Newton remained busy between August 1939 and March 1944 through a number of different engagements. In his book, “Who’s Who of Jazz”, John Chilton lists a mixed sextet at Lake George, New York during the spring of 1941, a quintet at the Hotel Pilgrim in Plymouth, Massachusetts in the following summer, a big band at the Mimo Club in New York in the autumn, and a combo gig at Kelly’s Stables at the end of the year. At least part of the Kelly’s Stable combo (including Flip Phillips on clarinet, George Johnson on alto, and Maxine Sullivan as guest vocalist) appeared with Newton on a radio broadcast from Charlotte, Michigan on April 9, 1941. What brought Newton and company to this small town seems lost to history, and while it is always good to have more Newton recordings, this aircheck is a disappointment. The broadcast includes extended versions of several tunes that Newton never recorded elsewhere, including “Blue Lou”, “Royal Garden Blues”, “Molly Malone” (a feature for Sullivan) and “Summertime”. While the sextet plays well as an ensemble, Newton sounds uninspired, playing proficient solos which lack the spark of his 1939 recordings. The broadcast was originally recorded on acetate discs, and what has survived is apparently a copy. The original discs were fairly worn when they were copied, and now the copy is also showing its age. The recording is marred by several skips, and the surface noise is significant. I don’t know if the original discs or the copies still exist, but if this aircheck could ever be restored and issued, it’s likely that both discs would be required to create an acceptable master.

Newton remained busy between August 1939 and March 1944 through a number of different engagements. In his book, “Who’s Who of Jazz”, John Chilton lists a mixed sextet at Lake George, New York during the spring of 1941, a quintet at the Hotel Pilgrim in Plymouth, Massachusetts in the following summer, a big band at the Mimo Club in New York in the autumn, and a combo gig at Kelly’s Stables at the end of the year. At least part of the Kelly’s Stable combo (including Flip Phillips on clarinet, George Johnson on alto, and Maxine Sullivan as guest vocalist) appeared with Newton on a radio broadcast from Charlotte, Michigan on April 9, 1941. What brought Newton and company to this small town seems lost to history, and while it is always good to have more Newton recordings, this aircheck is a disappointment. The broadcast includes extended versions of several tunes that Newton never recorded elsewhere, including “Blue Lou”, “Royal Garden Blues”, “Molly Malone” (a feature for Sullivan) and “Summertime”. While the sextet plays well as an ensemble, Newton sounds uninspired, playing proficient solos which lack the spark of his 1939 recordings. The broadcast was originally recorded on acetate discs, and what has survived is apparently a copy. The original discs were fairly worn when they were copied, and now the copy is also showing its age. The recording is marred by several skips, and the surface noise is significant. I don’t know if the original discs or the copies still exist, but if this aircheck could ever be restored and issued, it’s likely that both discs would be required to create an acceptable master.

If Newton was lackluster on the Michigan broadcast, he was certainly in top form at a jam session at Monroe’s Uptown House in New York on September 16, 1941. That night, the trumpeter played (at least) two tunes with the legendary pianist Art Tatum. Tatum’s unrivaled technique and sophisticated harmonic knowledge made him a formidable opponent at after-hours jams, and it wasn’t unusual for Tatum to completely obscure his fellow musicians (As Roy Eldridge once said of the pianist, “If you took a breath, he’d cut you!”). Newton not only holds his own throughout “Oh, Lady Be Good”, he matches Tatum’s inside jokes and outrageous extended chords on “Sweet Georgia Brown”. Newton came prepared—it sounds like he changed from a cup mute to a buzz mute between his first two solos on “Lady”—and he listened carefully to Tatum’s lines on “Sweet Georgia” to effectively answer with lines of his own. My favorite Newton spot is on “Sweet Georgia” follows a long Tatum solo where the pianist satirized the bop experiments occurring at Monroe’s during the period; Newton enters with a dotted quarter/eighth pattern that seems to mock Tatum’s frivolity. Tatum gets him back at the end of the track with a quote from “Buddy Bolden’s Blues”. Trumpet and piano throw ideas back and forth throughout the 12 minutes of combined track time, but they converge in unexpected ways and places. This wonderful recording, caught by Jerry Newman, is one of the treasures of jazz history, and no words can substitute for the joy of hearing this music. (Newman recorded the trumpeter on at least one other occasion. On a track called “Forniculi, Fornicular, Forniculate”, Newton plays seven choruses on the changes of “Tea for Two”. There are numerous stories of Newton stretching out like this at after-hours sessions, but no recordings—including this track—have ever been issued.)

