If Johann Sebastian Bach had lived in the present day, would he have been a jazz musician? This question has been tossed about by historians and fans for several years, and while there is no true answer, there are clear arguments on both sides. Those who say that Bach would have played jazz point to the linear style of his melodies, its recurring harmonic patterns (especially in the “Chromatic Fantasia” in D minor) and Bach’s love of improvisation. Those on the opposing side say that Bach was a traditionalist rather than a progressive and his genius was in the way he codified the Baroque movement in his music. They also point out that when Bach improvised, he would create a new piece with harmonic progressions devised on the spot, rather than—as Wynton Marsalis has quipped—start a casual jam with the viola player on “Ein Feste Burg”.

If Johann Sebastian Bach had lived in the present day, would he have been a jazz musician? This question has been tossed about by historians and fans for several years, and while there is no true answer, there are clear arguments on both sides. Those who say that Bach would have played jazz point to the linear style of his melodies, its recurring harmonic patterns (especially in the “Chromatic Fantasia” in D minor) and Bach’s love of improvisation. Those on the opposing side say that Bach was a traditionalist rather than a progressive and his genius was in the way he codified the Baroque movement in his music. They also point out that when Bach improvised, he would create a new piece with harmonic progressions devised on the spot, rather than—as Wynton Marsalis has quipped—start a casual jam with the viola player on “Ein Feste Burg”.

However, the best argument for Bach as a prototypical jazz musician has to be the music of the Swingle Singers. Ward Swingle and a group of fellow studio singers discovered that Bach’s music lent itself to jazz styles with very few modifications. Consider Swingle’s arrangement of Bach’s “Badinerie”. Originally a flute solo from the second Orchestral Suite, Swingle added a jazz feeling simply by changing the figured bass into a walking bass line. Then, by adapting Max Reger’s realization of the string parts to the middle voices, Swingle accentuated the rhythmic propulsion by adding scat syllables that evoked a 1930s rhythm guitar. Then he added Bach’s intricate solo line on top and the piece sounded like a new jazz composition.

However, it was more than just the arrangements that made the Swingle Singers an international phenomenon. First was the quality and agility of the voices. The solo line of the “Badinerie” is loaded with wide intervals and tricky ornaments, and it’s fairly certain that Bach never expected anyone to sing it. Yet, starting with Christiane Legrand, nearly every soprano in the history of the Swingle Singers has mastered this vocal obstacle course, singing it with apparent ease even at blistering tempos. (The video clip below features a brilliant performance by a recent incarnation of the group with Joanna Goldsmith-Eteson as soloist.) Equally important was the rhythmic vitality of the Swingles’ performances. Through the energy and accuracy of their ensemble rhythm, the Swingle Singers made the music dance. If Bach was meant to swing, the Swingle Singers found the way to do it. Finally, there were the scat syllables. Ward Swingle understood that Bach’s instrumental music didn’t need lyrics, and scat made the individual lines stand out. In fact, Swingle’s original arrangements did not have most of the scat syllables written in, and the eventual syllables used were those that the members found easiest to sing.

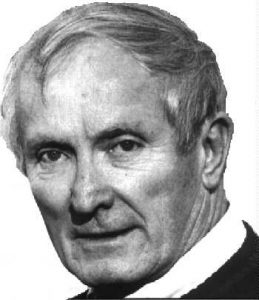

Ward Swingle (yes, that’s his real last name) was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1927. His father encouraged all of his children to sing and play instruments. Ward learned clarinet, xylophone and piano, while his brother Ira (known as “Eb”) and his sister Nina played trumpet and saxophone, respectively. In the mid-40s, all three siblings were hired for the Ted Fio Rito big band. After a brief stint in the Air Force, Ward attended the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, and then moved to France with his fiancée, violinist  Françoise Demorest. He was accepted into the master class of pianist Walter Gieseking, and later earned part of his living in Paris as a professional accompanist.

Françoise Demorest. He was accepted into the master class of pianist Walter Gieseking, and later earned part of his living in Paris as a professional accompanist.

