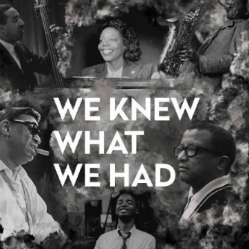

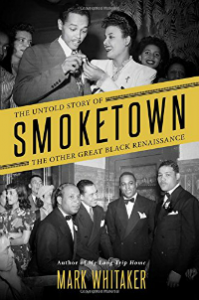

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania is a small city when compared to metropolises like New York, Boston and Philadelphia. However, the rich musical culture of the city’s black community produced an extraordinary number of jazz masters, including Earl Hines, Mary Lou Williams, Roy Eldridge, Billy Strayhorn, Kenny Clarke, Billy Eckstine, Erroll Garner, Art Blakey, Ahmad Jamal and George Benson. While most of these artists did their greatest work outside of the city, Pittsburgh provided a great environment for them to develop their craft. The public school system had been integrated since the late 19th century, and there were a number of fine teachers and mentors to guide young musicians. In addition, the Hill District—centered around Wylie Avenue—featured a robust jazz scene from the 1940s through the 1960s, where patrons could relax after a hard day’s work. The history and legacy of that era is celebrated in a new documentary “We Knew What We Had”, produced by MCG Jazz and currently airing on PBS and the World cable TV channel. (A home video release is expected to follow later in 2018). Concurrent with the documentary’s premiere is the publication of Mark Whitaker’s new book, “Smoketown” (Simon & Schuster). Although the book was not an offshoot of the documentary (and vice versa), Whitaker’s book amplifies some of the topics discussed in the film.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania is a small city when compared to metropolises like New York, Boston and Philadelphia. However, the rich musical culture of the city’s black community produced an extraordinary number of jazz masters, including Earl Hines, Mary Lou Williams, Roy Eldridge, Billy Strayhorn, Kenny Clarke, Billy Eckstine, Erroll Garner, Art Blakey, Ahmad Jamal and George Benson. While most of these artists did their greatest work outside of the city, Pittsburgh provided a great environment for them to develop their craft. The public school system had been integrated since the late 19th century, and there were a number of fine teachers and mentors to guide young musicians. In addition, the Hill District—centered around Wylie Avenue—featured a robust jazz scene from the 1940s through the 1960s, where patrons could relax after a hard day’s work. The history and legacy of that era is celebrated in a new documentary “We Knew What We Had”, produced by MCG Jazz and currently airing on PBS and the World cable TV channel. (A home video release is expected to follow later in 2018). Concurrent with the documentary’s premiere is the publication of Mark Whitaker’s new book, “Smoketown” (Simon & Schuster). Although the book was not an offshoot of the documentary (and vice versa), Whitaker’s book amplifies some of the topics discussed in the film.

The film packs an impressive amount of information into its 57-minute running time. The opening section is particularly strong, with historian Larry Glasco explaining the diversity of the blacks who emigrated to Pittsburgh (generally speaking, those who came from Virginia were better educated in classical music, but those who moved from the Deep South brought the influence of the blues), the geographic reason for school desegregation, and the economic boom that came to the city with the outbreak of World War II. The importance of Westinghouse High School’s music director, Carl McVicker, is discussed by his son, Carl, Jr., and several musicians recall the glory days of Wylie Avenue and the Hill. The center section of the film is a series of small biographical vignettes on Pittsburgh’s greatest jazz musicians, with special emphasis on Mary Lou Williams, Billy Eckstine, Art Blakey and George Benson (oddly, while Roy Eldridge’s photo appears, he is never mentioned on the soundtrack). There are also portions dedicated to the musicians who returned to Pittsburgh after seeking the limelight in New York. Two of these musicians, pianist Johnny Costa and guitarist Joe Negri, later made their names through their appearances on “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood”, while another, drummer Roger Humphries returned to bring the New York vibe back to his hometown, through playing and teaching. The urban renewal of the late 1950s reduced the Hill District to rubble, but as Glasco points out, Pittsburgh’s jazz scene did not end there; many of the businesses and clubs relocated and  thrived until 1968, when riots spawned by the assassination of Martin Luther King destroyed both the neighborhood and the relationships between white and black citizens.

thrived until 1968, when riots spawned by the assassination of Martin Luther King destroyed both the neighborhood and the relationships between white and black citizens.

Whitaker’s book casts a greater net on Pittsburgh’s black culture, including extensive sections on boxer Joe Louis and baseball player Jackie Robinson, as well as the massive influence wielded by the city’s black newspaper, the Courier. There are only two chapters dedicated to jazz, one relating the stories of Hines, Strayhorn and Lena Horne, the other focusing on Eckstine, Williams, Clarke and Garner (Eldridge gets a few paragraphs here too, but not nearly enough!). The longtime friendship of Strayhorn and Horne is well documented, as are the interweaving careers of Eckstine, Clarke, Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, but seasoned jazz readers might lose their trust in Whitaker when reading his odd retelling of the Gillespie “spitball story”. Suffice to say that Whitaker’s version is quite different from the supposedly authentic retelling offered by Gillespie, Jonah Jones and Milt Hinton in a Jean Bach film short.

Comparatively speaking, the film seems to be better researched than the book, although there are a few overstatements (No, George Benson’s singing was not one of the greatest things to happen in jazz!). Regardless of these flaws, the appearance of these two historical works helps to enhance Pittsburgh’s reputation in the jazz community. While Pittsburgh was never the “jazz mecca” claimed in the film, its strong history of black culture and great jazz deserves all of its new found attention.