Amidst the hoopla surrounding this year’s Super Bowl in New Orleans, Wynton Marsalis presented a six-minute feature for “CBS This Morning” on the history of NoLa’s unofficial anthem, “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In”. Marsalis’ presentation had so much civic pride that it sounded like a commission from the New Orleans Chamber of Commerce rather than CBS. Despite input from jazz historian Bruce Raeburn, there was very little history in the feature, except for Marsalis’ assertion that the “Saints” was a nineteenth-century Protestant hymn. While there is much we don’t know about the origins of this song, chances are that it was created after a Catholic service.

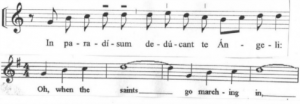

As Marsalis pointed out in the feature, New Orleans has had a long history of Catholicism. In the late 1800s, New Orleans Archbishop Francis Janssens established black Catholic parishes in the Crescent City. Black clergy officiated the services, which were spoken and sung in Latin. The famous tradition of the New Orleans brass band funerals originated around this time, and the collision of these two traditions may have given birth to the “Saints”. The key to this puzzle is found in the chant melody “In Paradisum”. In a Catholic requiem  mass, this is the only piece of music sung outside of the church. It is sung by the choir at the graveside, and the first four notes of the chant are exactly the same as the opening phrase of “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In”. So picture the scene: a brass band who marched the mourners to the church for the funeral now waits for the service to conclude so they can march the crowd back to town. They hear the “In Paradisum” chant and decide to use the opening phrase as part of an up-tempo song for the return home. If the above story sounds like a fanciful speculation, consider the melody of the “Saints”: the opening motive is really the most distinctive in the whole song (the music for the title line merely outlines the harmony), and note that the music for the words be in that number is a clever recasting of the opening idea.

mass, this is the only piece of music sung outside of the church. It is sung by the choir at the graveside, and the first four notes of the chant are exactly the same as the opening phrase of “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In”. So picture the scene: a brass band who marched the mourners to the church for the funeral now waits for the service to conclude so they can march the crowd back to town. They hear the “In Paradisum” chant and decide to use the opening phrase as part of an up-tempo song for the return home. If the above story sounds like a fanciful speculation, consider the melody of the “Saints”: the opening motive is really the most distinctive in the whole song (the music for the title line merely outlines the harmony), and note that the music for the words be in that number is a clever recasting of the opening idea.

If this was the way the song was created, it follows that other churches in New Orleans would include the song in their services. The lyrics have an antiphonal quality, which means they could have been improvised by a black preacher while lining out the hymns for his congregation. In their standard form, the lyrics have a strong connection to the Last Judgment and the book of Revelation. However, one will search Revelation in vain to find the image of marching saints; instead it is Satan’s army who marches around the saints, only to be wiped out by fires sent from Heaven. It’s hard to say where the concepts of marching saints originated, but it may have come from this song. It all depends on when the “Saints” was composed. Louis Armstrong remembered singing it at the Colored Waifs Home (the orphanage where he learned to play cornet) so that puts the probable composition date earlier than 1913. But as Armstrong historian Ricky Riccardi points out, there were many song titles featuring marching saints in the titles, including 1896’s “When the Saints Are Marching In” and 1908’s “When the Saints March In For Crowning”. We may never know if “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In” predates these other songs. Riccardi’s superb blog post (gratefully acknowledged as a source of this essay) also includes two of the earliest recordings of “Saints”, a 1923 version by the Paramount Jubilee Singers, and a 1928 blues version by Blind Willie Davis. The song was first published in 1927 in Edward Boatner’s collection “Spirituals Triumphant: Old and New”.

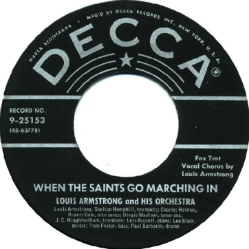

Louis Armstrong was primarily responsible for the song’s eventual popularity. His 1938 rendition for Decca is considered the first jazz recording of the song, and it is certainly one of the best. Armstrong retains the sacred setting of the tune, starting with a comic imitation of a preacher, and then singing the song with an antiphonal chorus. Along the way, trombonist J.C. Higginbotham

and alto saxophonist George Holmes are introduced as “brothers” by Reverend Armstrong. And as Riccardi notes, the drumming of New Orleans native Paul Barbarin is a special treat of this recording. Armstrong had planned to record the “Saints” for Okeh in 1931, but the producer wouldn’t let him record it, saying it was “too ahead of [its] time”. Armstrong countered that the Holy Roller church had sung the “Saints” up-tempo for years, but the producer didn’t think that the New York executives would know about the Holy Rollers or appreciate the record. As it turns out, Armstrong’s sister Beatrice (or Mama Lucy), was not very pleased about the Decca recording, which she thought was “tarting up a piece from church”. Armstrong reportedly replied by saying that there was nothing wrong with playing bingo in church!

and alto saxophonist George Holmes are introduced as “brothers” by Reverend Armstrong. And as Riccardi notes, the drumming of New Orleans native Paul Barbarin is a special treat of this recording. Armstrong had planned to record the “Saints” for Okeh in 1931, but the producer wouldn’t let him record it, saying it was “too ahead of [its] time”. Armstrong countered that the Holy Roller church had sung the “Saints” up-tempo for years, but the producer didn’t think that the New York executives would know about the Holy Rollers or appreciate the record. As it turns out, Armstrong’s sister Beatrice (or Mama Lucy), was not very pleased about the Decca recording, which she thought was “tarting up a piece from church”. Armstrong reportedly replied by saying that there was nothing wrong with playing bingo in church!

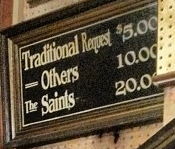

The explosion of “Saints” recordings and performances came with the Dixieland revival of the mid-1940s. Tom Lord’s online The Jazz Discography lists 1071 recorded versions of the song. No wonder it seems to  be the only jazz piece that the average travellng businessman seems to know or request. Many traditional groups call the song “the Monster”, likening it to the constantly-requested big band warhorse, “In the Mood”. There have been a few arrangements that have broken the standard mold, including the Terence Blanchard/Donald Harrison modal arrangement recorded on the 1984 album “Discernment”. Most audiences still want to hear the raucous Dixie version, even if it lacks originality. But if you want to hear the Preservation Hall Jazz Band play it, be sure to have a double sawbuck to drop in the tip bucket.

be the only jazz piece that the average travellng businessman seems to know or request. Many traditional groups call the song “the Monster”, likening it to the constantly-requested big band warhorse, “In the Mood”. There have been a few arrangements that have broken the standard mold, including the Terence Blanchard/Donald Harrison modal arrangement recorded on the 1984 album “Discernment”. Most audiences still want to hear the raucous Dixie version, even if it lacks originality. But if you want to hear the Preservation Hall Jazz Band play it, be sure to have a double sawbuck to drop in the tip bucket.