In 1984, while recuperating from a leg injury, baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams was visited by Gary Carner, who was at the time a City College of New York graduate student researching a thesis on Adams’ life and works. The temporarily incapacitated Adams was happy to relate stories to his student biographer, but plans to publish his memoirs were shelved when Adams was diagnosed with lung cancer. Adams passed away in 1986, and while he did see a version of Carner’s manuscript, it’s doubtful he would have imagined the massive collection of material Carner has released 26 years after the saxophonist’s death. First is an annotated discography “Pepper Adams’ Joy Road” (Scarecrow) which in its 552 pages lists Adams’ entire recorded history, including unissued sessions dating back to 1947, and several filmed appearances. In addition, Carner produced a series of recordings that present all 43 of Adams’ compositions, and commissioned lyrics for seven of the ballads. The recordings have been collected in a digital box set from Motéma, “Joy Road: The Complete Works of Pepper Adams”. A budget-priced sampler is available in CD format, and the album of vocal versions (sung by Alexis Cole) is also available on disc. Supplementing the entire collection is Carner’s massive website, which features audio and video clips, articles, and several excerpts from Carner’s thesis.

In 1984, while recuperating from a leg injury, baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams was visited by Gary Carner, who was at the time a City College of New York graduate student researching a thesis on Adams’ life and works. The temporarily incapacitated Adams was happy to relate stories to his student biographer, but plans to publish his memoirs were shelved when Adams was diagnosed with lung cancer. Adams passed away in 1986, and while he did see a version of Carner’s manuscript, it’s doubtful he would have imagined the massive collection of material Carner has released 26 years after the saxophonist’s death. First is an annotated discography “Pepper Adams’ Joy Road” (Scarecrow) which in its 552 pages lists Adams’ entire recorded history, including unissued sessions dating back to 1947, and several filmed appearances. In addition, Carner produced a series of recordings that present all 43 of Adams’ compositions, and commissioned lyrics for seven of the ballads. The recordings have been collected in a digital box set from Motéma, “Joy Road: The Complete Works of Pepper Adams”. A budget-priced sampler is available in CD format, and the album of vocal versions (sung by Alexis Cole) is also available on disc. Supplementing the entire collection is Carner’s massive website, which features audio and video clips, articles, and several excerpts from Carner’s thesis.

The discography is separated into five sections: “The Early Years” (1947-1958 dates in Detroit, New York and California), “Donald Byrd/Pepper Adams Quintet” (1958-1961), “Journeyman” (1961-1965 sideman recordings), “Thaddeus” (1965-1977, as member of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis big band) and “International Soloist” (1977-1986, his work as a leader). The layout of the record listings is not terribly intuitive, but a brief explanation at the beginning of the book helps to sort things out. Carner’s listings would have been much easier to read if he had placed the complete albums first and then reissues of individual tracks; instead, each track is listed separately with the same album numbers listed numerous times. Additionally, he fusses too much about the specific days of the week when the sessions were recorded. While it was a general rule that Savoy, Prestige and Blue Note had specific days when they preferred to record at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio, the schedule was probably shifted around to accommodate the musician’s schedules. And was it really necessary to refer back to a single—and not very revealing—paragraph about Van Gelder’s studio for every session Adams recorded there? There are copious notes and quotes about the various recordings, but Carner has not organized and sifted the material to get to the true story. For example, referring to a 1956 session with Curtis Fuller and John Coltrane, Carner quotes Fuller as saying that the group had recorded enough material for 2 LPs. However, only one of the tracks was issued on the original label, Transition, and the only three surviving tracks were later issued on Blue Note. Obviously, three tracks are not enough for an album—let alone two—and Fuller must have confused this date with another session. With Fuller still alive and working, Carner should have double-checked the facts, or at the very least mention that there could be unissued titles from the session. As it is, it’s a rather blatant embarrassment for a respected jazz master.

Browsing through the listings provide several surprises. Did you know that Adams toured with the bands of Stan Kenton, Maynard Ferguson, Woody Herman and Lionel Hampton? And that he recorded with Thad Jones and Mel Lewis separately long before he joined their big band? The section on Thad and Mel’s big band is a treasure chest of great anecdotes and historical trivia, and the final section is filled with information on private recordings and videotapes (I was a little disappointed that my first exposure to Adams and the Jones/Lewis band, a 1974 appearance on the PBS series “At The Top” was not listed in complete form. I had an audio tape of the broadcast—long since lost—and I remember it included an extended version of “Us” which featured Adams, plus Neal Hefti’s “Pensive Miss”, and several pieces from the band’s “Potpourri” album, including “Ambiance”, “For the Love of Money”, “All My Yesterdays” and “Living for the City”. Carner says it’s unclear if audio or video still exists. If it does, I’d love to get a copy.)

