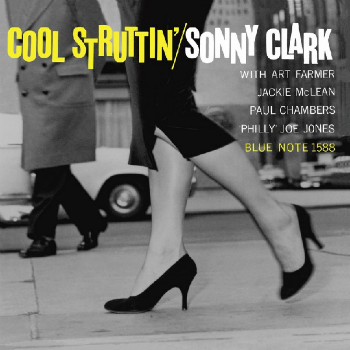

It is perhaps the most striking Blue Note cover ever made. The camera is set very low—either on the sidewalk or on the first step of a staircase. The photo is cropped so that no faces can be seen. The only object in focus is a woman’s right leg, framed at the top with a slit pencil skirt and at the bottom by a suede high heel shoe. Her left leg is blurred and in mid-gait, indicating motion. Walking near the curb is a man. His overcoat has a bottom hem which lines up with the bottom of the woman’s skirt. From the direction of the man’s walk, he is certain to cross paths with the woman somewhere on the outside of the frame. The only other object is a car, parked on the far side of the street, and facing in the opposite direction of the man and woman (most of the car is obscured by the legs of the man and woman, but a slight turn of the wheels indicates the direction of the vehicle). Like many others from the Blue Note catalogue, this cover was designed by Reid Miles and photographed by Blue Note’s co-owner Frank Wolff. In this instance, the female subject was Ruth Lion, the wife of Wolff’s Blue Note partner, Alfred Lion.

It is perhaps the most striking Blue Note cover ever made. The camera is set very low—either on the sidewalk or on the first step of a staircase. The photo is cropped so that no faces can be seen. The only object in focus is a woman’s right leg, framed at the top with a slit pencil skirt and at the bottom by a suede high heel shoe. Her left leg is blurred and in mid-gait, indicating motion. Walking near the curb is a man. His overcoat has a bottom hem which lines up with the bottom of the woman’s skirt. From the direction of the man’s walk, he is certain to cross paths with the woman somewhere on the outside of the frame. The only other object is a car, parked on the far side of the street, and facing in the opposite direction of the man and woman (most of the car is obscured by the legs of the man and woman, but a slight turn of the wheels indicates the direction of the vehicle). Like many others from the Blue Note catalogue, this cover was designed by Reid Miles and photographed by Blue Note’s co-owner Frank Wolff. In this instance, the female subject was Ruth Lion, the wife of Wolff’s Blue Note partner, Alfred Lion.

Then there’s the album title: “Cool Struttin’”. Had those words ever appeared together before the 1958 release of this album? The words are virtual antonyms: “cool” implying a nonchalant attitude, and “strut” meaning a proud walk. Could anyone actually do both at the same time? And if so, how would it look? Like the subjects in Wolff’s photo? Or something completely different? I’ve never seen anyone do a cool strut, but I know what it would sound like: the title track of the record inside that LP package. “Cool Struttin’” created a distinctive aural picture with a sexy hi-hat beat and a purposeful two-beat bass pattern in a medium-slow blues groove with funky piano chords. The sinewy melody line teased the listener by alternating a short three-note recurring motive with a long note that stretched out over several beats before returning to the motive.

When examining the personnel of the quintet, the album title makes a little more sense. The leader, pianist Sonny Clark (left), had just returned to the East Coast after several years in Los Angeles. While there, he had worked with Wardell Gray, Art Pepper, Teddy Charles, Serge Chaloff, Frank Rosolino and—in an exten ded tenure—Buddy De Franco. While none of these musicians were completely part of the West Coast “cool school”, it was (unfairly, but commonly) the style associated with Left Coast jazz musicians. The other West Coaster was trumpeter Art Farmer. Farmer had also played with Gray and Pepper (although not at the same time as Clark) and had been part of Roy Porter’s big band. Yet after touring Europe with the 1953 Lionel Hampton band—the same one that had Clifford Brown and Quincy Jones in the trumpet section—Farmer relocated to New York. Despite the years that Clark and Farmer spent in California, neither sounded like a typical West Coaster: in 1957 alone, Farmer had recorded with hard boppers Hank Mobley, Horace Silver and Benny Golson; Clark’s keyboard style had more than a passing resemblance to Silver’s and the two pianists could conceivably be mistaken for one another. If Clark and Farmer were the “cool” players, then the three New York-based musicians—alto saxophonist Jackie McLean, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones—represented the “strut”. McLean was just 26 years old at this session, and his bright searing tone was a striking contrast for Farmer’s meticulously sculpted lines. Chambers and Jones worked together every night in the Miles Davis Quintet, and while Clark’s style was far removed from Davis’ pianist, Red Garland, the Clark/Chambers/Jones trio instantly locked into tight, deeply swinging grooves.

ded tenure—Buddy De Franco. While none of these musicians were completely part of the West Coast “cool school”, it was (unfairly, but commonly) the style associated with Left Coast jazz musicians. The other West Coaster was trumpeter Art Farmer. Farmer had also played with Gray and Pepper (although not at the same time as Clark) and had been part of Roy Porter’s big band. Yet after touring Europe with the 1953 Lionel Hampton band—the same one that had Clifford Brown and Quincy Jones in the trumpet section—Farmer relocated to New York. Despite the years that Clark and Farmer spent in California, neither sounded like a typical West Coaster: in 1957 alone, Farmer had recorded with hard boppers Hank Mobley, Horace Silver and Benny Golson; Clark’s keyboard style had more than a passing resemblance to Silver’s and the two pianists could conceivably be mistaken for one another. If Clark and Farmer were the “cool” players, then the three New York-based musicians—alto saxophonist Jackie McLean, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones—represented the “strut”. McLean was just 26 years old at this session, and his bright searing tone was a striking contrast for Farmer’s meticulously sculpted lines. Chambers and Jones worked together every night in the Miles Davis Quintet, and while Clark’s style was far removed from Davis’ pianist, Red Garland, the Clark/Chambers/Jones trio instantly locked into tight, deeply swinging grooves.

