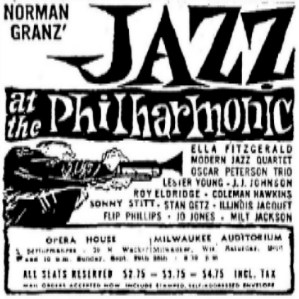

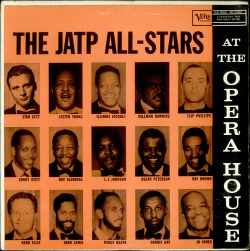

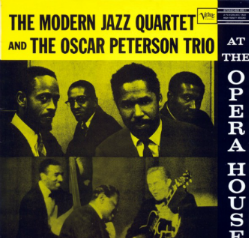

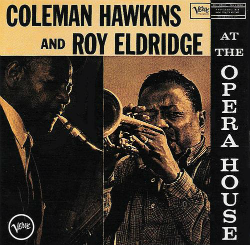

In 1957, Norman Granz (right) presented the 18th edition of Jazz at the Philharmonic, which was the troupe’s last annual North American tour. Although Granz booked a stunning collection of jazz talent, including Ella Fitzgerald, the Oscar Peterson Trio, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Stan Getz, J.J. Johnson, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, Lester Young, Illinois Jacquet, Sonny Stitt, Flip Phillips, and Jo Jones, the audiences were noticeably smaller than in previous years. Granz knew he could make up for disappointing box office receipts with live recordings of the concerts. Significantly, the JATP moniker was dropped on these albums (except for the JATP All-Stars) in favor of the umbrella title, “At the Opera House”. Granz recorded concerts at New York’s Carnegie Hall on September 14, Chicago’s Civic Opera House on September 29, and Los Angeles’ Shrine Auditorium on October 9. Five separate albums were released in both mono and stereo editions.

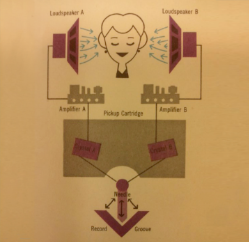

To understand the significance of the mono and stereo versions of the “Opera House” recordings, we must backtrack a little bit. In the autumn of 1957, there was no such thing as a stereo LP. Stereo wasn’t really new: it was invented in the 1930s, but the idea was shelved due to the Great Depression. With a 1954 recording of the Boston Symphony performing Berlioz’ “Damnation of Faust”, RCA entered the home stereo market, offering their recordings on commercially duplicated reel-to-reel tapes. At first, having a home stereo system was strictly for hobbyists with lots of disposable income (one source says that creating a home stereo could cost as much as a new car). But with the stereo LP due for mass production in 1958, RCA and other manufacturers tried to bring the price of home stereo down to affordable levels. Still, stereo was not a surefire hit: to play the new LPs,  consumers had to buy a new turntable (or retrofit their mono one) and add both a second amplifier and a second speaker. Even Norman Granz was unconvinced, saying that he preferred mono.

consumers had to buy a new turntable (or retrofit their mono one) and add both a second amplifier and a second speaker. Even Norman Granz was unconvinced, saying that he preferred mono.

After RCA’s initial plunge, other record companies jumped on the bandwagon by recording their new albums in stereo. (Some of these companies—including Granz’s Verve—did not have facilities for issuing tapes, so the stereo masters remained in the vaults until stereo LPs could be made.) While the record companies showed great confidence in stereo sound, the technology was not always up to the task. Whenever a stereo tape recorder malfunctioned during a session, the musicians would have to wait for the machine to be repaired and then record a new take for the stereo LP. The stereo editions of Bill Evans’ “Portrait in Jazz”, Sonny Clark’s “Sonny’s Crib” and Gerry Mulligan’s “Songbook” contain at least one track with a different take than the mono edition. When a delay interrupted the recording of the album “Indigos”, Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn rewrote portions of their big band arrangements before recording the stereo versions!

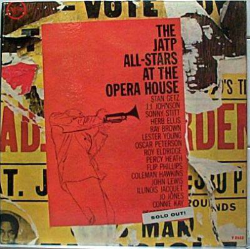

However, all of the above discrepancies are minor when compared to the “Opera House” albums. Those who bought the stereo LPs of the Ella Fitzgerald, Stan Getz/J.J. Johnson, and Coleman Hawkins/Roy Eldridge albums got exactly what was advertised: concert recordings made at the Chicago Opera House. However, the mono editions of those albums contained music recorded at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles! (Both the Fitzgerald and Getz/Johnson mono discs were entirely from the Shrine; the Hawkins/Eldridge had LA on the first s ide and Chicago on the second). Both the mono and stereo versions of the Peterson/MJQ disc contained identical performances from the Chicago concerts, and the album by the JATP All-Stars (containing the evening’s jam sessions) was only issued in mono. And as it will become increasingly clear, the record companies did not acknowledge these discrepancies until many years later.

ide and Chicago on the second). Both the mono and stereo versions of the Peterson/MJQ disc contained identical performances from the Chicago concerts, and the album by the JATP All-Stars (containing the evening’s jam sessions) was only issued in mono. And as it will become increasingly clear, the record companies did not acknowledge these discrepancies until many years later.

