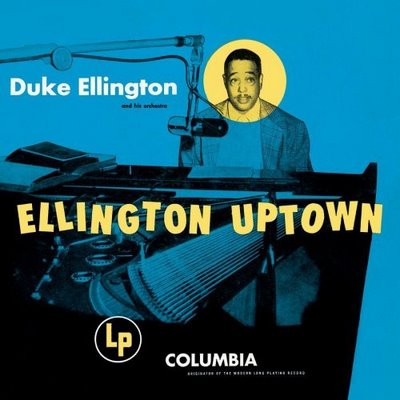

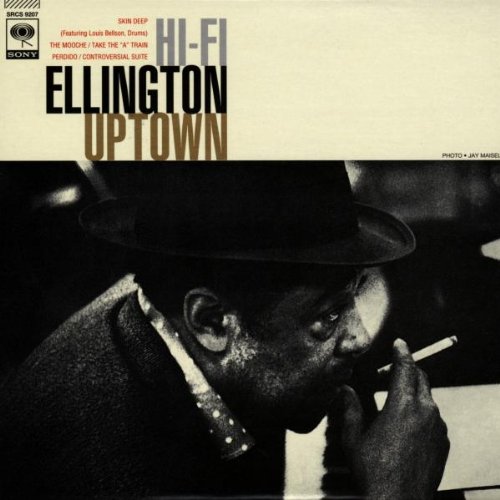

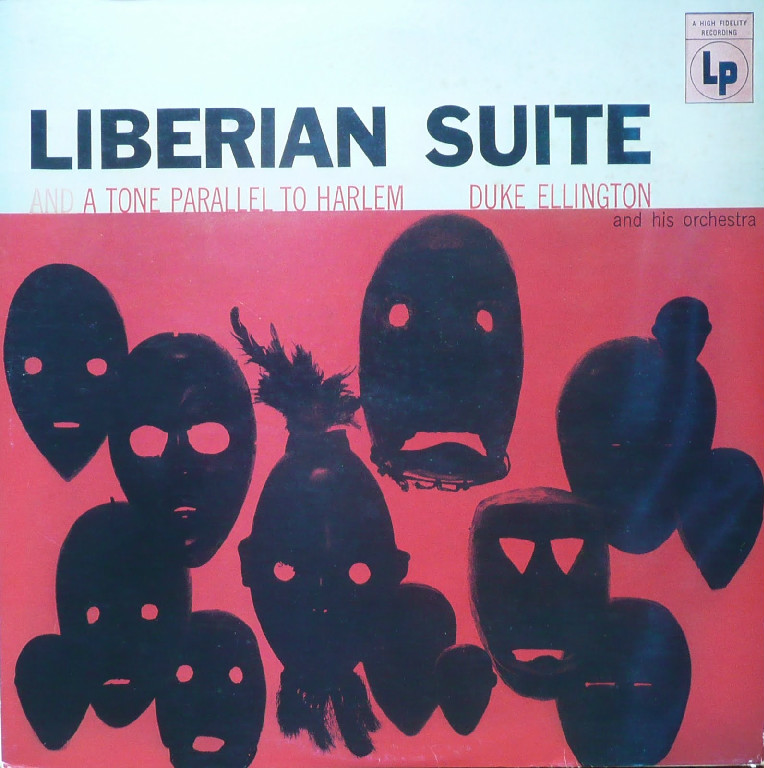

When the Compact Disc was first introduced in the early 1980s, I was an early detractor because the maximum running time was too short to accommodate two full 45-minute LPs. (It still puzzles me why the disc was not engineered to hold 90 to 100 minutes of music—couldn’t that have been accomplished with a 6 inch disc?) However, the extended playing time of the CD allowed for the addition of related recordings. For example, Duke Ellington’s “Ellington Indigos” contained different arrangements on the mono and stereo LP editions, and on both the Stan Getz/J.J. Johnson and Ella Fitzgerald “Opera House” LPs, the mono and stereo LP versions represented different concerts from different cities. The CD reissues of these albums were the first opportunity to collect most or all of the music recorded for those albums. While the mono/stereo issue did not exist in 1951, when Ellington’s “Uptown” LPs were released, the 2004 CD reissue compiles nearly all of the recordings from three different Columbia LP issues of this material. The gray-labeled Columbia Masterworks version, ML 4639, was titled “Ellington Uptown” and contained “Skin Deep”, “The Mooche”, “Take the A Train”, “A Tone Parallel To Harlem” and “Perdido”; the red-labeled version on Columbia CL 830, re-titled “Hi-Fi Ellington Uptown”, inserted “Controversial Suite” in place of “Harlem”, and Columbia CL 848 contained two extended pieces, “Harlem” and “The Liberian Suite”. However, the 90-minute CD of my dreams would have been handy in this case, as this 78-minute CD omits alternate takes of “I Like the Sunrise” and substitutes a previously unissued version of “Dance No. 5” from “Liberian Suite” for the originally issued version.