While the Swingle Singers’ official debut came with their recordings of December 1962, the roots of the group date back to 1954, when Blossom Dearie formed the Blue Stars of Paris. The Blue Stars started as a vocal octet featuring Dearie’s own vocals and piano, along with Bobby Jasper, Fats Sadi, and several studio singers, including several future Swingle Singers. Christiane Legrand (sister of Michel Legrand) was already part of the group when Ward Swingle joined as a replacement for Jasper. Dearie and Sadi eventually left the group and Mimi Perrin became the new leader. Perrin reduced the group to six members and continued the group for a few years. The music of the Blue Stars was technically challenging, but fell into the general style of the other vocal groups of the era, including the Hi-Lo’s, the Four Freshmen and the Starlighters. The group performed live, but most of the singers made their primary income by singing background vocals in Paris’ recording studios.

In the late fifties, Quincy Jones encouraged Perrin to form a new vocal jazz group. Taking advantage of current recording technology, Perrin called the  sextet Les Double Six because the group would double-track their parts to create a vocal big band. Again, the group contained many future Swingle Singers, including Swingle, Legrand, Claude Germain and Jean-Claude Briodin. The first album was of Quincy Jones’ compositions, and Jones helped coach the group in the proper execution of his melodic lines. Perrin wrote intricate French lyrics for all of the compositions and the recorded solos. The recording is a true revelation. Not only does the Double Six cover all of the parts in Jones’ original big band scores, they accurately reproduce the nuances of the original soloists. The later recordings of the Double Six—some of which dovetailed with the earliest Swingle Singers recordings—included an album of jazz classics (with versions of “Fascinatin’ Rhythm” and “Boplicity” later sung by the Swingle Singers), a memorable collaboration with Dizzy Gillespie and a forgettable album of Ray Charles tunes. Because of its dependence on recording technology, there weren’t many Double Six live gigs, and those that did occur did not pay well. When the Double Six disbanded in 1965, Perrin stopped singing and became a professional translator.

sextet Les Double Six because the group would double-track their parts to create a vocal big band. Again, the group contained many future Swingle Singers, including Swingle, Legrand, Claude Germain and Jean-Claude Briodin. The first album was of Quincy Jones’ compositions, and Jones helped coach the group in the proper execution of his melodic lines. Perrin wrote intricate French lyrics for all of the compositions and the recorded solos. The recording is a true revelation. Not only does the Double Six cover all of the parts in Jones’ original big band scores, they accurately reproduce the nuances of the original soloists. The later recordings of the Double Six—some of which dovetailed with the earliest Swingle Singers recordings—included an album of jazz classics (with versions of “Fascinatin’ Rhythm” and “Boplicity” later sung by the Swingle Singers), a memorable collaboration with Dizzy Gillespie and a forgettable album of Ray Charles tunes. Because of its dependence on recording technology, there weren’t many Double Six live gigs, and those that did occur did not pay well. When the Double Six disbanded in 1965, Perrin stopped singing and became a professional translator.

In mid-1962, Swingle and seven other vocalists gathered to sight-sing through Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier”. All of the singers were instrumentalists as well as vocalists, and they were looking for a musical challenge greater than singing “ooh” and “ah” behind Charles Aznavour  andEdith Piaf. By December, the group’s personnel was Christiane Legrand and Jeanette Beaucomont (sopranos), Claudine Meunier and Anne Germain (altos), Claude Germain and Ward Swingle (tenors), Jean-Claude Briodin and Jean Cussac (basses). Pierre Michelot and Gus Wallez provided swinging accompaniment on bass and drums. Swingle approached Pierre Fatosme of Philips Records with the thought of making a “jazz Bach” record that they might sell to family and friends. Fatosme agreed, producing and engineering the group’s recordings. The album, “Jazz Sebastién Bach” was released in France with little fanfare. Then someone decided to send copies to radio stations in the United States. The 45 rpm single of “Contrapunctus 9” from Bach’s “Art of Fugue” (video below) became a huge hit in 1963, and within a month of its US release, the Swingle Singers made their first US tour (Ironically, the Double Six toured North America at the same time, and Perrin had to recruit new vocalists to replace those performing with the Swingle Singers). The Swingle Singers tour included several concerts and television appearances, and it culminated in performances for the Democratic National Convention in New York and a concert for President and Mrs. Johnson at the White House. The group won its first two Grammy awards that year, for Best New Artist and Best Choral Performance.