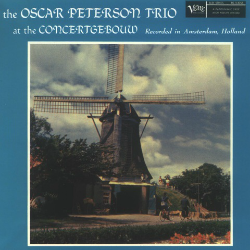

Confused yet? Wait—it gets worse. For years, historians disagreed about the actual dates of the concerts, and about which concert was recorded in stereo. The advertisement (above right) establishes the date of the Chicago concert as September 29, 1957. The LA concert was thought to be held on October 7, but recent research by Granz biographer Tad Hershorn shows that the troupe was in San Jose that night. A contemporary ad confirms that the Shrine performance took place on October 9. Researchers with access to the master tapes have confirmed that all of the stereo recordings were made in Chicago, and all of the mono recordings are from LA. But were they? There are two Oscar Peterson sets said to have been recorded at the Shrine (even though there was only one concert that night, and an LA Times concert review makes no mention of a second Peterson set). Regardless of where they were recorded, the two mono sets by Peterson’s group do not include any selections from the stereo Chicago recordings. Even if they were recorded during the 1957 JATP tour, there was no way to issue these sets under the “Opera House” banner. So naturally, Granz issued the recording as “Oscar Peterson Trio at the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam” (even though all evidence shows that these sets were not recorded in The Netherlands). The source of the extra Peterson sets remains a mystery.

And what about that mono-only “JATP All-Stars” album?  The Granz introduction on the disc, jazz historian Bob Porter‘s research, and the music itself make it clear that this disc is from the mono LA tapes. The earliest issues of the mono LP included a different version of the ballad medley and a stand-alone drum solo by Jo Jones, instead of the 15-minute Hawkins-led jam on “Stuffy” used on later editions. Discographies also list a stereo edition of this album (Verve MGVS-6029) issued by MGM after they bought Verve from Granz. This album is extremely rare, and I have been unable to find a copy from collectors, libraries, online shops, or physical record stores. One collector assured me that his copy was in true stereo, but when I asked him to copy the disc, he said that he couldn’t do so because he had sold the record several years before! If the collector’s memory is correct, the LP may have contained the flawed tapes from Chicago. However, if the album was just an electronically reprocessed stereo edition of the mono LP (my guess), then it’s just the LA concert in inferior sound. Leaving out

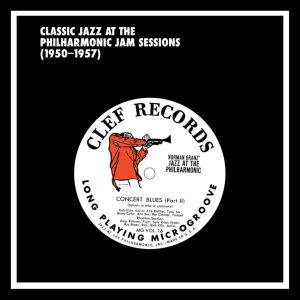

The Granz introduction on the disc, jazz historian Bob Porter‘s research, and the music itself make it clear that this disc is from the mono LA tapes. The earliest issues of the mono LP included a different version of the ballad medley and a stand-alone drum solo by Jo Jones, instead of the 15-minute Hawkins-led jam on “Stuffy” used on later editions. Discographies also list a stereo edition of this album (Verve MGVS-6029) issued by MGM after they bought Verve from Granz. This album is extremely rare, and I have been unable to find a copy from collectors, libraries, online shops, or physical record stores. One collector assured me that his copy was in true stereo, but when I asked him to copy the disc, he said that he couldn’t do so because he had sold the record several years before! If the collector’s memory is correct, the LP may have contained the flawed tapes from Chicago. However, if the album was just an electronically reprocessed stereo edition of the mono LP (my guess), then it’s just the LA concert in inferior sound. Leaving out  the possibility of an unintended issue of the stereo concert, the first complete edition of the Chicago jam sessions appears on Mosaic’s box set “Classic Jazz at the Philharmonic Jam Sessions” (Prior to the 2023 Mosiac release, the only released portion of the Chicago jam sessions released was a section of the ballad medley included on “Carnegie Blues”, a Lester Young JATP compilation LP produced by Porter.)

the possibility of an unintended issue of the stereo concert, the first complete edition of the Chicago jam sessions appears on Mosaic’s box set “Classic Jazz at the Philharmonic Jam Sessions” (Prior to the 2023 Mosiac release, the only released portion of the Chicago jam sessions released was a section of the ballad medley included on “Carnegie Blues”, a Lester Young JATP compilation LP produced by Porter.)