Oh, Lady Be Good (Art Tatum)

Sweet Georgia Brown (Art Tatum)

Newton’s romance with Ethel Klein continued throughout this period, and the trumpeter sought gigs in Klein’s hometown of Boston. He played at the Savoy club sometime in 1941 and around that time, he made the acquaintance of three young Jewish jazz fans: Nat Hentoff, George Wein, and Paul Greenberg. All three men wrote loving memorials of Newton in their later years, Hentoff in his books “Boston Boy” and “The Jazz Life”, Wein in his autobiography “Myself among Others” and Greenberg in an unpublished collection of essays called “Long Days, Short Nights”. Newton became a mentor to each of these young men, offering wisdom on music, politics, athletics and life, as well as providing each a place to stay whenever they visited New York (although Newton was understandably peeved at Greenberg when the 17-year old showed up on his doorstep and proclaimed himself Newton’s new roommate!). The memories these men shared should be read on their own, but it is worth noting that Newton taught each of them a valuable lesson in the realities of being a black man in mid-20th century America. We have already noted that Newton became Hentoff’s unofficial bodyguard when the young man started an interracial relationship. When walking with Greenberg on a Boston street, Newton told the teenager to walk a half a block behind him, and to “run like Hell” if they were jumped. Wein remembers walking down a Manhattan street and noticing that Newton wanted to get a drink. Wein suggested a bar, but Newton, knowing the place’s white clientele, refused. When Wein asked why, Newton said “George, you’ve never been black one day in your life”. Over the years, each of these young men played a crucial role in Newton’s life; Hentoff and Wein through gigs in Boston, and Greenberg as a fellow member of the Communis t party.

t party.

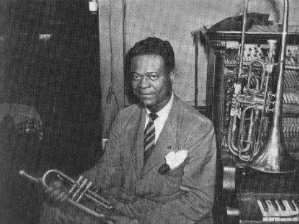

During the summer of 1941, Newton worked as a camp counselor and musician at Camp Unity, a Communist getaway near Poughkeepsie, New York. To fulfill the band obligations, he hired a group which included Sidney Bechet, Everett Barksdale, Arthur Herbert and Willie “the Lion” Smith. The Lion was not very impressed with the atmosphere. In “Music on My Mind”, he complains about the food (bad), the housing (a different tent every night) and the company (“a nest of commies”). After the first week, he grabbed a train back to New York and sent a new pianist to take his place. Unlike the Lion, Newton seemed to enjoy these vacations, and he worked at several summer camps over the next few years (the photo at right shows Newton with a group of young campers in July 1951; the racial integration is noteworthy for the period). Newton’s other activities during this period included a 1942 concert for Russian War Relief, several appearances on WNEW’s jam session series “Hot Jazz Matinee”, the first of several collaborations with dancer Mura Dehn, a broadcast with Art Hodes from Nick’s in Manhattan, an engagement in Boston from November 1942 through February 1943, and a return to Café Society in 1943. During the latter engagement, Newton worked with the great pianist Mary Lou Williams, and it was under her name that Newton finally returned to the recording studios.