andEdith Piaf. By December, the group’s personnel was Christiane Legrand and Jeanette Beaucomont (sopranos), Claudine Meunier and Anne Germain (altos), Claude Germain and Ward Swingle (tenors), Jean-Claude Briodin and Jean Cussac (basses). Pierre Michelot and Gus Wallez provided swinging accompaniment on bass and drums. Swingle approached Pierre Fatosme of Philips Records with the thought of making a “jazz Bach” record that they might sell to family and friends. Fatosme agreed, producing and engineering the group’s recordings. The album, “Jazz Sebastién Bach” was released in France with little fanfare. Then someone decided to send copies to radio stations in the United States. The 45 rpm single of “Contrapunctus 9” from Bach’s “Art of Fugue” (video below) became a huge hit in 1963, and within a month of its US release, the Swingle Singers made their first US tour (Ironically, the Double Six toured North America at the same time, and Perrin had to recruit new vocalists to replace those performing with the Swingle Singers). The Swingle Singers tour included several concerts and television appearances, and it culminated in performances for the Democratic National Convention in New York and a concert for President and Mrs. Johnson at the White House. The group won its first two Grammy awards that year, for Best New Artist and Best Choral Performance.

When the group returned to Paris, Philips was anxious to follow-up on the Swingles’ success. “Jazz Sebastién Bach” was followed by “Going Baroque”, which contained the original version of the “Badinerie” and the Largo from Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto. The Largo became another mainstay of the Swingle Singers repertoire. Swingle told Legrand to imagine Miles Davis playing Bach’s melody. By simply displacing the melody and adding subtle soloistic embellishments, Legrand transformed the piece into a touching jazz ballad. Below is her performance of the piece from a 1969 appearance on Croatian television.

After “Going Baroque”, Swingle decided to apply his vocal jazz style to later composers. Swingle looked for music “that would swing on its own” and on  further albums, he successfully set music of Telemann, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann. “Anyone For Mozart” offered complete settings of the Piano Sonata # 15 in C Major and the serenade “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” (the latter has remained in the Swingles’ active repertoire since then). Both “Going Baroque” and “Anyone for Mozart” won Grammy awards for Best Choral Performance. In the autumn of 1966, John Lewis wrote both the instrumental and vocal arrangements for a recorded collaboration by the Modern Jazz Quartet and the Swingles. The following year brought an atmospheric album of Spanish music, including Legrand’s sensitive interpretation of the guitar solo from Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez”, a work also recorded by both Miles Davis and the MJQ. “Spanish Masters” also featured Swingle’s first appearance as featured soloist, on Granados’ “Rondalla Aragonesa” (With a few notable exceptions, Swingle limited his solo features so he could focus on leading the group). In 1968, the Swingles recorded an album of Christmas music, “Noëls Sans Passeport”. As the raw material was a group of songs rather than fully-written compositions, Swingle wrote his first “from scratch” arrangements for the group for this album.

further albums, he successfully set music of Telemann, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann. “Anyone For Mozart” offered complete settings of the Piano Sonata # 15 in C Major and the serenade “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” (the latter has remained in the Swingles’ active repertoire since then). Both “Going Baroque” and “Anyone for Mozart” won Grammy awards for Best Choral Performance. In the autumn of 1966, John Lewis wrote both the instrumental and vocal arrangements for a recorded collaboration by the Modern Jazz Quartet and the Swingles. The following year brought an atmospheric album of Spanish music, including Legrand’s sensitive interpretation of the guitar solo from Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez”, a work also recorded by both Miles Davis and the MJQ. “Spanish Masters” also featured Swingle’s first appearance as featured soloist, on Granados’ “Rondalla Aragonesa” (With a few notable exceptions, Swingle limited his solo features so he could focus on leading the group). In 1968, the Swingles recorded an album of Christmas music, “Noëls Sans Passeport”. As the raw material was a group of songs rather than fully-written compositions, Swingle wrote his first “from scratch” arrangements for the group for this album.