When faced with this discographical nightmare, Tom Lord’s online “Jazz Discography” advised its readers, “Take your pick; the music’s great”. The current CD reissues combine the mono and stereo editions of these albums, making it easy to compare the two concerts. Opinions vary on whether the mono or stereo album is better, but in truth, each concert has its triumphs and misfires. I offer my opinions with the full understanding that others will take the exact opposite view!

The ticket prices for the JATP concerts ranged from $2.75 to $4.75, and Granz gave the audiences their money’s worth. Each show ran in excess of three hours and included six sets of music. The program started with the JATP All-Stars jam session, followed by the Modern Jazz Quartet, and the Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge quintet. The second half featured the Oscar Peterson Trio, the Stan Getz/J.J. Johnson quintet, and Ella Fitzgerald. The program concluded with another jam, as Fitzgerald brought up all of the horns for “Stompin’ at the Savoy” (and at least in LA) “Oh, Lady Be Good”. Granz was willing to let the shows run long when recording, but there is no reason to believe that all of the music on the LPs came from single concerts, especially if he could choose from performances from the early and late shows. Only a full examination of the master tapes will tell what unissued gems remain. For now, we can only discuss the substantial amount of music already released.

In the liner notes to the “JATP All-Stars” album, Granz writes For years, I’ve loved slow blues, as have most musicians, but there never seemed to be a spot in which to fit them on a normal jazz concert. This time we used the slow blues not only as a composition in itself but as an introductory device…. The concerts opened with Peterson alone on stage (apparently without a spoken introduction) playing a pair of highly decorated blues choruses, followed in turn by Ray Brown and Herb Ellis. After Ellis, Jo Jones came on to complete the rhythm section, as Lester Young began his solo. Young’s conception avoided any unnecessary notes, and the purity of his choruses compare favorably to the busy solos that preceded it. Young’s solo set the pace for the rest of the number, with Flip Phillips employing more restraint than he usually did at JATP, Sonny Stitt adding a soulful alto improvisation that included a pair of quotes from “Parker’s Mood”, and Illinois Jacquet closing thin gs off with a preaching chorus. The Chicago version follows the same pattern as the LA version described above, although the mood in Chicago is noticeably mellower than in LA. [An alternate version of “The Slow Blues” was issued on the bootleg Hall of Fame label. Instead of giving the soloists two choruses each to improvise, the Hall of Fame version has each musician playing one chorus. It doesn’t work too well—the soloists barely get started when the audience acknowledges the next soloist’s entrance—so was this version an early run-through, recorded at Carnegie Hall?]

gs off with a preaching chorus. The Chicago version follows the same pattern as the LA version described above, although the mood in Chicago is noticeably mellower than in LA. [An alternate version of “The Slow Blues” was issued on the bootleg Hall of Fame label. Instead of giving the soloists two choruses each to improvise, the Hall of Fame version has each musician playing one chorus. It doesn’t work too well—the soloists barely get started when the audience acknowledges the next soloist’s entrance—so was this version an early run-through, recorded at Carnegie Hall?]

After Granz introduces the musicians, the group launches into the fast-paced “Merry-Go-Round”. This themeless variant on “I Got Rhythm” opens with a powerful solo by Phillips that builds with help from Jones and the horns (Jones’ bass drum bombs are distorted on the original Chicago tape; was this the reason why the stereo LP was withheld?) Young’s solo shows that he could still float his lines over the ground beat and play engaging rhythmic figures. Stitt switched to tenor for this tune, and his strutting, aggressive choruses display why he was such a terror at jam sessions. Jacquet again takes the final slot. He growls a lot throughout his solo, but despite the surging energy from the rhythm section and the background riffs, he stays out of the altissimo register until the final chords.

Discographies tell us that the Chicago ballad medley opened with Stitt’s version of “This is Always”, but this performance is missing from the recording, either because it wasn’t performed at the Opera House, or because Granz cut it from the tape. The issued excerpt opens with Jacquet playing a fine, restrained version of his original composition, “Robbins’ Nest”. Young follows with a tender rendition of “Polka Dots and Moonbeams”. While the tremor in Young’s sound probably wasn’t intentional, it certainly helps portray the story of the lyrics. Phillips finishes off the proceedings with a relaxed chorus of “Can’t We Be Friends”. The version of the ballad medley on the early versions of the “JATP All-Stars” LP includes “This is Always” (with Stitt playing in a passionate bop style) followed by alternative versions of the other three ballads. I cannot agree with Porter’s assertion that this mono version (almost certainly from the LA concerts) is inferior. The tenor men take greater chances in their solos, and the tempos seem better tailored to the soloists. Jo Jones’ drum solo is a true crowd-pleaser, featuring many of his signature solo devices.

