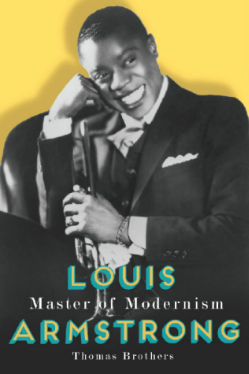

Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues” is an unquestioned jazz classic. Recorded June 28, 1928 for OKeh Records, it would have been considered a classic for any of Armstrong’s contributions: the opening solo cadenza that stretches over the entire range of the trumpet; the powerful lead in the first ensemble chorus; the understated scat vocal; the dramatic held high B-flat and the five unique descents in the final chorus. But this record had all of that and more. There is also an “x factor”: it’s not necessarily the musical elements such as the perfectly-balanced arrangement, or the influence from Armstrong’s performance which made the lesser musicians in his band play at their highest level. Rather, it is the tendency of this record to inspire jazz historians to project all kinds of extra-musical intentions onto Armstrong, even when the evidence seems to point in the opposite direction. In his new biography, “Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism” (Norton), Thomas Brothers claims that in the cadenza, Armstrong aims…for the supple quality of throbbing life itself, a feeling of movement where nothing is fixed, and everything is dissolving into something else and that the entire record was Armstrong’s method of slaughtering the ofay demons [white musicians who were stealing his music]. Such language (which in the latter case, originated with the notorious Chicago Defender journalist, Dave Peyton) sounds more appropriate to Joan of Arc, rather than Louis Armstrong. All of the evidence we have—including much of what Brothers relates elsewhere in his book—seems to indicate that Armstrong was happy to coexist with white musicians, and that he supported their efforts to emulate his style. I suspect that Armstrong would have been tickled by such overripe declarations, and would probably have handed the author a package of Swiss Kriss and said “Relax, Daddy, it’s just a record.”

Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues” is an unquestioned jazz classic. Recorded June 28, 1928 for OKeh Records, it would have been considered a classic for any of Armstrong’s contributions: the opening solo cadenza that stretches over the entire range of the trumpet; the powerful lead in the first ensemble chorus; the understated scat vocal; the dramatic held high B-flat and the five unique descents in the final chorus. But this record had all of that and more. There is also an “x factor”: it’s not necessarily the musical elements such as the perfectly-balanced arrangement, or the influence from Armstrong’s performance which made the lesser musicians in his band play at their highest level. Rather, it is the tendency of this record to inspire jazz historians to project all kinds of extra-musical intentions onto Armstrong, even when the evidence seems to point in the opposite direction. In his new biography, “Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism” (Norton), Thomas Brothers claims that in the cadenza, Armstrong aims…for the supple quality of throbbing life itself, a feeling of movement where nothing is fixed, and everything is dissolving into something else and that the entire record was Armstrong’s method of slaughtering the ofay demons [white musicians who were stealing his music]. Such language (which in the latter case, originated with the notorious Chicago Defender journalist, Dave Peyton) sounds more appropriate to Joan of Arc, rather than Louis Armstrong. All of the evidence we have—including much of what Brothers relates elsewhere in his book—seems to indicate that Armstrong was happy to coexist with white musicians, and that he supported their efforts to emulate his style. I suspect that Armstrong would have been tickled by such overripe declarations, and would probably have handed the author a package of Swiss Kriss and said “Relax, Daddy, it’s just a record.”

I’ve started with the above example because its style is so different from the rest of Brothers’ sober and thoroughly-researched book. More than any other biographer, Brothers has humanized Louis Armstrong. Armstrong was not a god that descended from the heavens to improvise perfectly-formed recorded solos designed to revolutionize jazz. Instead, he was a young man with little formal education, but with plenty of common sense and a rapidly developing musical gift. Brothers offers convincing proof that that most of Armstrong’s solos were not improvised in the recording studio, but worked out on the job at black theatres and cabarets. Armstrong also received classical training while living in Chicago, and Brothers highlights the traces of classical works and etudes within Armstrong’s recordings (including the solo cadenza on “West End Blues”). We’ve known for years that Armstrong considered recordings as a mere sideline, but unless videos of Armstrong at the Vendome Theatre or the Dreamland Café turn up, the records are our only documents of Armstrong as a developing musician. Brothers’ vivid descriptions of those venues and the music performed there may be our best substitute.