The March 12, 1944 session was issued as “Mary Lou and Her Chosen Five”, and the band included two of Newton’s favorite hornmen, Vic Dickenson and Edmond Hall. In addition to Williams (who also arranged all of the pieces) the rhythm section featured Al Lucas on bass and Jack “the Bear” Parker on drums. The session was produced by Moe Asch, who shared Newton’s left-wing politics, and who would record the trumpeter on two more occasions over the next two years. “Lullaby of the Leaves” opens with a moody introduction with the horns playing background to Williams’ melody statement. Hall and Dickenson split a chorus, but Newton’s solo is the highlight of the track. The expected motivic development is there, but it is the way that Newton plumbs the emotional depth of the song with his wounded, soulful tone that makes this solo such an outstanding achievement. Williams must have loved Newton’s way with a ballad, for she created another slow episode for him as the introduction to the boogie “Little Joe from Chicago”. Newton makes the best of the opportunity with a lovely cup-muted statement. While Newton does not solo in the medium-tempo portion of the side, he can be heard leading the crisp ensemble figures and participating in the band vocal. Williams’ combo version of “Roll ‘Em” retains many of the riffs from her famous arrangement for the Benny Goodman Orchestra. Williams’ eight-to-the-bar piano is the main feature on this side, but while Dickenson and Hall each play fine solos, Newton’s chorus is marred by odd note choices and sloppy execution. In the early Fifties, Asch issued a 15-minute compilation of rehearsals and alternate takes for “Little Joe” and “Roll ‘Em”. There are a few ensemble figures that were cut from the final arrangements, a fair amount of chatter, several false starts, and full-length alternate takes of both titles. The Newton solo on the alternate of “Roll ‘Em” is marginally better than the master, but is still a poor effort for the trumpeter. His lyric lines also seem out of place on the light-hearted session closer, “Satchelmouth Baby”. In his earlier recordings, Newton effectively juxtaposed long legato phrases over bouncy rhythms, but on this recording, the effect falls flat. Was he discouraged with the way the session was proceeding? Was his lip failing him? We may never know, but something was clearly going wrong towards the end of the session.

Lullaby of the Leaves (Mary Lou Williams) FN solo

Little Joe from Chicago (Mary Lou Williams) FN intro

The recordings from James P. Johnson’s June 12, 1944 session were collected in a concept album for Asch titled “New York Jazz”. It represented the pianist’s interpretation of ragtime and stride music as they were played in the 1910s. Newton was the only horn player, and the rhythm section included Al Casey (guitar), Pops Foster (bass) and Eddie Dougherty (drums). “Hesitation Blues” represents an early version of the 12-bar form. Some of the verses sung here by Johnson also appeared on Louis Armstrong’s “2:19 Blues” and Jelly Roll Morton’s “Mamie’s Blues” (on his recording, Morton said that the piece was a favorite of Mamie Desdunes, a madam from New Orleans’ Storyville district). However, Johnson adds a second 12-bar section in a different key and with an alternate chord sequence. Newton plays an elegant introduction and accompanies the Johnson’s blues choruses, yielding to Casey in the second section. Newton closes the side with an explosion of raw emotion, squeezing and bending notes with great abandon to create a powerful blues statement. “Boogie Dream” is a gently flowing composition based on a pared-down version of the standard left-hand boogie patterns. The second half of the track includes a series of exchanges between Newton and Johnson. About a minute before the end, the piece seems to end, but it suddenly picks up again with a variation on the second section. Could this be part of an alternate take dubbed onto the master? It appears in the same manner on the master discs, so it’s hard to say. On the final album, Johnson performed Scott Joplin’s “Euphonic Sounds” as an unaccompanied solo, but a rehearsal take issued later on Folkways is a trio version with Dougherty providing a simple brush-on-snare background, and Newton joining in with a repeated motive on the final strain. Johnson had suffered a stroke a few years earlier, and I suspect that he suggested this version to ensure that his time would remain steady; apparently, Asch or the musicians convinced him that he could play the piece as a solo.