To close the jam session segment, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, Stan Getz, and J.J. Johnson joined the Peterson quartet (with Brown still on bass in Chicago, but Percy Heath likely replacing him in LA) for a jam session on “Stuffy”. The LA version was released on the second side of the common “JATP All-Stars” LP. In that version, the crowd can be heard cheering and clapping throughout Eldridge’s dynamic solo, and while they calm down during Hawkins’ choruses, they clearly appreciate the renewed energy of the rhythm section. And while “Stuffy” contains his longest solo of the concert, Hawkins never seems to run out of ideas. Johnson is much more restrained than Hawkins or Eldridge, but his concentrated solo is particularly well-modulated, especially when playing on top of the background horn riffs. (There’s a great moment where Johnson and the other horns volley the opening phrase of “My Blue Heaven” back and forth!). Getz starts off his solo in cool style, but Jones’ forceful accents push the saxophonist into more intensity. Jones plays several powerful breaks against the horns in the penultimate chorus. In Chicago, the performance is five minutes shorter, and far less rowdy, with the solo order changed to Getz, Hawkins, Johnson, and Eldridge. That version had its first release on the Mosaic JATP box set.

No one seems to know how Norman Granz was able to record the Modern Jazz Quartet’s performances from the Chicago concert, as the group was under contract to Atlantic Records at the time. It’s possible that Atlantic heard about the Chicago recording and instructed Granz not to record the group in LA (but that doesn’t explain how he was able to issue the Chicago recording without printed acknowledgment that “the MJQ appears courtesy of Atlantic Records”!) What is clear is that Atlantic’s engineers had a much better sense of how to record this delicate group than Granz’s engineers. The Opera House recording sounds quite distant, without the presence and richness of the MJQ’s Atlantic recordings. Nevertheless, the group plays a fine abbreviated set starting with “D & E Blues”, which opens with staggered entrances by Connie Kay, Percy Heath, John Lewis, and Milt Jackson, and quickly falls into an irresistible groove. Jackson’s restrained but soulful solo is backed with a combination of jabbing chords and melodic ideas from Lewis, who follows with a pithy solo that develops a handful of simple blues phrases. A sinewy take on “Now’s the Time” follows. Lewis steals the show here, with intriguing comping behind Jackson, and a remarkable solo based on Charlie Parker’s melody. In contrast, the medium tempo on “Round Midnight” seems too fast for this ballad (at times, it feels almost march-like!). The liveliest track of the MJQ’s set, “I’ll Remember April”, features a thrilling dialogue between Jackson and Lewis, and delightful swing from Heath’s strong bass and Kay’s dancing cymbals. This final track was not issued on the original LP but was eventually released (with the rest of the session) on Verve’s “Compact Jazz” compilation.

No one seems to know how Norman Granz was able to record the Modern Jazz Quartet’s performances from the Chicago concert, as the group was under contract to Atlantic Records at the time. It’s possible that Atlantic heard about the Chicago recording and instructed Granz not to record the group in LA (but that doesn’t explain how he was able to issue the Chicago recording without printed acknowledgment that “the MJQ appears courtesy of Atlantic Records”!) What is clear is that Atlantic’s engineers had a much better sense of how to record this delicate group than Granz’s engineers. The Opera House recording sounds quite distant, without the presence and richness of the MJQ’s Atlantic recordings. Nevertheless, the group plays a fine abbreviated set starting with “D & E Blues”, which opens with staggered entrances by Connie Kay, Percy Heath, John Lewis, and Milt Jackson, and quickly falls into an irresistible groove. Jackson’s restrained but soulful solo is backed with a combination of jabbing chords and melodic ideas from Lewis, who follows with a pithy solo that develops a handful of simple blues phrases. A sinewy take on “Now’s the Time” follows. Lewis steals the show here, with intriguing comping behind Jackson, and a remarkable solo based on Charlie Parker’s melody. In contrast, the medium tempo on “Round Midnight” seems too fast for this ballad (at times, it feels almost march-like!). The liveliest track of the MJQ’s set, “I’ll Remember April”, features a thrilling dialogue between Jackson and Lewis, and delightful swing from Heath’s strong bass and Kay’s dancing cymbals. This final track was not issued on the original LP but was eventually released (with the rest of the session) on Verve’s “Compact Jazz” compilation.

