The duo (or duet) remains one of the most venerable formats for jazz performance, despite (or perhaps, because of) the fact that there are very few rules that govern it. Theoretically, it might seem best for one of the musicians to play a chordal instrument, but in 1960, Al Cohn and Zoot Sims proved that they could swing and imply harmonies with just two tenor saxophones. Duos can be multi-generational as in the 1940 recordings of Duke Ellington and Jimmy Blanton. They can also span many jazz styles as on the 1967 album, “The Lee Konitz Duets”. The basic ingredients for a great jazz duo are little more than two talented musicians who want to play together, and a common jazz vocabulary. Just as duos themselves can widely vary, so can jazz duo albums. The two discs reviewed below each take a different approach to the duo format, and the very special dynamic contained within it.

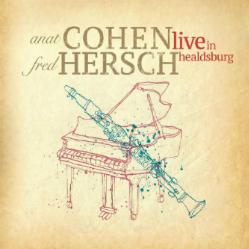

One of the annual highlights of New York jazz is pianist Fred Hersch’s series of duet concerts. Usually spread out over a week engagement at a nightclub, Hersch invites several of his favorite artists to “play in the sandbox” (to use Kate McGarry’s felicitous phrase). Clarinetist Anat Cohen has been one of Hersch’s longtime duet partners, and while their new album “Live in Heraldburg” (Anzic 61) was recorded in California, its artistic success certainly stems from all of their playing experiences in the Big Apple and elsewhere. From the first improvisations on the opener, “A Lark”, Cohen and Hersch  demonstrate their innate ability to interlock lines. At times, the combined sounds are almost like pointillistic art—little drops of paint spotted here and there in a seemingly random fashion, but eventually revealing their place in the overall picture. I first heard Hersch’s lyric “A Child’s Song” on a duet album with Jane Ira Bloom. It has been a regular part of Hersch’s repertoire for years, but the version with Cohen represents a fresh approach to the work. After the theme statement, which displays the song’s melody and chord structure, the duo suddenly abandons the harmony for a fascinating episode incorporating musique-concrete effects and wildly imaginative lines. Later, Hersch incorporates some of the chords, but he treats them freely, rather than in his own sequence. The piece was originally dedicated to Charlie Haden, and I’m sure the late bassist would have enjoyed this rendition. Cohen’s melancholy “The Purple Piece” moves seamlessly from theme to improvisation, showing how well these two musicians can inhabit the inner strata of a song. Far from the mysticism of Johnny Hodges’ original interpretation, “Isfahan” becomes a medium-tempo soft shoe with Hersch coyly disturbing the mood with sudden outbursts. There’s a delightful passage which starts with the two spontaneously bouncing a two-note motive back and forth; the way it develops is both surprising and amazing. “Lee’s Dream” features Cohen blowing bebop in her solo, and a duet passage where Hersch’s right and left hands take opposite melodic directions. Through an extended piano solo and a stunning clarinet cadenza, Cohen and Hersch show that Jimmy Rowles’ “The Peacocks” still offers many new avenues for exploration. The same general comment applies to Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz”, which is treated to a highly abstract reading. The encore, an understated reading of Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo”, might be the most traditional selection on the album, but it carries an indescribable beauty. Cohen will be Hersch’s first guest in this May’s duet invitational at the Jazz Standard in New York, but they are also touring as a duet this spring in several cities across the US. While I’m sure that the music will change from night to night, the creativity of these two artists makes me feel confident that the end result will be as inspiring as this live recording from the Sonoma Valley.

demonstrate their innate ability to interlock lines. At times, the combined sounds are almost like pointillistic art—little drops of paint spotted here and there in a seemingly random fashion, but eventually revealing their place in the overall picture. I first heard Hersch’s lyric “A Child’s Song” on a duet album with Jane Ira Bloom. It has been a regular part of Hersch’s repertoire for years, but the version with Cohen represents a fresh approach to the work. After the theme statement, which displays the song’s melody and chord structure, the duo suddenly abandons the harmony for a fascinating episode incorporating musique-concrete effects and wildly imaginative lines. Later, Hersch incorporates some of the chords, but he treats them freely, rather than in his own sequence. The piece was originally dedicated to Charlie Haden, and I’m sure the late bassist would have enjoyed this rendition. Cohen’s melancholy “The Purple Piece” moves seamlessly from theme to improvisation, showing how well these two musicians can inhabit the inner strata of a song. Far from the mysticism of Johnny Hodges’ original interpretation, “Isfahan” becomes a medium-tempo soft shoe with Hersch coyly disturbing the mood with sudden outbursts. There’s a delightful passage which starts with the two spontaneously bouncing a two-note motive back and forth; the way it develops is both surprising and amazing. “Lee’s Dream” features Cohen blowing bebop in her solo, and a duet passage where Hersch’s right and left hands take opposite melodic directions. Through an extended piano solo and a stunning clarinet cadenza, Cohen and Hersch show that Jimmy Rowles’ “The Peacocks” still offers many new avenues for exploration. The same general comment applies to Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz”, which is treated to a highly abstract reading. The encore, an understated reading of Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo”, might be the most traditional selection on the album, but it carries an indescribable beauty. Cohen will be Hersch’s first guest in this May’s duet invitational at the Jazz Standard in New York, but they are also touring as a duet this spring in several cities across the US. While I’m sure that the music will change from night to night, the creativity of these two artists makes me feel confident that the end result will be as inspiring as this live recording from the Sonoma Valley.