Boogie Dream (James P. Johnson) FN/JPJ exchanges and coda

“Four O’Clock Groove” is another relaxed piece, and Newton plays an open solo and an improvised duet with Casey. However, the tone of his horn sounds different, and discographer Bob Weir has suggested that Newton may be playing a flugelhorn on this track. That could be the case (Newton was given a flugelhorn by the family of a friend who died in World War II) but to my ears, the horn sounds more like a cornet. Regardless of the instrument used, the track gives us the rare opportunity to hear Newton playing in a relaxed, lyric style over several choruses. In addition to his solo, Newton and Casey engage in a delightful improvised dialogue. An alternate take from the session discs omits most of the Newton/Casey duet, leaving the guitarist to solo on his own, but also includes an additional Newton chorus at the end of the track. “The Dream” was written around 1890 by Jesse Pickett, and was a favorite song of lesbian prostitutes (one of the song’s many alternate titles is “The Bull Dyker’s Dream”). It is a slow, seductive tango, and Newton’s romantic melody statement is complimented with sparkling figures from Johnson’s keyboard. The rhythm swells in the second half of the track for Johnson’s solo and for Newton’s superbly-played coda. The session discs include a rehearsal take with solo spots for Newton omitted on the master, and a slower complete take which heightens the sultry mood but ran a little too long for a 12” 78. While Newton plays well throughout this session, his best solo comes on the final track, “Hot Harlem”, where he improvises brilliantly over a stop-time background. His horn is tightly muted, and he might be playing through one of his homemade mutes. His sound has more sizzle than with the buzz mute he used earlier, and Newton can be heard singing the pitches as his plays. Newton removes the mute for the coda, bring this superb session to a close.

Four O’Clock Groove (James P. Johnson) FN solo

Hot Harlem (James P. Johnson) FN solo

In February 1945, Newton was featured in a short article in the New York Times. Reporter Lucy Greenbaum told of Newton’s dedication for teaching music to neighborhood children. Newton collected broken instruments, repaired them for the kids and offered free private lessons. Newton hosted weekly jam sessions at the Pied Piper club (where he also appeared with Johnson) and a portion of the proceeds went to Greenwich House Music School, where he taught three days a week. Newton had taught students for some time, as evidenced by a commercially unissued disc recorded on July 1, 1944. The names of Newton’s accompanists are written in pencil on the acetate’s label with only first initials and surnames: J. Fales (trombone), J. Moneke (clarinet), H. Zuirk (piano) and H. Good (drums). Jazz historian and Newton scholar Dan Morgenstern believes that these players were Newton’s students, and he encourages any living survivors to contact the Institute of Jazz Studies to offer more information about the recording. One of the sides is a beautifully understated rendition of “Black and Blue” (a piece otherwise unrecorded by Newton). It is a prime example of Newton’s mature ballad style, and we are happy to offer a stream of this rare and special track.

Black and Blue (FN)

Buck Ram is best-known as the producer for the 1950s group, the Platters, but a decade earlier, he was one of the first A&R men for Savoy Records. The “Buck Ram All-Stars” date of September 18, 1944 truly lived up to its name, as it featured several of the top musicians on the New York jazz scene. While all of the musicians were swing players, many of them acted as transitional figures in the bebop movement. Newton and Shad Collins shared trumpet duties, with Tyree Glenn on trombone, Earl Bostic, Don Byas and Ernie Caceres on reeds, Red Norvo on vibes, Teddy Wilson on piano, Remo Palmieri on guitar, Slam Stewart on bass and Cozy Cole on drums. Ram was credited as composer for all four of the tunes recorded that day, although the arrangements were apparently uncredited. Newton solos on two tracks. On “Twilight in Teheran” he contributes a brief, but fiery cup-muted solo, placing most of his notes squarely on the beat. Newton’s solo on “Ram Session” uses another mute, possibly a bucket-style mute of his own invention. He follows Bostic, and contrasts the exuberant alto man’s wild phrases with an exquisitely sculpted solo based on classic phrase forms. It’s too bad that Newton didn’t have more room to play, but the arrangements were designed to give solo space to as many of the players as possible. This session features imaginative compositions and arrangements, along with several fine solos, and it should be heard in its entirety, even though Newton’s solo opportunities are quite limited. Discographies list alternate takes for all of the tracks, but they have never been issued on commercial discs.