The MJQ (sans Jackson) remained onstage to back Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge. As Kevin Whitehead writes in the liner notes for the CD reissue, some JATP fans considered Hawkins and Eldridge to be “living dinosaurs”. Certainly, these men had been part of the jazz scene for decades, but they were also highly aware of the latest jazz styles, and they were able to play in their own styles alongside the younger generation. Lewis, Heath, and Kay pounce like cats behind the horns on the stereo “Bean Stalkin’”, and Eldridge’s cup-muted solo is delightful against Kay’s brushes and cymbals. Hawkins digs in for his choruses, smoothing out his jagged dotted-eighth/sixteenth note patterns to better mesh with the rhythm section. The ensuing four-bar exchanges contrast Eldridge’s fiery melodies with Hawkins’ arpeggiated style. Eldridge removes the mute for a ballad version of “The Nearness of You”. While Eldridge includes a few of his signature rasps, he plays most of the solo with a warm open tone. Hawkins is back for a romantic “Time on my Hands” with Lewis basing his accompaniment on the song’s opening phrase. The first side closes with “The Walker”, a Hawkins-Eldridge original based on “Stompin’ at the Savoy”. Eldridge spits fire from his trumpet, but it sounds like his lip gives him trouble, as he misses a few notes in his solo. Hawkins seems much more relaxed in his first chorus, but turns up the heat in the second with a few growls and an oblique reference to “Th anks for the Memory”. The mono version of “Bean Stalkin’” is noticeably faster and that makes the horn solos punchier and less diverse than the stereo. Eldridge changes his ballad feature to “I Can’t Get Started” and Eldridge’s version is a very personal statement. Hawkins sticks with “Time on My Hands”, but the mono rendition has a different contour than the stereo. Rather than just creating a subdued reading with one or two dramatic leaps into the upper register, the LA version is a series of peaks and valleys with a better melodic feel than in Chicago. Eldridge is spectacular on the mono version of “The Walker”, with none of the technical problems from the stereo version. Hawkins aggressively pushes the rhythm this time, but Kay’s rock-ish backbeats are less pronounced in this version.

anks for the Memory”. The mono version of “Bean Stalkin’” is noticeably faster and that makes the horn solos punchier and less diverse than the stereo. Eldridge changes his ballad feature to “I Can’t Get Started” and Eldridge’s version is a very personal statement. Hawkins sticks with “Time on My Hands”, but the mono rendition has a different contour than the stereo. Rather than just creating a subdued reading with one or two dramatic leaps into the upper register, the LA version is a series of peaks and valleys with a better melodic feel than in Chicago. Eldridge is spectacular on the mono version of “The Walker”, with none of the technical problems from the stereo version. Hawkins aggressively pushes the rhythm this time, but Kay’s rock-ish backbeats are less pronounced in this version.

The second side of the mono and stereo Hawkins/Eldridge LPs both contained music from Chicago. The format mirrored the first side with ensemble pieces bookending two ballads. It is said that Eldridge invented the term “strolling” for improvising with only bass and drums in support. He was surely a master at the technique and he sounds wonderful against Heath’s solid bass and Kay’s brushes on “Tea for Two”. Eldridge vocally encourages Hawkins as the saxophonist creates a fascinating set of rhythmic constructions. Eldridge’s version of “Blue Moon” is relaxed and dreamy, matching Lewis’ understated comping. Hawkins tries to undo the damage that Spike Jones did to “Cocktails for Two”, by concentrating on the chords rather than the melody. At just over two minutes, it seems that Hawkins could say much more on this song, but Granz was probably watching the clock from the wings. “Kerry”, a contrafact on “Sweet Georgia Brown” closes the set with more energized Eldridge and propulsive Hawkins solo.

The three Oscar Peterson trio sets have been collected on single-CD reissues. The Verve reissue uses the original (but misleading) title, “At the Concertgebouw”, but the unauthorized foreign issue is titled “Live at the Opera House and the Shrine Auditorium”. Both reissues correctly state that the music comes from the JATP tour, but they add to the confusion by marking the long mono set as from Chicago and the shorter stereo set from LA! Each side of the Concertgebouw LP contained one of the LA sets, but we may never know which one came first, as a fadeout can be heard following Granz’s introduction of the group on the second side. Taking the music in the disc’s playing order, the first set opens with a tight and speedy version of “Lady is a Tramp”. Peterson gobbles up notes at a ridiculous pace while Ellis and Brown swing mightily behind. Ellis tries to match Peterson’s speed, but at one point his fingers don’t cooperate! Peterson returns for another dazzling solo which includes an unaccompanied spot where he fills in the gaps with his tapping foot and by singing along with his piano lines. “We’ll Be Together Again” offers a brief respite from the fireworks, with fine dialogues between Peterson and Ellis. The longest piece of the three sets is “Bluesology” (mislabeled as “Bags’ Groove” on the original LP). The trio creates a fine loping groove with Brown playing a modified two-beat, and Ellis simulating a conga drum on his guitar. Peterson plays a pair of well constructed solos, with the first including a fine crescendo as the statement builds to its climax. Ellis and Brown also play superb solos, and the audience clearly enjoys what they hear. “Budo” (aka “Hallucinations”) was part of Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool” album, but like the Jets in “West Side Story”, the Peterson trio seems ready to burst the cool demeanor at any moment. The tempo is absurdly fast (but held steady by the redoubtable Brown). Both Ellis and Peterson start their solos softly with plenty of excitement bubbling underneath. The flurries of notes that each plays is truly astounding—and

