parts to create his unique voicings. For the Transfer, he retained his signature sound with just four background voices and two overdubbed lead vocals (He would do himself one better on his next arrangement for the Transfer, the four-part—with no overdubs—“A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square”. By the time that track was released, on the 1981 LP, “Mecca for Moderns”, the Singers Unlimited had disbanded.) Waits’ convoluted texts can be difficult to sing, but Hauser’s understated solo brings out the utter charm of the words. Bentyne gets a brief solo in the second chorus, and she delivers an unforgettable reading that communicates the lyric’s depth and feeling.

After winning two Grammys for “Birdland”, the Manhattan Transfer continued to explore jazz and vocalese through several albums (with Paul and Bentyne taking increased roles). Although they have continued to record jazz for the past 30 years, their single finest work in the genre may be their 1985 album, “Vocalese”, which featured the words and vocals of Jon Hendricks. The 1980s were an important time for vocal music, with the debuts of highly influential (and still active) artists like Bobby McFerrin, Take 6, New York Voices and The Real Group. UNC continues to be an important center for vocal jazz activity. Although the Vocal Jazz Festival no longer exists on its own, college and high school groups still play an important role at the annual Greeley Jazz Festival each April. After years of feuding between the opera and jazz departments, UNC will offer a vocal jazz performance degree in 2015. Meanwhile, the Manhattan Transfer continues to tour, albeit without its founder Tim Hauser, who passed away in the autumn of 2014. The fine vocalist Trist Curless has taken Hauser’s spot and once again, the Transfer has adapted its sound and blend to accommodate a new and talented singer. Will we see a new artistic direction with this personnel change?