“Indigo” (Little Mystery 104), a new collaboration between trumpeter Nadje Noordhuis and vibraphonist James Shipp, explores the duo format from a different perspective. While the album still deals with the interaction between the two musicians, this music has been created by layers, with Shipp overdubbing synthesizer and percussion parts, and Noordhuis adding extra trumpet and flugelhorn parts, as well as electronic effects. Naturally, this does not reduce the authenticity of the overall music, but it changes the dynamic from the spontaneous arrangements of Hersch and Cohen to the creation of a unique sound world that just happens to be the work of two musicians. Much of this music feels like it is suspended in space. Noordhuis, one of the most gifted trumpeters on the current New York scene, displays a gorgeous trumpet tone throughout the album, while Shipp’s Gary Burton-inspired vibraphone offers a delicate crystal-like aura which weaves its way through the trumpet improvisations. Shipp’s synthesizer parts often supply a bass line or a general drone to support the rest of the music. All of these elements appear on the opening track “Old Mouse”. Shipp sets the scene with the sound of bell trees, and then brings in his vibes underneath. Noordhuis enters with the plaintive melody, and as the melody statement intensifies, Shipp adds bass synth and vibraphone overdubs. Shipp moves into a beautifully-sculpted solo, and Noordhuis gradually adds her trumpet below his improvisation. Before long, she moves into her own short solo which builds on the intensity generated by Shipp’s layers of sound. Esko Järvelä’s piece, “Terhin Ja Juhon Häävalssi” offers the best opportunity to hear Noordhuis and Shipp as a traditional jazz duet. The folk-like melody allows both musicians to breathe into the music. Shipp creates a delicate but full-sounding obbligato which initially supports and compliments Noordhuis’ expansive solo, but eventually develops into a full vibraphone solo. Egberto Gismonti’s “Palhaço” also includes a fine section of collective improvisation where listeners can hear the two musicians creating lines which support and enhance each other’s ideas. Noordhuis’ originals showcase her gift for composing extended lyric melodies (with “October” and “Wen Yora Way” both featuring notable tunes). The version of “Mercy Dance” makes the most of Noordhuis’ tune by bouncing the melody around from trumpet to vibes to synthesizer, while the title track gives Noordhuis a fine vehicle for extended free improvisation. Overall, Shipp’s tunes, “Old Mouse” and “Lounce Ainda” seem lighter in tone, but do not detract from the general scope of the album’s sound; however, the album’s rustic closer “South of Here” seems out of place amidst the otherworldly sounds of the preceding tracks. The overall design of this album is obviously quite different from the Cohen/Hersch disc, but both provide highly satisfying musical programs which reflect the strengths of their creators.

and Cohen to the creation of a unique sound world that just happens to be the work of two musicians. Much of this music feels like it is suspended in space. Noordhuis, one of the most gifted trumpeters on the current New York scene, displays a gorgeous trumpet tone throughout the album, while Shipp’s Gary Burton-inspired vibraphone offers a delicate crystal-like aura which weaves its way through the trumpet improvisations. Shipp’s synthesizer parts often supply a bass line or a general drone to support the rest of the music. All of these elements appear on the opening track “Old Mouse”. Shipp sets the scene with the sound of bell trees, and then brings in his vibes underneath. Noordhuis enters with the plaintive melody, and as the melody statement intensifies, Shipp adds bass synth and vibraphone overdubs. Shipp moves into a beautifully-sculpted solo, and Noordhuis gradually adds her trumpet below his improvisation. Before long, she moves into her own short solo which builds on the intensity generated by Shipp’s layers of sound. Esko Järvelä’s piece, “Terhin Ja Juhon Häävalssi” offers the best opportunity to hear Noordhuis and Shipp as a traditional jazz duet. The folk-like melody allows both musicians to breathe into the music. Shipp creates a delicate but full-sounding obbligato which initially supports and compliments Noordhuis’ expansive solo, but eventually develops into a full vibraphone solo. Egberto Gismonti’s “Palhaço” also includes a fine section of collective improvisation where listeners can hear the two musicians creating lines which support and enhance each other’s ideas. Noordhuis’ originals showcase her gift for composing extended lyric melodies (with “October” and “Wen Yora Way” both featuring notable tunes). The version of “Mercy Dance” makes the most of Noordhuis’ tune by bouncing the melody around from trumpet to vibes to synthesizer, while the title track gives Noordhuis a fine vehicle for extended free improvisation. Overall, Shipp’s tunes, “Old Mouse” and “Lounce Ainda” seem lighter in tone, but do not detract from the general scope of the album’s sound; however, the album’s rustic closer “South of Here” seems out of place amidst the otherworldly sounds of the preceding tracks. The overall design of this album is obviously quite different from the Cohen/Hersch disc, but both provide highly satisfying musical programs which reflect the strengths of their creators.