The three Oscar Peterson trio sets have been collected on single-CD reissues. The Verve reissue uses the original (but misleading) title, “At the Concertgebouw”, but the unauthorized foreign issue is titled “Live at the Opera House and the Shrine Auditorium”. Both reissues correctly state that the music comes from the JATP tour, but they add to the confusion by marking the long mono set as from Chicago and the shorter stereo set from LA! Each side of the Concertgebouw LP contained one of the LA sets, but we may never know which one came first, as a fadeout can be heard following Granz’s introduction of the group on the second side. Taking the music in the disc’s playing order, the first set opens with a tight and speedy version of “Lady is a Tramp”. Peterson gobbles up notes at a ridiculous pace while Ellis and Brown swing mightily behind. Ellis tries to match Peterson’s speed, but at one point his fingers don’t cooperate! Peterson returns for another dazzling solo which includes an unaccompanied spot where he fills in the gaps with his tapping foot and by singing along with his piano lines. “We’ll Be Together Again” offers a brief respite from the fireworks, with fine dialogues between Peterson and Ellis. The longest piece of the three sets is “Bluesology” (mislabeled as “Bags’ Groove” on the original LP). The trio creates a fine loping groove with Brown playing a modified two-beat, and Ellis simulating a conga drum on his guitar. Peterson plays a pair of well constructed solos, with the first including a fine crescendo as the statement builds to its climax. Ellis and Brown also play superb solos, and the audience clearly enjoys what they hear. “Budo” (aka “Hallucinations”) was part of Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool” album, but like the Jets in “West Side Story”, the Peterson trio seems ready to burst the cool demeanor at any moment. The tempo is absurdly fast (but held steady by the redoubtable Brown). Both Ellis and Peterson start their solos softly with plenty of excitement bubbling underneath. The flurries of notes that each plays is truly astounding—and rather overwhelming. The second set is much more relaxed, opening with a medium-tempo “I’ve Got the World on a String”. Peterson still amazes with his sheer velocity, but the interaction with the rest of the group is the best part of this piece (When Ellis and Peterson grab a unison line together, it sounds like Ellis is ready to solo. Actually, it’s just a very effective passage—possibly created on the fly—in the middle of Peterson’s solo). Clifford Brown had passed away 15 months before these concerts, and the Peterson trio performed two of the trumpeter’s finest compositions on the JATP tour. Their arrangement of “Daahoud” retains some of the mysterious flair of Brown’s original recording, and Peterson’s solo is particularly effective in noting the shifts between major and minor modes in the tune’s chord structure. Brown’s tasty bass lines and his walking solo are the highlights of the Benny Carter classic “When Lights are Low”, and “Evrev” concludes the set with Peterson and Ellis egging each other on via their own accompanying styles.

rather overwhelming. The second set is much more relaxed, opening with a medium-tempo “I’ve Got the World on a String”. Peterson still amazes with his sheer velocity, but the interaction with the rest of the group is the best part of this piece (When Ellis and Peterson grab a unison line together, it sounds like Ellis is ready to solo. Actually, it’s just a very effective passage—possibly created on the fly—in the middle of Peterson’s solo). Clifford Brown had passed away 15 months before these concerts, and the Peterson trio performed two of the trumpeter’s finest compositions on the JATP tour. Their arrangement of “Daahoud” retains some of the mysterious flair of Brown’s original recording, and Peterson’s solo is particularly effective in noting the shifts between major and minor modes in the tune’s chord structure. Brown’s tasty bass lines and his walking solo are the highlights of the Benny Carter classic “When Lights are Low”, and “Evrev” concludes the set with Peterson and Ellis egging each other on via their own accompanying styles.

Moving back to the Chicago Opera House, Peterson’s set starts with another of the trio’s complex arrangements, “Should I?” The superb presence of the Chicago recording lets us hear (and feel) the strong sense of swing generated by this group. Peterson reaps the benefits as primary soloist—and what a joyful solo he plays!—but it’s evident that all three musicians were having a great time on the stage that night. The grooving medium swing of “Big Fat Mama” brings out fine solos from all three musicians, and another great piano/guitar dialogue during Ellis’ solo. After a speedy race through “Indiana” comes the other Clifford Brown original, “Joy Spring”. The frilly arrangement removes much of the tune’s charm, and while it sounds like the Peterson trio is trying to honor the composer, I don’t believe that they truly got to the heart of this piece. The set concludes with more lightning-fast playing on Elliot Lawrence’s bop blues line, “Elevation”. While these three sets do not reach the artistic heights of the trio’s wonderful performance at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival the year before, there is little doubt that the Oscar Peterson trio was playing at a very high level on a consistent basis.