The sensuous title track was actually the second title recorded by this group. The first was “Blue Minor” and the group’s immediate chemistry is evident from the coordinated way they play the melody. As McLean solos, Jones eggs him on with sharp rim shots. Jones instinctively backs off when Farmer takes the solo spotlight, letting him make his statement with the direct quality of his improvised lines. But as Farmer picks up steam near the end of his solo, Jones is alongside him with more rim shots. When Clark relieves Farmer, he offers up a soulful mix of Bud Powell and Horace Silver, spiced with his own distinctively clear piano tone. Chambers picks intriguing notes in his walking pattern, and at one spot, breaks up the pulse of straight quarter notes. His short bass solo displays his astonishing rich tone and fully developed melodic sense. By reprogramming the disc to play “Cool Struttin’” next, listeners can clearly hear that the special groove on “Struttin’” was rooted in what the band had just played on “Blue Minor”. Farmer’s supremely melodic solo on “Struttin’” ranks as one of his best, with great development of motivic ideas paired with some very soulful notes. McLean gets a deep resonating tone from his alto, but retains the biting sound on the upper overtones. Most of Clark’s comping here is fairly standard, but near the end of McLean’s solo, Clark backs him up with an insistent riff. Clark takes two solos on this track, the first one (appearing before Farmer) is rather low-key, but later, he digs deeper into the groove with strongly executed runs that stretch across most of the keyboard. Chambers starts his solo with the bow, then apparently changes his mind midway through and walks the rest pizzicato.

The next tune recorded was “Royal Flush”, which was not included on the original LP. I suspect that McLean’s fragmented solo was the reason why this track stayed in the vault for two decades. I’m not convinced that McLean was lost in the changes, but Farmer sounds much more confident as he arpeggiates the chords. Clark is fascinating behind the trumpeter, going way beyond typical bop comping with a unique mixture of counterpoint and riffs. Clark, the composer of all three songs recorded to this point, uses the melody particularly well in his solo here. As Chambers plays, both Clark and Jones offer a steady stream of background commentary. Jones shows off his crisp solo style before the band returns for the final theme. Jones leads off the next piece recorded, “Sippin’ at Bell’s”. Composed by Miles Davis and first recorded with Charlie Parker on tenor, the Farmer/McLean front line plays the arching melody with great precision. Clark plays another sparkling solo to lead off the improvisations, and then McLean regains his confidence with Jones splashing his cymbals in approval. In their general contour, Farmer’s lines sound like a tribute to Clifford Brown. Farmer said he learned a lot by playing alongside Brownie, and I wonder if Clifford would have been called for this date if he had lived long enough.

According to the original liner notes, Clark admired Rudy Vallee’s song “Deep Night”, but it wasn’t until he heard Powell play it at Birdland that he developed a way to play it in a jazz vein. Clark’s use of the trio alone for the melody statements and opening solo presents a welcome change in timbre. Indeed, it’s something of a shock when Farmer enters two and a quarter minutes into the track. Still, it works with Farmer’s reserved style building us up from the rhythm section to McLean’s more forceful presence. After his strong start, McLean loses his momentum and his lines become more fragmented and he starts to repeat himself as his solo closes. Then it’s back to the rhythm section, with more brightly articulated piano lines, a crackling drum solo, and the return of the melody. What magic this quintet brought to “Deep Night”—as well as the other pieces from this date—deserted them on the last track, “Lover”. Jones kicks it off with a fiery solo, and then he accentuates the phrase endings with fills. The introduction of waltz time at the bridge feels awkward, and the groove instantly dissipates, only to return in time for the solos. McLean clearly loves the brisk tempo and the juicy changes, and Farmer girds his loins for an intense solo ride. Somehow, the tempo seems wrong for a drum solo, but Jones gives it his best effort. Clark doesn’t get a solo, and Farmer plays a wrong note in the out-chorus, but the strange arrangement with the extended ending might have been the ultimate reason for rejecting this track.

I suppose that “Cool Struttin’” was conceived as just another blowing date, but the high quality of the music put it above the plethora of similar albums of the era. The personnel was highly unusual—it couldn’t have looked as good on paper as it sounded in the studio. Yet this particular combination of musicians playing this group of songs created an unquestioned masterpiece. Sonny Clark never led a better album, and it makes it all the more tragic that Clark was underappreciated in his lifetime. If not for this recording, Clark would likely be forgotten today. And Blue Note, a record label that got things right virtually every time, exceeded themselves with this recording. That music, that title, and oh, that cover….