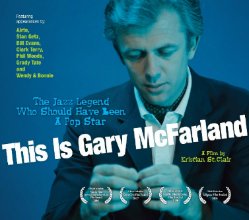

On November 2, 1971, 38-year-old arranger Gary McFarland died after ingesting a drink spiked with methadone. In a career that spanned only a dozen years, McFarland had been praised by jazz critics as the best young big band arranger of his time, and then vilified by many of the same critics when he introduced elements of rock and Brazilian music into his scores. Many of today’s most progressive jazz artists create their sounds by mixing a wide range of musical genres, so it could be said that McFarland was ahead of his time. On his sardonic LP, “America the Beautiful”, McFarland made abrupt jumps between styles and still found a way to make each piece (and the suite) sound like a cohesive whole. His “October Suite” shows a mastery of 20th century composing techniques as he contrasts the jazz piano of Steve Kuhn with string and woodwind ensembles. Unfortunately, most of McFarland’s albums are out-of-print and hard to find. Some of his experiments didn’t work, plagued by dated concepts and amateur vocals. Kristian St. Clair’s documentary “This is Gary McFarland” tries to recover the composer’s lost fame through interviews with McFarland’s family and colleagues, rare film clips, and—on an accompanying CD—a previously unreleased concert by the McFarland Quintet.

On November 2, 1971, 38-year-old arranger Gary McFarland died after ingesting a drink spiked with methadone. In a career that spanned only a dozen years, McFarland had been praised by jazz critics as the best young big band arranger of his time, and then vilified by many of the same critics when he introduced elements of rock and Brazilian music into his scores. Many of today’s most progressive jazz artists create their sounds by mixing a wide range of musical genres, so it could be said that McFarland was ahead of his time. On his sardonic LP, “America the Beautiful”, McFarland made abrupt jumps between styles and still found a way to make each piece (and the suite) sound like a cohesive whole. His “October Suite” shows a mastery of 20th century composing techniques as he contrasts the jazz piano of Steve Kuhn with string and woodwind ensembles. Unfortunately, most of McFarland’s albums are out-of-print and hard to find. Some of his experiments didn’t work, plagued by dated concepts and amateur vocals. Kristian St. Clair’s documentary “This is Gary McFarland” tries to recover the composer’s lost fame through interviews with McFarland’s family and colleagues, rare film clips, and—on an accompanying CD—a previously unreleased concert by the McFarland Quintet.

St. Clair replaces the omniscient voiceover narrator with an animated timeline of McFarland’s life. Family photos and album covers whiz across the screen, sometimes too quickly for the viewer to completely absorb their meaning. Through a combination of vintage audio interviews with McFarland, and filmed interviews with his widow, critic Gene Lees, and musicians Grady Tate, Sy Johnson, Bob Brookmeyer and Marvin Stamm, we get a fairly good picture of McFarland’s overall personality, and his generosity (Johnson’s story about a late night visit from Bill Evans is especially striking). What we don’t get is anyone discussing the elements of McFarland’s music, such as his use of unison lines, his unique method of scoring, and the sudden style changes described above. I’m sure that Johnson and/or Brookmeyer could have easily explained McFarland’s arranging style in a way that non-musicians could understand, but I wonder if they were even asked. Without this sort of explanation, the viewer might wonder why McFarland was any different from the other arrangers of his day, and further, why anyone would want to make a film about him.

The cover of the CD/DVD package adds the tagline, “The jazz legend who should have been a pop star”, and that line truly defines the film. Although segments on “October Suite” and a wild polytonal arrangement of “Straight, No Chaser” are included within the extra features, the main film focuses on McFarland’s infusion of rock and pop styles into his big band scores. Admittedly, this was a major part of McFarland’s style, but leaving the classical influences out of the final cut distorts the breadth of McFarland’s musical horizons. In an article for Downbeat, McFarland described himself as a “anti-purist” but it’s easy to see that McFarland’s classically-themed scores were expanding the boundaries of the Third Stream movement. McFarland learned some of his craft at the Music Inn jazz symposiums, led by the Modern Jazz Quartet’s John Lewis. That crucial information is not mentioned anywhere in the documentary, but we do learn that McFarland was one of the first jazz artists to cover songs by the Beatles.

Two Lennon/McCartney songs (“A Hard Day’s Night” and “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”) are included on the CD, which feature a pair of live quintet dates recorded at The Penthouse in Seattle for radio broadcast. McFarland plays vibes, sharing the front line with flautist/saxophonist Sadao Watanabe (then fresh out of Berklee). The rhythm section is filled with young emerging talent: guitarist Gábor Szábo, bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Joe Cocuzzo. McFarland spices up the arrangements with background riffs, extended codas and intriguing percussion colors. He also proves to be an accomplished improviser (I am less impressed when he scats and whistles). Watanabe plays a lovely flute solo on “Mañha de Carnival” (somehow omitted from the track listing) and Szábo improvises a well-constructed statement over Cocuzzo’s broken time patterns on “I Thought about You”. On an incomplete take of “From Russia with Love”, Gomez plays a brilliant solo that presages his work in the Bill Evans trio. The most fascinating piece on the CD is one marked “unknown Latin number”. It is an up-tempo blues which inspires all of the soloists, and lets Cocuzzo go wild with unpredictable rhythm patterns and plenty of bombs. This piece could have led McFarland into another new direction, yet there is no evidence that he recorded it again—or even titled it!

While the film has a narrow focus, it is compact and well-paced. The interviews are interesting, and the film clips (a television performance with Stan Getz, and home movies of McFarland’s wedding and reception) are in good shape considering their age. Apparently, the documentary has been on the shelf for a few years, so if the DVD generates some public screenings, St.Clair might want to amend the final credits to acknowledge the passing of Lees, Brookmeyer, and McFarland’s widow. If this film catches the attention of Universal Music, that company (which owns most of McFarland’s recordings) should issue a McFarland sampler—perhaps with a few later tracks licensed from McFarland’s Skye label. Although his output was somewhat uneven, McFarland deserves long overdue recognition for his imaginative and far-reaching music.