For years, bootleg recordings have been a necessary evil in the jazz world.  Many record collectors have bootlegs in their collections because they are willing to endure sub-standard audio, poorly written liner notes and inaccurate (or missing) recording information in order to hear otherwise unavailable recordings by their favorite artists. Recently, the problem has been compounded by European issues. The companies that issue these recordings take advantage of European copyright laws which allow recordings to go into the public domain 50 years after their original recording dates (the law has been updated, so that recordings made after 1963 do not enter public domain status for 70 years). Some of the European issues feature surprisingly good sound and well-researched liner notes. Still, the bottom line is the same for bootlegs and European issues: the musicians are not paid for their work. The painfully obvious solution is for legitimate record companies to issue superior editions of these recordings, which would make the unauthorized versions obsolete. Sony’s recent Miles Davis “Bootleg Series” has missed the mark in this regard, leaving off individual tracks or important concerts, forcing collectors to keep the bootlegs because the legitimate versions are incomplete. In contrast, Resonance Records has found the correct formula. Their latest release, “Wes Montgomery in Paris” (Resonance 2032), follows a distinguished list of historic titles now available in legitimate form, presented with extensive liner notes and exquisite fidelity.

Many record collectors have bootlegs in their collections because they are willing to endure sub-standard audio, poorly written liner notes and inaccurate (or missing) recording information in order to hear otherwise unavailable recordings by their favorite artists. Recently, the problem has been compounded by European issues. The companies that issue these recordings take advantage of European copyright laws which allow recordings to go into the public domain 50 years after their original recording dates (the law has been updated, so that recordings made after 1963 do not enter public domain status for 70 years). Some of the European issues feature surprisingly good sound and well-researched liner notes. Still, the bottom line is the same for bootlegs and European issues: the musicians are not paid for their work. The painfully obvious solution is for legitimate record companies to issue superior editions of these recordings, which would make the unauthorized versions obsolete. Sony’s recent Miles Davis “Bootleg Series” has missed the mark in this regard, leaving off individual tracks or important concerts, forcing collectors to keep the bootlegs because the legitimate versions are incomplete. In contrast, Resonance Records has found the correct formula. Their latest release, “Wes Montgomery in Paris” (Resonance 2032), follows a distinguished list of historic titles now available in legitimate form, presented with extensive liner notes and exquisite fidelity.

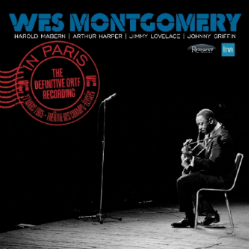

The new Montgomery album issues—in full—a legendary concert that has been bootlegged on several occasions (the Resonance booklet includes cover photos of 10 different unauthorized LPs of this material!). The performance was the guitarist’s only performance in Paris, and it featured him with the superb rhythm section of Harold Mabern (piano), Arthur Harper (bass) and Jimmy Lovelace (drums), along with guest tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin. The concert was recorded live by ORTF radio on March 27, 1965, and the mono mix captures the natural balance of the group with only a slight bit of distortion from Montgomery’s amplifier.

Montgomery hits the ground running with a brilliant solo on his “Summertime” contrafact, “Four on Six” and the energy remains high as Mabern follows with a exuberant piano solo. Montgomery was a self-taught musician who never learned how to read music. His solo on John Coltrane’s “Impressions” doesn’t follow the rules of modal improvisation, but the combination of his melodic invention and his rhythmic drive is quite astounding. Again, Mabern maintains the energy in his own solo over the rhythmic juggernaut that was Harper and Lovelace. “The Girl Next Door” opens with Montgomery unaccompanied on the verse, and then moves into a leisurely ballad tempo as the guitarist adds small filigrees to the melody. When Mabern enters on the second chorus, Montgomery emphasizes his improvised melody by playing in octaves. Mabern had only played a handful of gigs with Montgomery prior to this European tour, but they discovered a unique way to interlock their styles without getting in each other’s way. Their beautifully rendered dialogue makes “Girl Next Door” one of the highlights of the concert. On the bossa nova version of “Here’s That Rainy Day”, Montgomery plays the first chorus of his solo in lines two octaves apart (I can’t claim to have heard every extant Montgomery recording, but this is the first example I can remember of Montgomery using this unusual technique). The first half of the concert ended with “Jingles”, a piece Mabern names as his favorite piece in the band book despite its extreme difficulty. Montgomery leaps into these chord changes, showing his prodigious technique as he executes rapid passages of single lines, octaves and block chords over the speedy tempo. Mabern contributes an incisive solo before Lovelace takes over with an inspired set of exchanges with Montgomery, followed by a crisply executed solo.

After intermission, the quartet opened with Mabern’s “To Wane”, a tribute to Wayne Shorter which draws its melody from Shorter’s tenor solo on Art Blakey’s Impulse recording of “Alamode” (The spelling of Mabern’s title is a pun; he says the piece should wane like the moon!) Montgomery plays a lot of notes in his solo, but they don’t all sound; perhaps his hands weren’t quite back in sync after the break. As the solo progresses, the problem seems to go away. Nevertheless, Montgomery seems intent on saying a lot on this particular tune, and he never lets that passion subside. Mabern’s solo is also loaded with notes, but as he plays, he finds a repeated riff which helps delineate his ideas. His solo peaks with a brilliant sequence in block chords. Griffin joins the group for “Full House” (which was also the title track of a Riverside album featuring Griffin, Montgomery and the Wynton Kelly Trio). Montgomery finds his own repeated riffs to build his solo here. Griffin reminds himself of the changes while developing a moaning idea, then moves into a gritty and soulful mode to complete his solo. “Round Midnight” features an abstract piano introduction, an ornate but thoughtful melody chorus on guitar, and a tenor solo that opens with a little unexpected whimsy, but builds into a statement which adds more emotion with every passing bar. Montgomery’s ensuing solo is capped by an unaccompanied coda which temporarily breaks the mood but dazzles with beautifully-executed octave passages.

The quintet’s version of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Blue ‘n’ Boogie” omits all of Gilliespie’s written interludes, but makes up for it with uncompromising swing. Montgomery creates a fine solo using his usual building block approach of single lines, octaves and block chords. Then Griffin upstages everyone with an outstanding improvisation. Working with only bass and drums, the tenor man weaves complex rhythmic and melodic patterns in and over the solid 4/4 beat. Mabern and Montgomery re-enter after awhile, adding a simple rhythmic background figure. Then Griffin goes it alone, remaining on the blues changes, but swinging mightily all by himself! Perhaps realizing that they couldn’t top Griffin’s performance, the band returns to the Gillespie head, and then segues into their closing theme “West Coast Blues”. However, the capacity crowd at the Theâtre des Champs-Élysées was not satisfied, so the quartet returned with an encore of “Twisted Blues.” While the performance maintains the high standards of the performance, the overall results are a little underwhelming after “Blue ‘n’ Boogie”. However, the track includes the only bass solo of the night, and Harper’s imaginative contribution lifts the quality of the performance. As is noted in the booklet, one of the benefits of this edition is that it was mastered directly from the original tapes, which allows Harper’s work to be heard with utter clarity.

Wes Montgomery never returned to Europe, partially due to his intense fear of flying. Three months after this concert, he reunited with the Wynton Kelly trio for the seminal live sessions issued as “Smokin’ at the Half Note”. There would also be a memorable studio collaboration with organist Jimmy Smith, but most of Montgomery’s subsequent discography would feature him playing pop tunes with large orchestras. The Paris concert reviewed here displays Montgomery at his creative zenith. Over a half-century after it was recorded, it has finally received the deluxe treatment it deserves.