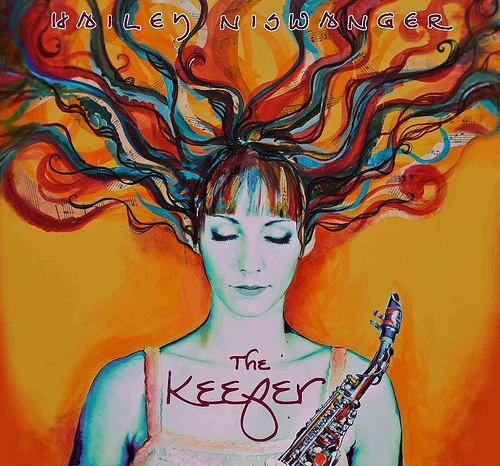

The adventurous music of saxophonist Hailey Niswanger might come as a surprise, considering her youthful, fresh-scrubbed appearance. Now 22, and recently graduated from the Berklee College of Music, Niswanger (pronounced “Nice-wonger”) has commenced her professional career with a second CD, the self-produced “The Keeper”. Accompanied by fellow Berklee alums Takeshi Ohbayashi (piano), Max Moran (bass), Mark Whitfield, Jr. (drums) and guest Darren Barrett (trumpet), Niswanger displays an engaging compositional style and a unique manner of improvising.

The adventurous music of saxophonist Hailey Niswanger might come as a surprise, considering her youthful, fresh-scrubbed appearance. Now 22, and recently graduated from the Berklee College of Music, Niswanger (pronounced “Nice-wonger”) has commenced her professional career with a second CD, the self-produced “The Keeper”. Accompanied by fellow Berklee alums Takeshi Ohbayashi (piano), Max Moran (bass), Mark Whitfield, Jr. (drums) and guest Darren Barrett (trumpet), Niswanger displays an engaging compositional style and a unique manner of improvising.

She is best known as an alto saxophonist, and on that horn, she has a rich sound in the lower and middle registers and a rather pinched sound on top. The sound is reminiscent of Phil Woods, but her solo style is much more abstract than Woods’. A typical Niswanger alto solo is filled with small melodic ideas that collide with each other as the solo builds in intensity. Sometimes she breaks up the collected motives with a heart-rending wail. She also plays soprano on several cuts, and I must say that I prefer her on the straight horn. Her sound is much more open and full here—the opposite of most soprano/alto doublers—and she tends to use more space in her solos, making them less intense and easier to follow. One can hear the clear influences of Steve Lacy and Jane Ira Bloom in her soprano work.

If Niswanger’s improvising style could be called non-melodic (at least in the traditional sense), one could not say the same about her compositions. Her written melodies are quite catchy, and she uses tempo changes to great effect. The opening track, “Scraps”, collects bits of melody that she had recorded over her phone. Yet, the piece holds together exceptionally well, even with sudden tempo jumps in the composition and an amazing—and very deliberate—accelerando during the solos, Niswanger tends to write about important people in her life, such as her late high school band director Jeff Cumpston (subject of the title composition), trumpeter Thara Memory (“Straight Up”) and arranger Norman Leyden (“Norman”). She also writes about inanimate objects, including parts of two childhood toys on the blues “B Happy”, and the Vincent Van Gogh painting “Les Peiroulets Ravine” in her evocative composition “Ravine”. The album also includes Niswanger’s fine arrangements of the 1947 “Milestones”, Monk’s “Played Twice” and a duet version of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day”. On the latter, Niswanger’s duet partner Ohbayashi could have played half as much piano for twice as much effect.

Given the press coverage Niswanger has received in the past few years, I’m quite surprised that “The Keeper” was not issued by a major label. While I can understand the artistic freedom that comes with making her own recordings, Niswanger might have been well-served by the production and distribution from a big company. To cite just one example, most of the background information above came from the press kit, and not from the album itself. A booklet with liner notes would have provided valuable information about both the music and the players. We in the press can (but don’t always) pass on that information, but not all potential listeners read CD reviews. From the evidence of “The Keeper”, Niswanger is an exciting young talent. Happily, she is committed to playing jazz, and it will be interesting to see where her muse takes her. Let us hope that she gets plenty of opportunities to be heard.