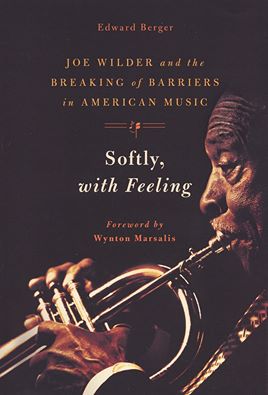

It’s not too surprising that jazz historian Ed Berger and trumpeter Joe Wilder were good friends before they became biographer and subject. Wilder was a dependable big band lead and section player before obtaining jobs in Broadway pit orchestras and the studio orchestra for ABC-TV. Up until a year or so ago, Berger was the Associate Director of the Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies. While each could have found more lucrative positions, they preferred to dedicate their lives to the greater good of music, and were obviously happier with the respect of their colleagues than becoming better known to the public at large. Thankfully, Berger realized that Wilder had an important story to tell, and the result is a superb biography, “Softly With Feeling” (Temple), which contrasts Wilder’s enormous breakthroughs and his humble demeanor.

It’s not too surprising that jazz historian Ed Berger and trumpeter Joe Wilder were good friends before they became biographer and subject. Wilder was a dependable big band lead and section player before obtaining jobs in Broadway pit orchestras and the studio orchestra for ABC-TV. Up until a year or so ago, Berger was the Associate Director of the Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies. While each could have found more lucrative positions, they preferred to dedicate their lives to the greater good of music, and were obviously happier with the respect of their colleagues than becoming better known to the public at large. Thankfully, Berger realized that Wilder had an important story to tell, and the result is a superb biography, “Softly With Feeling” (Temple), which contrasts Wilder’s enormous breakthroughs and his humble demeanor.

The book’s tone is sunny in its opening pages. It begins with a valedictorian forward by Wynton Marsalis, and then moves into a breezy discussion of Wilder’s childhood in and around Philadelphia and his early musical experiences. It is in the second chapter, which opens with Wilder’s secondary education at the Mastbaum Vocational and Technical School, that the narrative finds its main theme. Wilder was one of a handful of black students at the school, and his technical expertise had won him a chair in the solo trumpet section of the symphonic band. While a representative of an instrument company was visiting the campus to photograph the student ensembles, the school director had a manufactured tantrum, pretending that Wilder did not belong in the solo section with the white students. While the other students (including Buddy DeFranco) defended Wilder, it was the first of many racial incidents that rattled the young trumpeter. Wilder left the school after a year. Officially, the reason was his need to help support his family, but the ugly incident described above was certainly another reason.

While Wilder’s original aspiration was to be a classical trumpeter, there were no opportunities for black musicians in symphony orchestras of the time. After leaving school, Wilder joined a succession of big bands, including those of Lionel Hampton, Jimmie Lunceford, and Dizzy Gillespie, where his advanced sight-reading made him a vital part of each trumpet section. Wilder had had some experience in jazz at this point, but he tended to fall back on classical patterns in the rare instances when he would have to improvise. Between his years with the big bands (including a later tour with Count Basie) and studies at the Manhattan School of Music, Wilder became a well-rounded trumpeter who could comfortably play in a wide variety of styles.

Ironically, it was a particularly odious gig that led to Wilder’s first professional breakthrough. Someone heard Wilder playing in the band of an archaic vaudeville revue, and recommended him for a job in the pit orchestra of a Broadway show. Wilder was not the first black musician to be hired for such a position, but he felt the pressure, especially from the racist stagehands. Wilder never shied away from speaking his mind, but he couched his comments within his dignified manner, so that he got his point across without losing his cool. Although he had to go back to the vaudeville show when the Broadway show closed, he was invited to join the pit orchestra of another Broadway show. This time, the show was a hit: “Guys and Dolls”. Wilder played the obbligato on “My Time of Day” in the show and on the original cast album. A few years later, he was hired to play for a Cole Porter musical, and when the producers asked Porter if he would permit a black man to play lead trumpet in the orchestra, the composer’s only question was “Can the man play my music?”

While Wilder’s name was not well-known to the jazz public, he had an excellent reputation amongst his fellow musicians. Trumpeter Billy Butterfield offered Wilder his first opportunity at ABC, when he asked Wilder to sub for him at a session. Apparently, Wilder so impressed the orchestra contractor that he was nearly offered a position on the spot, but Wilder thought that the summons to the contractor’s office was a joke, and ignored it. It wasn’t until Wilder was called for an additional series of ABC dates that he met with the contractor and was offered a permanent job. Once again, Wilder was one of the first black musicians to win such a position. The opportunity at ABC included performances on the classical program “The Voice of Firestone”, and it allowed Wilder to further his dream of performing orchestral material.

In the mid-sixties, Wilder was a charter member of the Symphony of the New World, a professional orchestra with a substantial number of black and female musicians. Berger relates Wilder’s experience with this group in the book’s longest chapter, and it offers Berger his best opportunity to display his skills as a researcher. Berger explores the history of black musicians in symphony orchestras, which by the late sixties, wasn’t very extensive. In 1969, two black musicians filed a law suit against the New York Philharmonic, claiming that they were bypassed in the audition process because of their race. Wilder was not a major part of this trial—he was still with Symphony of the New World at the time—but Berger rightly includes a detailed discussion of the trial because its issues held further ramifications for black musicians. In the trial’s exploration of previous racial issues, Wilder testified that he had been called to play concerts with the Philharmonic’s summer orchestra, but the schedule conflicted with his Firestone broadcasts at ABC. Wilder assumed that the contractor knew of the conflicts before calling, but obviously those intentions are hard to prove.

Towards the end of the volume, Berger takes several jazz critics to task for questionable arguments and leaps of logic, but in general, he spares Wilder of such criticisms. The testimony above is a case in point, but so is the discussion of Wilder’s interracial marriage. We learn that Wilder’s second wife was Swedish and several years younger than he was, and that they met when Wilder toured Europe with the Basie band. They courted by mail for a couple of years, and finally met in person again when she moved to New York to marry him. This was in 1957, when interracial marriages were still illegal in many states. Yet, all we discover about the marriage is that Wilder learned to speak Swedish and that eventually, his entire family spoke Swedish at home. We are left to imagine what horrors occurred when the couple and their children were outside the friendly confines of their apartment.

Berger’s friendship with Wilder coincided with the trumpeter’s emergence as a jazz soloist and leader. Berger tells about the recordings that he produced with Wilder as both leader and sideman, and gives detailed descriptions of the trumpeter’s first gig at the Village Vanguard. He also discusses Wilder’s tenure at Julliard (and his unusual but highly effective approach to teaching), his periods with the Lincoln Center and Smithsonian jazz orchestras, and his appointment as an NEA Jazz Master. Berger could easily have regaled his readers with anecdotes about his friend, but he wisely keeps his reserve, letting Wilder’s accomplishments speak for themselves.

Just three weeks before the book’s scheduled publication, Wilder died at the age of 92. [Berger later told me that the book was available on Amazon in April, and Wilder’s family read it to him at his bedside–TC.] Wilder had not played in public since 2011, but until his final illness, he was able to leave his apartment for social functions and concerts. Just how much Wilder could have done in the way of book signings and personal appearances is now a moot point, but there’s little doubt that Berger’s elegantly-written biography will raise awareness of this important but underappreciated jazz giant. I suspect that many jazz fans will read this book and discover that their record collections are missing several of Wilder’s best recordings. A surge in purchases of Wilder’s old recordings may not help Wilder himself, but it will help his survivors. Since Wilder started his professional career to support his family, he might have appreciated this extended coda to his legacy.