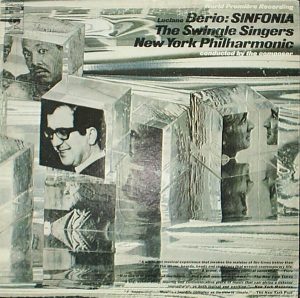

1968 also brought a major work into the Swingle Singers repertoire. Luciano Berio was introduced to the recordings of the Double Six and the Swingle Singers through fellow composer Louis Andriessen. Intrigued by the Swingle Singers’ virtuosity, Berio included the group in his composition, “Sinfonia”.  Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for its 125th anniversary, the work calls for a very large orchestra and the eight amplified voices of the Swingle Singers. In addition to traditional singing, the score calls for the Swingles to speak, shout and whisper. The scherzo is the best-known movement of the piece with its whirling maelstrom of musical quotes from composers ranging from Bach to Boulez, all set on top of the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony. There is a running commentary written by Samuel Beckett (originally spoken by Ward Swingle) but the text spoken by the other Swingles includes bits of graffiti found after the Paris riots of 1968. The world premiere recording earned another Grammy award for the group. “Sinfonia” is not for all tastes, but mainly due to the Swingle Singers’ participation, it has been performed more often than any other classical work of its time (Ward Swingle estimates that the Swingle Singers have done about 200 performances of the piece since its premiere). Below is a video of the Scherzo from a 2007 Italian performance.

Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for its 125th anniversary, the work calls for a very large orchestra and the eight amplified voices of the Swingle Singers. In addition to traditional singing, the score calls for the Swingles to speak, shout and whisper. The scherzo is the best-known movement of the piece with its whirling maelstrom of musical quotes from composers ranging from Bach to Boulez, all set on top of the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony. There is a running commentary written by Samuel Beckett (originally spoken by Ward Swingle) but the text spoken by the other Swingles includes bits of graffiti found after the Paris riots of 1968. The world premiere recording earned another Grammy award for the group. “Sinfonia” is not for all tastes, but mainly due to the Swingle Singers’ participation, it has been performed more often than any other classical work of its time (Ward Swingle estimates that the Swingle Singers have done about 200 performances of the piece since its premiere). Below is a video of the Scherzo from a 2007 Italian performance.

The success of “Sinfonia” led several composers to write for the Swingle Singers, some by direct commission from the group. Berio wrote two more pieces for the Swingles, both a cappella: “A-Ronne” features more speaking than singing, but is constructed in a musical manner, and “Cries of London” combines old merchant calls with 20th century vocal techniques. André Hodeir’s “Bitter Ending” uses text from James Joyce’s “Finnegan’s Wake” in a modern jazz setting, and Michel Zbar’s “Swingle Novae” combines jazz, electronic music and Berio-esque orchestral writing. Ben Johnston’s “Sonnets of Desolation” sets the final four sonnets of Gerald Manley Hopkins in an a cappella setting. Azio Corghi created his abstract ballet score “Mazapegul” for oboe and the Swingle Singers, and Pascal Zavaro’s rhythmic “Déjeuner sur l’herbe” was commissioned for the group’s 40th anniversary.

Throughout the 60s and early 70s, the Swingle Singers maintained a hectic schedule of international touring and recording. A second album of Bach was issued in 1968, followed by a collection of American music, which included the first—wordless—version of Swingle’s folk song pastiche, “Country Dances”. Now fully lyricized, “Country Dances” continues to be a favorite “Swingle oldie” that never fails to challenge the singers and delight the audience. Below is a 2009 performance, introduced by Sara Brimer.

