Like the other musical arts, jazz is more than just a collection of notes, chords and rhythms. When the conditions are right, jazz can take on an enriching spiritual quality that affects the musicians who create it and—again under the right circumstances—the audience which hears it. Starting in the 1960s, Charles Lloyd found a way to convey that spirituality to audiences, captivating large crowds in venues like the Monterey Jazz Festival and the Fillmore East. As his career developed (with periods away from the music scene when he explored his inner being in relative isolation) that deep spirituality has only grown more profound. In the new documentary, “Arrows into Infinity”, Lloyd’s greatness is measured by his impact on audiences and other musicians. Significantly, no one really explains in purely musical terms why Lloyd’s late Sixties quartet was so phenomenally successful while other jazz ensembles barely survived. Perhaps there is no definitive musical answer. However, one audience member from the Monterey “Forest Flower” concert articulates the extra-musical effect Lloyd’s group had on him: despite the cold temperatures at the outdoor festival, Lloyd’s music brought such spiritual warmth that he took off his jacket midway through the performance.

Like the other musical arts, jazz is more than just a collection of notes, chords and rhythms. When the conditions are right, jazz can take on an enriching spiritual quality that affects the musicians who create it and—again under the right circumstances—the audience which hears it. Starting in the 1960s, Charles Lloyd found a way to convey that spirituality to audiences, captivating large crowds in venues like the Monterey Jazz Festival and the Fillmore East. As his career developed (with periods away from the music scene when he explored his inner being in relative isolation) that deep spirituality has only grown more profound. In the new documentary, “Arrows into Infinity”, Lloyd’s greatness is measured by his impact on audiences and other musicians. Significantly, no one really explains in purely musical terms why Lloyd’s late Sixties quartet was so phenomenally successful while other jazz ensembles barely survived. Perhaps there is no definitive musical answer. However, one audience member from the Monterey “Forest Flower” concert articulates the extra-musical effect Lloyd’s group had on him: despite the cold temperatures at the outdoor festival, Lloyd’s music brought such spiritual warmth that he took off his jacket midway through the performance.

Lloyd has had a profound effect on fellow musicians. Certainly, his understated leadership was a key element in the development of future jazz greats Keith Jarrett, Cecil McBee and Jack DeJohnette. Lloyd also came out of semi-retirement to build up the career and renown of pianist Michel Petrucciani (there are a few touching clips of the two men playing and relaxing together). Unlike other jazz mentors, Lloyd’s presence could also transform established players into deeper musicians (to cite just one example, think of how Billy Higgins’ legacy was infinitely richer because of the late career albums he recorded with Lloyd). In one enlightening segment, drummer Eric Harland talks about the trio Lloyd formed with Harland and Indian tabla master Zakir Hussain. Harland says that he really didn’t know what to play amidst Lloyd’s free improvisations and Hussain’s complex rhythms, and it took him some time to find the answer. In the performance clip of the group, we see that part of the solution went beyond the instruments—Harland plays piano throughout and Lloyd plays drums through part of the work. The film also makes it clear that Harland also found ways to interact with Lloyd and Hussain from behind the drumset. What it doesn’t tell us is the sound Lloyd had in mind when he formed the group.

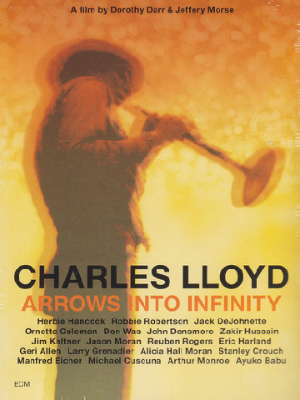

The film was co-directed by Lloyd’s second wife, Dorothy Darr. Despite her obvious closeness to her subject, Darr and her co-director Jeffery Morse keep the film honest and objective. At 112 minutes, the film is longer than most jazz documentaries, but the breezy pace and the superb collection of performance clips keeps the film moving. The editing has several jump-cuts, and the overall chronology is a little jumbled. The cinematography switches between black and white and color—and in a couple of spots, a monochrome image is swiftly converted to color). The sound is in Dolby Digital 2.0 (the box erroneously lists a 5.1 soundtrack) and the package includes a color booklet with full credits, notes from the filmmakers and Lloyd’s ECM discography. The latter leads me to one further note: if your music library does not include several of Lloyd’s recordings, the discussions and music in this film will make you want to get them! That is a most rewarding side effect.