Twilight in Teheran (Buck Ram) FN solo

Ram Session (Buck Ram) Earl Bostic and FN solos

Newton’s next visit to a recording studio came on October 10, 1944, when he appeared as a member of Hank D’Amico’s Sextet. D’Amico was primarily a big band and studio clarinetist, and this session was his debut as a leader. In addition to Newton and D’Amico, the band includes Don Byas (tenor sax), Dave Rivera (piano), Sid Weiss (bass) and Cozy Cole (drums). The group sound resembles the John Kirby Sextet, and as one of the tunes, “Sly Witch from Greenwich” was penned by Newton, I wonder if it was a piece he had written for the Kirby group years earlier. On that track, Newton leads the ensemble’s background figures and plays a sorrowful open solo that utilizes behind-the-beat quarter note triplets and expressive bent notes. The session opener was Rivera’s “Hank’s Pranks”, a sprightly two-beat melody which gives way to solos in a 4/4 swing groove. D’Amico acquits himself well with a technically adept solo, and Newton contrasts it with a soulful muted turn that takes great liberties with pitch and rhythm. The D’Amico original “Juke Box Judy” finds Newton stretching long ideas over the swift ground beat, while the slow “Gone at Dawn” is a late Newton blues masterpiece. His solo is even sparer than on “The Blues My Baby Gave to Me”, and he only gets a solo introduction and a single 12-bar chorus, but he imbues each note with great feeling and tenderness.

Sly Little Witch from Greenwich (Hank D’Amico) FN solo and out-chorus

Gone at Dawn (Hank D’Amico) FN intro and solo

The final four sessions of Newton’s career were led by singers of varying quality. Miss Rhapsody was the stage name of Viola Wells, and through her career, she performed jazz, blues and gospel under both names. It is possible that she met Newton at Kelly’s Stables, one of her favorite places to sing in New York. Newton gets lots of solo space on her November 21, 1944 session, and there is a lot of shared warmth in the tones of the vocalist and trumpeter. Newton and Wells’ guitarist husband Harold Underhill provide an ongoing obbligato throughout the Benny Carter opus “Blues in My Heart”. The trumpeter is buried behind the vocal and the tenor of Morris Lound during the opening chorus of “Sugar”, but his eight-bar solo is a thing of beauty, with a full rich open tone and a floating melodic line. Newton plays a tender introduction on “Downhearted Blues” and then performs another dual obbligato with Lound behind the vocal (with better balance this time). “Sweet Man” is the highlight of the session with Wells’ earnest vocal inspiring superb solos all around, with Newton sounding more inspired than on any other session of this period. The audio stream below collects Newton’s solos from three alternate takes and the master. What a difference a few minutes makes!

Sweet Man (Miss Rhapsody) composite take with 4 FN solos and obbligatos

The Albinia Jones session of December 22, 1944 was not issued until the late 1970s. One problem with the date was that the singer decided to cover two of Billie Holiday’s most famous blues, “Billie’s Blues” and “Fine and Mellow”. The comparisons to the original recordings do not favor Jones. While Jones’ pitch and diction are very good, her arsenal of expressive devices was severely limited. Newton plays in group obbligatos on “Fine and Mellow” and “What’s the Matter with Me”, and he plays warm solos on “Billie’s Blues” and “Matter”, but the whole session feels like an excuse for the musicians to make a little extra holiday money rather than an effort to make memorable music. A reunion with Big Joe Turner and Pete Johnson from February 2, 1945 is considerably better. Newton’s obbligato and solo on the two-part “S.K. Blues” are confident and strong statements. “Johnson and Turner Blues” underwent a few changes between the two takes. The alternate was recorded first, and in it, Turner sang his choruses up front, closing the record with instrumental solos. Behind Tuner’s vocals, Newton, Don Byas and guitarist Leonard Ware took turns playing dual obbligatos with Johnson. When Turner finished, Newton and Johnson played a chorus together. Newton’s high-register lines overwhelmed Johnson’s improvisation, and the idea was scrapped for the master take. On the master, Turner sings for the first half of the record with the same obbligato roundelay as before. Then Johnson solos alone, Turner returns with Newton in support, followed by a protracted Newton solo and a Turner reprise on the final chorus. Newton tries to cap off the session with a majestic solo on “Watch that Jive” but a couple of missed high notes ruin the effsect. The Stella Brooks session for Asch was recorded May 7, 1946 (15 months after the Turner/Johnson date!) and it followed on the heels of a Town Hall concert where Newton and Brooks performed. Brooks was originally from San Francisco, but had built a cult following in Greenwich Village. Her sound (but not her pitch and delivery) was comparable to Lee Wiley. The band on the date is an all-star affair, featuring Newton, trombonist George Brunies, Sidney Bechet, pianist Joe Sullivan, bassist Jack Lesberg and drummer George Wettling. Considering the array of talent, it’s too bad that Brooks takes up most of the sides with her barely passable renditions of pop songs and blues. Newton’s best moments come on the Harold Arlen standard “As Long as I Live” where he plays a finely-constructed 16-bar variation, an Armstrong-esque blues chorus on “I’m a Little Piece of Leather” and a very brief spot on “Jazz Me Blues”. The rest of the time, he is buried in the group improvisations, which like everything else in this session, is captured in a muddy, low-fi recording.

