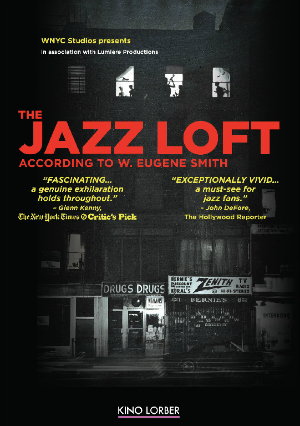

821 6th Avenue is an important location in New York City’s jazz history. It is not the location of a famous club, restaurant, recording studio or (legally speaking) a residence. Yet, in this building—located in the wholesale flower district—four flights above a drug store and a discount TV shop, was a jam session and rehearsal space hosted by painter David X. Young, composer Hall Overton, and photographer W. Eugene Smith. Young was the first person to live in this space, and while he was also the first to invite jazz musicians over, it was Smith that thoroughly documented the activities in the space, through a combination of remotely recorded open-reel tapes and thousands of candid photographs. Miraculously, a large portion of those recordings and pictures have survived, and they provide most of the visual and audio content of Sara Fishko’s documentary “The Jazz Loft, According to W. Eugene Smith” (Kino/Lorber).

821 6th Avenue is an important location in New York City’s jazz history. It is not the location of a famous club, restaurant, recording studio or (legally speaking) a residence. Yet, in this building—located in the wholesale flower district—four flights above a drug store and a discount TV shop, was a jam session and rehearsal space hosted by painter David X. Young, composer Hall Overton, and photographer W. Eugene Smith. Young was the first person to live in this space, and while he was also the first to invite jazz musicians over, it was Smith that thoroughly documented the activities in the space, through a combination of remotely recorded open-reel tapes and thousands of candid photographs. Miraculously, a large portion of those recordings and pictures have survived, and they provide most of the visual and audio content of Sara Fishko’s documentary “The Jazz Loft, According to W. Eugene Smith” (Kino/Lorber).

By the time Smith moved into the loft in 1957, he was widely recognized as one of the world’s greatest photojournalists. He had covered World War II for Life magazine (and suffered serious injuries while shooting pictures), and after the war, he created brilliant photo essays on subjects ranging from a country doctor to Albert Schweitzer. Smith insisted on full editorial control of his work, and a disagreement over the Schweitzer essay caused him to leave Life in 1954. He took on a project to document the city of Pittsburgh, but his compulsive personality caused him to stay much longer than expected and to take thousands of photos instead of the 100 required for the commission. Although he had a wife and children living in a lavish home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, he was uncomfortable with the constraints of family life. He had also neglected to pay taxes on the house, and Smith separated from the family when the eviction took place.

The lofts at 821 6th Avenue were, in the words of one interviewee, “a rat’s nest”. In addition to his extensive photo collection (much of which was tacked to the walls in layers) Smith had a huge record collection, and several tape recorders. Smith wired the building for sound, boring holes through the ceiling to record the music from Young’s loft one floor up. When a jam session began, Smith started the recorders and then took his still cameras upstairs to capture the images. Smith was an unassuming-looking man, so he blended in with the musicians and hangers-on, and he snapped photo after photo without disturbing the improvising musicians. Just as the loft was not technically a living space, it was not a performance space. Still, Smith took several pictures of interested listeners, including Norman Mailer and Salvador Dali.

The loft attracted some of the greatest jazz musicians of the era. Zoot Sims was a regular presence, as were Phil Woods, Gene Quill, Jimmy Giuffre, and Bob Brookmeyer. For many years, the musicians were not limited to beboppers; the loft embraced the coexistence of jazz styles and welcomed traditional and swing players to be part of the jam sessions. Overton, a Julliard faculty member who composed in both classical and jazz styles, brought his private students to the loft. One night, as Carman Moore was leaving after a lengthy composition lesson, Thelonious Monk walked into the loft. Monk and Overton were then collaborating for Monk’s Town Hall concert of 1959. Moore confesses that he hid in the loft and listened in as Monk and Overton worked. Viewers of this film get to have the same experience. In a fascinating sequence, we see and hear the two men discussing chords, listening to Monk’s original recording of “Little Rootie Tootie” (from which Monk’s piano solo was transformed into a shout chorus for the band) and finally, rehearsing the group for the concert. Smith’s photos and recordings bring a new perspective to the preparations for this classic performance, and it may stand as his most important jazz-related achievement.

As jazz and the world transformed in the next decade, the musicians who frequented the jazz loft were increasingly aligned with the free jazz movement. We hear and see tantalizing short bits of sessions featuring Don Ellis and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, but there is little discussion of what happened at the loft in the early to mid 1960s. The rehearsal space was discontinued sometime around 1965, and Smith was evicted from the loft in 1971. For those interested in more information about this part of the story, the two primary inspirations for the film, Sam Stephenson’s book “The Jazz Loft Project” and WNYC’s “Jazz Loft Project Radio Series” can be accessed using the links below each title.

While a film like this could become a parade of still photographs, director Fishko, cinematographer Tom Hurwitz and editor Jonathan J. Johnson keep the visual palette interesting with subtle zoom shots and photo effects. In addition, the interviewees offer a wide-ranging view of the relevance of the jazz loft scene and of Smith’s importance as a photographer. The music is fascinating, and while some excerpts from Smith’s tapes can be heard in a pricey CD box set, it would be good to have a single disc soundtrack available for this film. As is, the film offers an entertaining and informative look at the earliest of the New York jazz lofts, and of its unheralded documentarian, W. Eugene Smith.