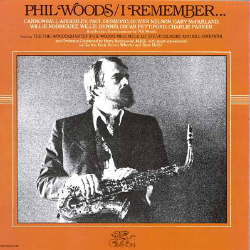

The 1970s were a rough time for jazz. By mid-decade, the music was just starting to re-establish itself after more than 10 years in a rock-dominated culture. A new batch of LP reissues emphasized jazz’s history, but by the time the reissue boom hit its peak, many of the featured artists had passed away. Phil Woods returned from a long period in Europe, moved to the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania, helped create the jazz arts organization COTA, and restarted his career in the US. By 1978, he was recording for the independent label Gryphon, and somehow he convinced the owners of that label to finance an album featuring his quartet and an augmented big band with string quartet. Woods had composed and arranged an album-length suite which paid tribute to the past masters who had inspired him. Recorded in March 1978 in London, and released in the following year, “I Remember…” remains one of Woods’ most concentrated and artistically successful albums.

The 1970s were a rough time for jazz. By mid-decade, the music was just starting to re-establish itself after more than 10 years in a rock-dominated culture. A new batch of LP reissues emphasized jazz’s history, but by the time the reissue boom hit its peak, many of the featured artists had passed away. Phil Woods returned from a long period in Europe, moved to the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania, helped create the jazz arts organization COTA, and restarted his career in the US. By 1978, he was recording for the independent label Gryphon, and somehow he convinced the owners of that label to finance an album featuring his quartet and an augmented big band with string quartet. Woods had composed and arranged an album-length suite which paid tribute to the past masters who had inspired him. Recorded in March 1978 in London, and released in the following year, “I Remember…” remains one of Woods’ most concentrated and artistically successful albums.

A rubato introduction by Woods’ quartet pianist Mike Melillo opens the suite in a pensive mood, but before the setting becomes too somber, Woods and the big band segue into the opening bars of “Julian”, a lively gospel-rock tribute to Cannonball Adderley. The band’s first big ensemble chorus grabs the listener’s attention with its bite and rhythmic precision. Gordon Beck contributes the first of many fine solos on electric piano before Woods roars in with a driving solo. An interlude for string quartet, flute and oboe momentarily bring back the melancholy tone, and then the gospel-rock feel returns with more inspired Woods, a reprise of the big band ensemble chorus, and an extended cadenza by Woods. It’s clear from this opening track that Woods considered Adderley a spiritual brother (despite their different approaches to improvisation, the two alto men achieved similar tones from their instruments). Yet, the following track “Paul” shows that Woods also had a special affinity for Paul Desmond. Desmond had passed away less than a year before Woods recorded his tribute, and the delicate writing for strings, oboe and horns is an elegant memorial. When Woods finally enters for a solo, the passion in his sound reveals the pain he still felt at the passing of his colleague.

“O.P.” was written in memory of bassist Oscar Pettiford, and Woods scores his melody to feature his quartet bassist, Steve Gilmore. The ensuing bass solo has all the rhythmic drive and melodic richness that Pettiford possessed. The brightly swinging chart features strong syncopated accents throughout, and when Woods returns for his solo, he builds the tension by incorporating similar accents. Woods has never received proper accolades as an arranger, but the ensemble backgrounds for Gilmore’s bass are exceptionally rich, using light touches of clarinets, strings, and both acoustic and electric pianos. The final composition on the LP’s first side, “Ollie” is the most ambitious piece on the album. Dedicated to Oliver Nelson, the piece opens with a blazing fast riff, followed by cooking solos by Melillo, Woods and Beck. But a little under halfway through the track, Woods makes a dramatic change. The tempo slows and the texture seems to fall apart. The eerie section which follows is based on one of Nelson’s favorite tone rows, and taken out of context, it could be mistaken for the score of a horror movie. One of the pianists doubles on harpsichord, and there are all kinds of bizarre percussion effects. It is certainly an unusual addition to this album, but the startling instrumental colors and the striking mood make it an interesting change of pace.

The second side returns to Woods’ familiar home turf with the sprightly bebop tribute to Charlie Parker, “Charles Christopher”. Kenny Wheeler is the trumpet soloist, and he seems to provide an abstraction of bop, rather a re-creation. Melillo also goes beyond the style for his sparkling chorus, before Woods chomps into the changes with gusto. The sheer abundance of ideas in Woods’ solo makes it clear that he loved playing over these chords, and it’s hardly surprising to note that this movement later became part of his quintet’s regular repertoire. “Flatjacks Willie” (for percussionist Willie Rodriguez) features a rare appearance by Woods on soprano sax, and a melody and orchestration reminiscent of Gerry Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band scores. Close listening reveals Woods’ fine integration of the strings into the ensemble: he skillfully mixes the orchestral colors so that the strings become part of the full texture rather than the usual “sweeteners”. And while it must have seemed strange to have two pianists on this recording, there’s obvious chemistry between Melillo and Beck, and it’s especially strong on this track.

“Sweet Willie” is a delight from beginning to end. Trombonist Dave Horler captures the sly wit of the song’s subject, Willie Dennis, in his opening cadenzas, and plays a finely crafted solo after the opening chorus. Woods’ spices up the standard big band voicings with a few menacing interludes, but for the most part, this is a joyful, straight-ahead romp. After solos by Melillo and Woods, the band plays a tricky set of unison lines against Bill Goodwin’s drums (and it should be noted that the orchestra contained some of the finest players in London at the time, including trumpeters Derek Watkins and Ian Hamer, trombonist Geoff Perkins, and saxophonists Ray Warleigh, Stan Sulzmann and Bob Efford). “Sweet Willie” ends with a delightful joke—and I wouldn’t dream of spoiling it for you! The final movement, “Gary”, is dedicated to Gary McFarland. This track has Beck’s only solo on acoustic piano and it is a beauty, combining the melodic statement and embellishment in an unaccompanied, rubato setting. When the slow tempo comes in, there is a lovely dialogue between the piano and the other instruments. There is a sudden interlude halfway through the track, which features Woods quoting “Parker’s Mood” at length. At first, this section seems jarring and out-of-place, but after the slow tempo returns, Woods skillfully merges all of the elements together, and he closes the suite with some of the most delicate fills he’s ever put on tape.

“I Remember…” is also a fitting memorial to Dr. Herb Wong, who passed away a few weeks before this article went online. Wong was a tireless supporter of jazz, and his liner notes for “I Remember…” represent some of the most scholarly and restrained writing of his career. They show Wong’s thorough knowledge of jazz history and his deep respect for Woods as a human and musician. The last reissue of this album included Wong’s notes, but I’ve never liked the re-mastered sound of this album on compact disc. The original sound on the LP is quite good, and those who would like to add this recording to their collection might want to seek out a used copy of the vinyl (at press time, there were several reasonably-priced copies available from Gemm, ebay and Music Stack). Besides, the gatefold LP cover makes it easier to read the liner notes! As for Woods, he is a true survivor, and in the years since “I Remember…”, he has written several more elegies for past jazz giants. He has recorded his memorial for Bill Evans, “Goodbye, Mr. Evans” on several occasions, and his latest big band album contains originals dedicated to Hank Jones, Art Pepper and Hank D’Amico. Perhaps it’s time for Woods to record another suite…