“Getz and J.J. at the Opera House” is undoubtedly the best-known of all the “Opera House” albums. Although Getz and Johnson had recorded together at least twice before, the JATP tour was their first opportunity to be the only two horns in the front line. It was an inspired pairing, with the two hornmen spurring each other while the Oscar Peterson trio (with Connie Kay on drums) booted them along. With the exception of “Crazy Rhythm” (a favorite Getz vehicle) and the two ballads, neither Getz nor Johnson had recorded any of the concert repertoire before. The result was one of the most exciting live jazz albums ever made, with the stereo version just edging out the mono (although those who bought the mono LP were probably very happy with the music on that disc). On the stereo (Chicago) version of “Billie’s Bounce”, Getz plays one great idea after another, but his solo holds together better on the mono (LA) version. Johnson has no such problems; his training as a composer comes out in the way he links and develops his improvised ideas. Although it’s not terribly obvious, there’s a little confusion in the chase choruses on the stereo take: Johnson plays behind Getz’s opening solo, and when Johnson takes the spotlight, Getz returns the favor. Somehow, Johnson must have thought that Getz was starting the chase choruses early. That wasn’t the case, because when Johnson stops playing, Getz starts the actual chase. The form was clarified by the time they played the LA concert, and as a result, that performance is about 2 minutes shorter. Bob Porter aptly described the tempo  of the stereo “My Funny Valentine” as a medium walk. It’s a great pace for this tune, and Getz plays wonderful behind-the-beat phrases that were obviously inspired by Lester Young (who could have been in the wings listening). Getz’s solo has an abrupt, declamatory phrase that pops up about the same place every chorus (it also turns up on the mono take), but the overall feeling is of wistfulness and longing. Johnson picks up on Getz’s last line as he launches into a sprightly invention of his own, with delightful triplet figures and a recurring two-note skipping motive. The mono version is a little faster, and it bounces more than it walks. Heath makes a great entrance in the introduction, and the tempo seems to make the whole piece light-hearted. The solos take a different approach but are still well-conceived.

of the stereo “My Funny Valentine” as a medium walk. It’s a great pace for this tune, and Getz plays wonderful behind-the-beat phrases that were obviously inspired by Lester Young (who could have been in the wings listening). Getz’s solo has an abrupt, declamatory phrase that pops up about the same place every chorus (it also turns up on the mono take), but the overall feeling is of wistfulness and longing. Johnson picks up on Getz’s last line as he launches into a sprightly invention of his own, with delightful triplet figures and a recurring two-note skipping motive. The mono version is a little faster, and it bounces more than it walks. Heath makes a great entrance in the introduction, and the tempo seems to make the whole piece light-hearted. The solos take a different approach but are still well-conceived.

Tempo becomes a real nemesis as the mono concert progresses. While the stereo version of “Crazy Rhythm” is an overwhelming combination of invention and swing, the mono version is so fast that the horn men seem to be hanging on for dear life! The problem gets worse on the closing “Blues in the Closet”. The racehorse pace seems to come out of nowhere (Peterson’s introduction sounds like it’s in a completely different—and saner—tempo) and both Getz and Johnson have a very hard time making any kind of coherent statements at this ridiculously fast tempo. The stereo version is brisk, but it still swings. Johnson’s ballad feature, “Yesterdays” appears only on the mono LP (Porter suggests that Granz may have cut the number in Chicago if the concert was running long). Johnson’s performance is exemplary, but the repeating ABAB pattern of the song makes this version seem a little monotonous. However, Getz’s ballad ranks as one of his finest. On the mono version of “It Never Entered My Mind”, he sticks to the melody and brings out the beauty of Richard Rodgers’ melody; on the stereo, he creates a series of delicate variations that enhance both the music and the unheard lyric. As a measure of the high esteem earned by this album, Getz and Johnson were invited to recreate the concert as part of the 1988 Chicago Jazz Festival. A recording of that performance has been issued in Europe, and the track listing shows that Getz and Johnson revisited four of the six songs from their JATP set.