Race inevitably plays a role in the history of any 20th century African-American musician, and Armstrong was no exception. Brothers plays the race card freely and with an open hand. For each of Armstrong’s gigs, Brothers specifically notes whether the audience was white or black, and he theorizes that Armstrong adapted his style to the race of the audience. Brothers goes even further by claiming that Armstrong’s Hot Five recordings were designed for the black Southern audience and his big band forays into pop music (starting with “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”) were a deliberate attempt to attract white listeners. The record company may have thought so, but the testimony of white fans going into black neighborhoods to buy Armstrong discs tells a different story. Naturally, we don’t have a racial profile of Armstrong’s fans in the 1920s, but we can be sure that his music spoke to all jazz fans, regardless of skin color.

Brothers hits all the right points when discussing Armstrong’s unparalleled melodic gifts, his unique way of personalizing songs (both instrumentally and vocally) and his ability to anticipate harmonic changes. What he misses is Armstrong’s revolutionary concepts of rhythm and swing. In fact, Brothers accuses those who wish to study Armstrong’s rhythm separate from his melodies as being tied to primitivist thought. Nonsense! Modern swing can be traced directly to Armstrong, and it could well have been Armstrong’s greatest and most original innovation. Armstrong’s relationship to the beat was more advanced than any of his contemporaries, and he probably developed it through his own experimentation at home, on the bandstand, and in the recording studio. Nothing primitive or racist about that. Elsewhere in the book, Brothers stops just short of calling Leonard Bernstein a racist because he refers to Armstrong’s style as “simple”. Actually, when taken in context, Bernstein’s comment was not a back-handed compliment toward Armstrong, but a swipe at the over-scored “St. Louis Blues” concerto grosso that he had just led Armstrong, his All-Stars and the Lewisohn Stadium Orchestra through. (Bernstein’s quote can be heard beginning at 7:15 in the clip below—listen to the whole thing if you really want to understand his meaning.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cooR5vT3NzE

Brothers’ book covers the years 1922-1931, and as expected, he discusses Armstrong’s major recordings of the period. He discusses their musical strengths and weaknesses without relying on the dense musical analysis that turns laymen readers into page-turners. Even in the midst of his purple ravings on “West End Blues”, there is a thoughtful discussion of the record’s musical aspects and the reasons why it spoke to listeners. He dissects the duet with Earl Hines on “Weather Bird”, finding the precise spots that made it an endearing classic. Brothers also takes quite a bit of time referring to something he calls “the fixed and variable model”. In essence, the fixed element is a repeated rhythm over which the variable with contrasting rhythm is placed. Brothers states that this format comes from West Africa and it was brought to the New World by slaves. Perhaps so, but if the concept is applied to melody instead of rhythm, it can be found in Bach’s passacaglias and fugues, as well as any composed set of theme and variations! Did Armstrong use this method to build his solos? Of course he did. But to make it a direct link to Africa (as Brothers does) is tenuous at best.

“Master of Modernism” is the follow-up to Brothers’ earlier volume “Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans”. Neither the press release, the dust jacket or the book itself indicate whether Brothers intends to continue chronicling Armstrong’s life through the Swing Era and post-war periods, but I hope he does. Although there are plenty of Armstrong biographies (including the trumpeter’s own memoirs), Brothers’ unique mixture of social and musical reportage makes his input an important element into Armstrong’s work and jazz history in general. Whether or not you believe in all of his theories, Brothers’ writing enlightens the past like few others and makes you reconsider long-held opinions.