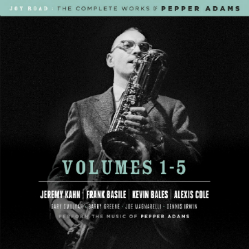

The music for the digital box set was recorded between 2006 and 2011. The groups are led by lesser-known “local” musicians including pianists Jeremy Kahn (from Chicago) and Kevin Bales (Tallahassee), and baritone  saxophonist Frank Basile (New York) but the musical quality is quite high throughout, and several of the sidemen, including saxophonists Gary Smulyan, Pat LaBarbera and Eric Alexander, trombonist John Mosca and bassist Dennis Irwin, are well-known to national jazz audiences. Smulyan, a long-time admirer of Adams, is as brilliant as expected (especially on a rapid-fire bari/drums duet on “Diabolique II” from Volume 4), but the biggest stunner is guitarist Barry Greene, who dominates Volume 2 with jaw-dropping solos. On Volume 3, Basile’s charts for three horns and rhythm offer close replications to Adams’ original recordings. On the other hand, Kahn’s lengthy trio set on Volume 1 only catches fire when tenor saxophonist Eric Schneider joins the group for “Beaubien”. Volume 5, the vocal album, is a mixed bag: Alexis Cole sings these challenging songs with great flair, but the words by Carner’s former college professor Barry Wallenstein are closer to poetry than song lyrics, and they’re not very easy to sing. LaBarbera and Alexander are the main soloists on this volume, but there are no solo order listings or even a designation of which tenor plays on each audio channel.

saxophonist Frank Basile (New York) but the musical quality is quite high throughout, and several of the sidemen, including saxophonists Gary Smulyan, Pat LaBarbera and Eric Alexander, trombonist John Mosca and bassist Dennis Irwin, are well-known to national jazz audiences. Smulyan, a long-time admirer of Adams, is as brilliant as expected (especially on a rapid-fire bari/drums duet on “Diabolique II” from Volume 4), but the biggest stunner is guitarist Barry Greene, who dominates Volume 2 with jaw-dropping solos. On Volume 3, Basile’s charts for three horns and rhythm offer close replications to Adams’ original recordings. On the other hand, Kahn’s lengthy trio set on Volume 1 only catches fire when tenor saxophonist Eric Schneider joins the group for “Beaubien”. Volume 5, the vocal album, is a mixed bag: Alexis Cole sings these challenging songs with great flair, but the words by Carner’s former college professor Barry Wallenstein are closer to poetry than song lyrics, and they’re not very easy to sing. LaBarbera and Alexander are the main soloists on this volume, but there are no solo order listings or even a designation of which tenor plays on each audio channel.

The lack of identifications on Volume 5 brings me to my biggest problem with this collection: there is no biographical sketch included anywhere in this material. Such an essay—which should have appeared in all of these items–would introduce Pepper Adams to new listeners, explain his historical importance and tie together all of the loose ends in the liner notes and discography. I’m sure Carner wrote something of this nature for his thesis, so why isn’t there a revised version here? Carner is doing Adams an invaluable service, but it is ridiculous to jump between a discography, a website and three sets of liner notes to find scraps of important information. Hidden away at the back of the notes for the boxed set are track-by-track listings by Carner about the background of each composition (for the moment, we’ll ignore the fact that there is no table of contents to direct the reader there). Track 38 “Dylan’s Delight” was named for Adams’ stepson. We’re told that Adams married for the first time in 1976. Track 40, “Now In Our Lives” was written in 1982 about Adams’ failing marriage. So what happened? Did they reconcile, separate, divorce? I couldn’t find any information on the website chronology or in the discography.

While this collection is being promoted by a nationwide tour, it is truly an incomplete project. Carner promises a full biography of Adams (and one hopes that it will publish long before Adams’ centenary in 2030!), but shouldn’t the biography have been created first? Again, I must assume that Carner has a version of Adams’ biography within his thesis. And what about the music? Now that Adams’ 43 compositions have been transcribed, arranged and recorded, how about publishing those works in an authoritative edition? Pepper Adams may have been an “underground musician” during his lifetime, but now he deserves the full star treatment. Carner owes that to him.