Ella Fitzgerald had been one of the stars of Jazz at the Philharmonic for years, even before Norman Granz became her personal manager. Fitzgerald’s status as a jazz singer grew immeasurably through her JATP appearances, and JATP typically drew larger audiences when Fitzgerald was part of the show. Ironically, Fitzgerald’s performance fees (which had grown considerably under Granz’s guidance) became one of the factors for Granz’s decision to stop the annual JATP tours. The recorded evidence shows that Fitzgerald was worth every penny. When she started recording for Verve in 1956, Fitzgerald entered an artistic peak equaled by few other jazz artists. No matter if she was recording with a full orchestra or a small combo (either live or in the studio), Fitzgerald could seemingly do no wrong. Even when fluffin g a lyric, as on “Them There Eyes” (which only appears on the stereo “Opera House” album), Fitzgerald makes the performance a success through her glowing personality and by laughing at her own mistakes. For her JATP program, Fitzgerald selected music from her nightclub sets. With the backgrounds basically the same (played by the Peterson trio, with Jo Jones now on drums), Fitzgerald let her musical imagination run wild, adding melodic variations and rhythmic emphasis wherever she wished. She sang the same basic set in Chicago and LA, and it is fascinating to listen to the two versions of each song back-to-back: one can hear Fitzgerald adapt phrases that she had left behind before, or improvise elaborate new melodies to enhance the original tunes. The two versions of “These Foolish Things” are particularly enlightening. At each concert, Fitzgerald sang unique variations on this song, both equally fascinating and with only one variation in common to both. Some of her note choices are jaw-droppers, demonstrating that she knew bop harmony as well as the horn players. Yet she makes the whole thing sound effortless, and she never lets the variations disturb the mood of the song.

g a lyric, as on “Them There Eyes” (which only appears on the stereo “Opera House” album), Fitzgerald makes the performance a success through her glowing personality and by laughing at her own mistakes. For her JATP program, Fitzgerald selected music from her nightclub sets. With the backgrounds basically the same (played by the Peterson trio, with Jo Jones now on drums), Fitzgerald let her musical imagination run wild, adding melodic variations and rhythmic emphasis wherever she wished. She sang the same basic set in Chicago and LA, and it is fascinating to listen to the two versions of each song back-to-back: one can hear Fitzgerald adapt phrases that she had left behind before, or improvise elaborate new melodies to enhance the original tunes. The two versions of “These Foolish Things” are particularly enlightening. At each concert, Fitzgerald sang unique variations on this song, both equally fascinating and with only one variation in common to both. Some of her note choices are jaw-droppers, demonstrating that she knew bop harmony as well as the horn players. Yet she makes the whole thing sound effortless, and she never lets the variations disturb the mood of the song.

Except for a solo break in “Goody, Goody”, Fitzgerald saves her scat for the final jam session. The vehicle is “Stompin’ at the Savoy”, a song long associated with her first boss, Chick Webb. Fitzgerald takes the first chorus at a relaxed pace before jumping to a medium-fast tempo for her wordless solo. She alternates between scat and lyrics for the remainder of the performance, improvising soaring lines over the riffing horn section. While the Chicago version is exciting and well-played, it pales when compared to the LA recording. Fitzgerald builds the intensity better in the latter version, and she keeps calling for additional choruses, which gets the audience excited. The drumming on the LA recording is much more explosive and propulsive than on the Chicago version. My guess is that Connie Kay played this set at the Chicago concert, replaced by Jo Jones in LA. At the conclusion of the “Savoy” jam, the cheering audience demands an encore, and Fitzgerald delivers with a version of “Oh, Lady Be Good”. Fitzgerald avoids singing any portions of her classic 1947 Decca scat solo, instead creating fresh improvisations liberally spiced with some of her favorite ideas (You wanna blow now…We gotta go now). Phil Schaap claimed that Jones replaced Kay on this number only, but to my ears, it sounds like the same drummer on “Savoy” and “Lady”.

And if that’s not enough, there may be more unissued music from these concerts remaining in the vaults. When Granz sold the Pablo label to Fantasy Records, he included all of the JATP recordings that were still unreleased by Verve. Tad Hershorn reports that Concord Music Group (who bought Fantasy several years ago) holds the tapes for the unissued Carnegie Hall concerts, as well as several reels with the date October 9, 1957—the date of the Shrine concert! If someone at Concord would examine these tapes, more music from this tour might be deemed suitable for release. It might even solve some of the mysteries connected with these recordings. The saga continues…

Thanks to John Clayton, Pam Garramone, Carla Henebry-Branscome, Tad Hershorn, Barbara Kline, John McDonough, Megan McLean Corso, James Harrod, LaDamion Massey, Dan Morgenstern, Nick Phillips, Bob Porter, Ricky Riccardi, Loren Schoenberg, Ian Shadwick, Eric Smith, Katie Thiroux, Clint Weiler, Dave Weiner, Harry Weinger, and Scott Wenzel.