Johnson and Turner Blues (Pete Johnson/Big Joe Turner) master take

As Long as I Live (Stella Brooks) FN solo

I’m a Little Piece of Leather (Stella Brooks) FN solo

The Stella Brooks session marked Newton’s final appearance on records. The reasons for his second absence from the studios are a little more complex. With only one session per year in 1945 and 1946, it’s conceivable that Newton was not getting enough pay and exposure from recording, and simply stopped looking for record gigs. However, bebop was also a factor. Since the end of World War II, the styles of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk had become the new language of jazz, and any musician who didn’t adapt to the new music was left in the dust. Newton knew all of these men, but he was not a bopper and he had no intention of reinventing himself just to attract an audience. In 1946, the choices were Dixieland and bebop, and Newton chose the former, performing concerts and nightclub engagements with old collaborators like Sid Catlett and Edmond Hall. However, in at least one instance, Newton took interest in a young singer. At his birthday party in 1951, Newton made a private recording with singer Barbara Lea (then known by her birth name, Leacock). The recording has survived but it needs to be restored. Newton’s support of Lea’s talents can be seen in two pieces of correspondence reproduced here. On only one occasion did Newton express regret about his lack of recording opportunities: Wein played Louis Armstrong’s recording of the pop song called “If”. Wein remarked that he thought Armstrong played the melody beautifully; Newton simply shook his head and said “Man, if I had the chance, I could do better.”

Newton continued to split his time between Boston and New York. He continued to teach music to children, played benefits for the Communist magazine “New Times”, and learned a new skill, painting. In the summer of 1948, he was working as a janitor for an apartment building in New York. His apartment in that building caught fire one day, and he lost most of his belongings, including his clothes, horns, mutes and original paintings. A group of fellow musicians raised enough money to get Newton a suit and a horn to play a previously scheduled concert. While Newton got back on his feet after the fire, his drinking increased as his employment decreased. George Wein did what he could to help his old friend, offering gigs at his nightclubs “Le Jazz Douxce” [sic] and Storyville, but eventually Newton’s alcoholism became too much for Wein to handle, and the two friends parted ways.

In 1954, Newton tried to stage a comeback. A group he fronted successfully auditioned for a spot on the television show, “Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts”. However, on March 11, before the band could appear on air, Newton died of acute gastritis. Television might have been a good fit for Newton, as the intensity he projected while playing was very photogenic. With a change in his drinking habits and an apology, he might have been asked to appear at Wein’s first Newport Jazz Festival that summer. And—had he lived long enough—he could have been part of the classic jazz television shows “The Sound of Jazz” (with musical advisor Nat Hentoff) and “Jazz Party” (hosted by longtime New York radio host Art Ford). Sadly, none of those things happened. There was a substantial memorial concert staged in Newton’s memory, but the trumpeter’s scant discography did not lead to posthumous LP reissues. He was soon forgotten, due to his own actions and the short memories of others. However, after all of his personal issues have died away, the music of Frankie Newton still speaks to us with a distinctive and soulful voice, four generations after it was first committed to disc.

Deep and abiding thanks to Dan Morgenstern, George Wein, Loren Schoenberg, Jan Evensmo, Tom Buhmann, Scott Wenzel, Tad Hershorn, Joe Peterson, Vincent Pelote, and Bob Weir.

The audio and video recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.