The Swingles’ final album for Philips was “The Joy of Singing”. While the version of Vivaldi’s “Spring” concerto from “The Four Seasons” was hyped by the record company, the most interesting tracks are the versions of the Allegro movement of Bach’s Double Violin Concerto and Mozart’s Overture to “The Marriage of Figaro”, which call for 12 and 20 voices, respectively. These were the Swingle Singers’ first attempt at multi-track recording, a concept which Swingle had first tried with the Double Six and would revisit on the late 70s album, “Swingle Skyliner.”

In 1973, the original French Swingle Singers disbanded. Their recordings had covered an admirable range of musical styles, and Swingle was anxious to add lyrics to the Swingle Singers sound. Legrand, who had married Pierre Fatsome shortly after the Swingles formed, was eager to spend more time at home with her family, and she generally limited her future work to the studios. In 1975, she formed a new group, QUIRE, a four-voice studio group which, through extensive overdubbing, recreated classic jazz recordings note for note, using Swingle-style scat in place of the lyrics. QUIRE only recorded one album, RCA’s “QUIRE…is a Choir”, which can still be found in used record bins and online. Both Legrand and Swingle created and recorded arrangements of Dave Brubeck’s “Blue Rondo A La Turk” and the recordings make for a fascinating comparison (Legrand’s version is the opening track on the LP; Swingle’s version is on the CD, “Live in New York”).

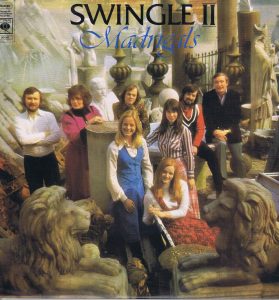

Swingle moved to England and formed a new octet, variously called Swingle 2 or Swingle II. Swingle wanted to tap into the English choral tradition and many of the vocalists in the new group were alumni of the great British choral schools. The English singers could sight-read as well as the French singers, but were less skilled in microphone technique and jazz styles. Swingle quickly taught the group how to sing on mikes, but many of the English Swingle Singers have had occasional problems performing straight-ahead swing. The English group has had much more turnover than its French predecessor. In the French group, many of the same singers remained for several years, but in the English group, many of the singers started their professional careers with the Swingles and then moved on to other opportunities. However, a few members like soprano Olive Simpson, alto Carol Canning and basses David Beavan and Simon Grant have served longer tenures, helping to maintain vocal consistency amid the numerous personnel changes.

The group signed with CBS Records and their albums from 1973-1979 alternated between adaptations of classical works and covers of contemporary pop songs. While the pop recordings were originally a commercial venture dictated by CBS, the Swingle Singers have continued to record pop covers, even when running their own label. The pop albums of the 70s through the 90s are generally a mixed bag, including highlights like the Bee Gees medley on “No Time to Talk” (where Ward Swingle skillfully mixed three separate songs into one) and Jonathan Rathbone’s later arrangements of “Fool on the Hill” and “I Will”/“Blackbird”. However, these minor triumphs sit alongside pointless recreations like “When I’m Sixty-Four” and ephemeral arrangements like the “10CC Medley”.

For the classical adaptations, Swingle made two major changes to the group sound. The majority of the English group’s repertoire now included lyrics, either those originally attached to the works or those added after the fact. This meant that the rhythmic intensity would be harder to achieve since the words included softer consonants than the percussive b’s and d’s used in the French group’s scat. Swingle assumed—correctly—that the style of the Swingle Singers was now so well-known that the group could perform primarily English lyrics without losing its international fan base. The other change was in the rhythm section. The French group always performed with discreet accompaniment by acoustic bass and drums. For the English group, Swingle added keyboards (sometimes played by Swingle himself) and changed the bass from acoustic to electric. The entire rhythm section sound became more prominent, as rock beats were introduced and synthesizer obbligati were added. Most of these accompaniments have not aged well. The tinkly sound of electronic harpsichord and the overbearing pop beats give a kitschy quality to the recordings. Thankfully, the excellent singing on the first classical recordings by Swingle 2 (which were a collection of madrigals with original scoring and lyrics, and “Rags and All That Jazz”, with works of Scott Joplin, Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton and Bix Beiderbecke set to new lyrics by Tony Vincent Isaacs) outweighs the accompaniments.

