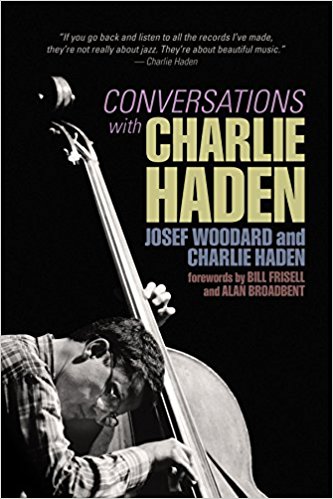

I only met Charlie Haden once. It was at an outdoor concert at Denver’s Botanic Gardens, and I was surprised at the quiet, melancholy lilt to his voice. He was as warm to me—a complete stranger with only aspirations to be a jazz historian—as he was to the veteran drummer Ginger Baker, who spoke to Haden right after me. I had never heard Haden’s voice before, and the only photos of him I’d seen showed Haden with fire in his eyes as he fervently made a point during a recording session. There was no question that Haden’s music carried great intensity and purpose, even within the confines of his laid-back Quartet West. Yet in the later years of his life, as various illnesses attacked his body, the quiet voice of Charlie Haden predominated over—but did not quell—the fiery intensity of his music. In the last two decades of Haden’s life, he was interviewed by journalist Josef Woodard for a wide variety of periodicals. Seventeen of those interviews have now been collected in a new book “Conversations with Charlie Haden” (Silman-James Press).

I only met Charlie Haden once. It was at an outdoor concert at Denver’s Botanic Gardens, and I was surprised at the quiet, melancholy lilt to his voice. He was as warm to me—a complete stranger with only aspirations to be a jazz historian—as he was to the veteran drummer Ginger Baker, who spoke to Haden right after me. I had never heard Haden’s voice before, and the only photos of him I’d seen showed Haden with fire in his eyes as he fervently made a point during a recording session. There was no question that Haden’s music carried great intensity and purpose, even within the confines of his laid-back Quartet West. Yet in the later years of his life, as various illnesses attacked his body, the quiet voice of Charlie Haden predominated over—but did not quell—the fiery intensity of his music. In the last two decades of Haden’s life, he was interviewed by journalist Josef Woodard for a wide variety of periodicals. Seventeen of those interviews have now been collected in a new book “Conversations with Charlie Haden” (Silman-James Press).

Haden was born in Iowa to a family of country music singers. The Haden family had a radio series, and when 2-year-old Charlie started singing harmony to his mother’s lullabyes, the family knew that he was ready to join the family on the radio. When he was a teenager, Charlie developed a form of polio, which paralyzed his vocal cords. Inspired by his brother, Charlie took up the string bass. After attending a concert of Jazz at the Philharmonic, Charlie became fascinated with jazz. He met members of the Stan Kenton orchestra after a gig, and while the band members tried to steer him away from the drudgeries of being a professional road musician, Charlie’s resolve became even stronger. He moved to LA in the late 50s, ostensibly for a college education, but started gigging fairly soon after his arrival, performing with one of his idols, pianist Hampton Hawes, on a gig led by Art Pepper. While working with pianist Paul Bley at the Hillcrest club, a young Texan with an unorthodox style and a white plastic alto sax came to sit in. That man was Ornette Coleman, who became one of Haden’s greatest friends and collaborators. Haden and Coleman left the club that night and went to Coleman’s apartment, where they played together for over 24 hours. Haden discovered a new sense of freedom with Coleman, and when the saxophonist formed his classic quartet with Don Cherry and Billy Higgins, Haden was Coleman’s first choice as bassist.

When the Coleman quartet traveled to New York for their famous engagement at the Five Spot, Haden encountered several legendary musicians—sometimes in surprising circumstances. Playing with his eyes closed, Haden suddenly realized a significant change in the style of the trumpet solo; while Cherry was soloing, Miles Davis came on stage and began improvising with the group! On another occasion, Haden opened his eyes after playing a solo to discover Leonard Bernstein sitting on the stage floor with his ear cocked towards the bass. Haden was an important element in the Coleman quartet, acting as the music’s harmonic center, and he could modulate to any harmonic center Coleman travelled. Yet, Haden could also play within the jazz tradition—a talent which shocked and delighted Roy Eldridge when the two played a job together. In 1969, Haden and pianist-composer Carla Bley formed the Liberation Music Orchestra to protest the politics and events of that troubled time. They reformed the group on several occasions whenever Haden felt the need to express his political views through music. Haden’s final recording was with the LMO (and with his passing, Bley has taken full leadership of the group). In the early 1970s, Haden was part of the legendary Keith Jarrett quartet with Dewey Redman and Paul Motian, and in the next decade, he formed his noir-ish Quartet West, which celebrated 1940s Los Angeles, and the great movies and pop singers of that era. He also recorded critically-acclaimed duet albums with Pat Metheny, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and Hank Jones. In the last decades of his life, Haden helmed an unorthodox but highly acclaimed jazz program at the California Institute of the Arts.

Woodard’s interviews usually found Haden on the brink of a new recording project or concert date (Fortunately, Woodard also caught up with the bassist just before a week-long Haden tribute at the 1989 Montreal Jazz Festival. The details are both welcome and illuminating.) Woodard also elicits touching and surprising memories from Haden. For example, Haden notes that he was friends with the legendary reedman Eric Dolphy; yet, a few paragraphs later, he admits that he never had the courage to sit in with Dolphy’s band. When discussing his program at CalArts, he tells Woodard that he encourages his students to think beyond jazz and to apply their talents to all forms of music. Considering that Haden recorded acclaimed albums of country music and Cuban boleros in addition to free and straight-ahead jazz, such advice carried a lot of wisdom. However, what drags this book down are the numerous retellings of the biographical details laid out above (In one interview, a publicist interrupted a Haden/Woodward interview to ask that the two men stop talking about Ornette Coleman and discuss the upcoming Haden album instead!) The book jacket indicates that many of these interviews appear complete in print for the first time. That’s fine for the individual interviews, but no one seemed to read this collection as a book. Some judicious editing would have greatly improved the flow of this narrative.

Unfortunately, the superb Haden documentary, “Rambling Boy” is not available in its complete form online or on disc. But until that film resurfaces (and when it does, grab it!) Woodard’s collection of candid and honest interviews offers the next best thing: the words of a passionate, humanitarian artist focusing on his then-current and eternally classic recordings. Read the book, listen to the recordings, and discover the soul of a great American artist, Charlie Haden.