For the classical adaptations, Swingle made two major changes to the group sound. The majority of the English group’s repertoire now included lyrics, either those originally attached to the works or those added after the fact. This meant that the rhythmic intensity would be harder to achieve since the words included softer consonants than the percussive b’s and d’s used in the French group’s scat. Swingle assumed—correctly—that the style of the Swingle Singers was now so well-known that the group could perform primarily English lyrics without losing its international fan base. The other change was in the rhythm section. The French group always performed with discreet accompaniment by acoustic bass and drums. For the English group, Swingle added keyboards (sometimes played by Swingle himself) and changed the bass from acoustic to electric. The entire rhythm section sound became more prominent, as rock beats were introduced and synthesizer obbligati were added. Most of these accompaniments have not aged well. The tinkly sound of electronic harpsichord and the overbearing pop beats give a kitschy quality to the recordings. Thankfully, the excellent singing on the first classical recordings by Swingle 2 (which were a collection of madrigals with original scoring and lyrics, and “Rags and All That Jazz”, with works of Scott Joplin, Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton and Bix Beiderbecke set to new lyrics by Tony Vincent Isaacs) outweighs the accompaniments.

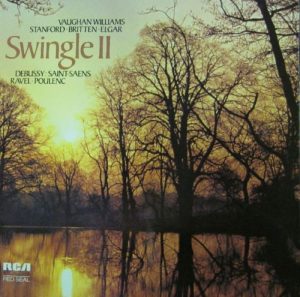

Things improved dramatically in 1976, with two superb albums. “Baroque”, released by CBS, went back to wordless vocals and  the music of Bach and Handel. Swingle doubled on keyboards, but added specific roles for the piano, instead of mere decoration. He added an original keyboard counter-line to his classic setting of “Air on the G String”, and on the opening movement of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto, Swingle played Bach’s original virtuosic keyboard part on piano. Also, the rhythm section moved back in the sound mix, which gave greater prominence to the voices and reduced the impact of the stiff rock beats. An even better album was recorded for RCA Red Seal. It was an a cappella album featuring straight performances of classic English and French choral works. Several of these works, including the Chansons of Debussy and Ravel, Vaughan Williams’ Shakespeare songs and the Britten “Hymn to St. Cecilia” were well-known to the group from their schooling, and Swingle had included the pieces in concerts of the time. The recordings are exquisite, with the close-miked singers performing these compositions flawlessly. The album, simply called “Swingle II” was never issued in the US, never reissued on CD, and is rather hard to find; however, it is well worth the effort to locate a copy.

the music of Bach and Handel. Swingle doubled on keyboards, but added specific roles for the piano, instead of mere decoration. He added an original keyboard counter-line to his classic setting of “Air on the G String”, and on the opening movement of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto, Swingle played Bach’s original virtuosic keyboard part on piano. Also, the rhythm section moved back in the sound mix, which gave greater prominence to the voices and reduced the impact of the stiff rock beats. An even better album was recorded for RCA Red Seal. It was an a cappella album featuring straight performances of classic English and French choral works. Several of these works, including the Chansons of Debussy and Ravel, Vaughan Williams’ Shakespeare songs and the Britten “Hymn to St. Cecilia” were well-known to the group from their schooling, and Swingle had included the pieces in concerts of the time. The recordings are exquisite, with the close-miked singers performing these compositions flawlessly. The album, simply called “Swingle II” was never issued in the US, never reissued on CD, and is rather hard to find; however, it is well worth the effort to locate a copy.

Go to Part 2

Go to Discography

Go to Swingles Gallery