When the Compact Disc was first introduced in the early 1980s, I was an early detractor because the maximum running time was too short to accommodate two full 45-minute LPs. (It still puzzles me why the disc was not engineered to hold 90 to 100 minutes of music—couldn’t that have been accomplished with a 6 inch disc?) However, the extended playing time of the CD allowed for the addition of related recordings. For example, Duke Ellington’s “Ellington Indigos” contained different arrangements on the mono and stereo LP editions, and on both the Stan Getz/J.J. Johnson and Ella Fitzgerald “Opera House” LPs, the mono and stereo LP versions represented different concerts from different cities. The CD reissues of these albums were the first opportunity to collect most or all of the music recorded for those albums. While the mono/stereo issue did not exist in 1951, when Ellington’s “Uptown” LPs were released, the 2004 CD reissue compiles nearly all of the recordings from three different Columbia LP issues of this material. The gray-labeled Columbia Masterworks version, ML 4639, was titled “Ellington Uptown” and contained “Skin Deep”, “The Mooche”, “Take the A Train”, “A Tone Parallel To Harlem” and “Perdido”; the red-labeled version on Columbia CL 830, re-titled “Hi-Fi Ellington Uptown”, inserted “Controversial Suite” in place of “Harlem”, and Columbia CL 848 contained two extended pieces, “Harlem” and “The Liberian Suite”. However, the 90-minute CD of my dreams would have been handy in this case, as this 78-minute CD omits alternate takes of “I Like the Sunrise” and substitutes a previously unissued version of “Dance No. 5” from “Liberian Suite” for the originally issued version.

Both versions of the original album (ML 4639 and CL 830) captured Ellington during a crucial transition for his orchestra. Three long-standing stars of the band, alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, trombonist Lawrence Brown and drummer Sonny Greer, left the group, and in order to maintain his busy schedule of touring and recording, Ellington had to find replacements quick. Because his music was written for specific instrumentalists, Ellington also had to re-write his music to fit his new musicians. The “Uptown” album allowed him to showcase those replacements, Willie Smith (and his eventual replacement, Hilton Jefferson), Britt Woodman and Louis Bellson. CL 848 finds Ellington in a different type of transition, as he explores ways to write for the new LP record. “A Tone Parallel to Harlem” was one option: a long, extended piece in a single movement. “Liberian Suite” was the other option. It contained the song “I Like the Sunrise” and a series of five dances. Thus, it represented the suites that Ellington would eventually create for his future albums. Because “Liberian Suite” dated from late 1947 and “A Tone Parallel to Harlem” was recorded in 1951, CL 848 also offered its listeners the chance to compare the sound of the band with Hodges, Brown and Greer, to the then-current version with Smith, Woodman and Bellson.

The Masterworks version was the first and strongest edition of the album. “Skin Deep” remains one of the greatest drum features ever written for big band. The melody is well-crafted and the arrangement offers several challenging passages to the horns. While the drum solo is the primary focus of the composition, the contrasting episodes allow the band to have its time in the spotlight. Bellson was one of the most creative drummers in jazz history, with seemingly endless energy and excellent musical taste to go with it. His double bass drums were his trademark and they are featured towards the end of his solo, but Bellson treats them as an addition to his percussion arsenal, not a gimmick in their own right. “The Mooche” was originally written in 1928, but the present version features immaculate section work, and an imaginative clarinet duet with Russell Procope in the foreground and Jimmy Hamilton in the echo chamber. There are also excellent solo spots for trumpeter Ray Nance, trombonist Quentin Jackson, Hilton Jefferson and baritone saxophonist Harry Carney. The remake of “Take The A Train” is in three tempos, opening with a medium-fast section featuring Ellington’s piano and the cute singing and scatting of Betty Roché, before moving to a slow rendition for the tenor sax of Paul Gonsalves, and concluding Gonsalves’ solo in a blazing fast tempo. Gonsalves’ surging tenor shows why he was such an asset to the Ellington band.

The Masterworks version was the first and strongest edition of the album. “Skin Deep” remains one of the greatest drum features ever written for big band. The melody is well-crafted and the arrangement offers several challenging passages to the horns. While the drum solo is the primary focus of the composition, the contrasting episodes allow the band to have its time in the spotlight. Bellson was one of the most creative drummers in jazz history, with seemingly endless energy and excellent musical taste to go with it. His double bass drums were his trademark and they are featured towards the end of his solo, but Bellson treats them as an addition to his percussion arsenal, not a gimmick in their own right. “The Mooche” was originally written in 1928, but the present version features immaculate section work, and an imaginative clarinet duet with Russell Procope in the foreground and Jimmy Hamilton in the echo chamber. There are also excellent solo spots for trumpeter Ray Nance, trombonist Quentin Jackson, Hilton Jefferson and baritone saxophonist Harry Carney. The remake of “Take The A Train” is in three tempos, opening with a medium-fast section featuring Ellington’s piano and the cute singing and scatting of Betty Roché, before moving to a slow rendition for the tenor sax of Paul Gonsalves, and concluding Gonsalves’ solo in a blazing fast tempo. Gonsalves’ surging tenor shows why he was such an asset to the Ellington band.

With its title, subject matter and extended length of nearly 14 minutes, “A Tone Parallel to Harlem” is a spiritual offspring of Ellington’s 1943 masterpiece “Black, Brown & Beige”. Ellington had been burned by negative critical reaction to the earlier work, but this work received a much better response and remained in the Ellington tour repertoire for several years. Nance opens the composition by pronouncing the word “Harlem” on his plunger-muted trumpet, and as Ellington’s musical travelogue winds its way through upper Manhattan, several band members have short cameo solos that offer both individual expression and integral parts of the composition. While the individual melodies of the composition are not particularly memorable, the overall work holds together much better than the extended arrangements of “Mood Indigo”, “Sophisticated Lady” and “Solitude” that Ellington created in the previous year for his Columbia LP, “Masterpieces by Ellington”. For my money, Ellington’s best recorded version of “Perdido” was the 1960 version co-arranged by Gerald Wilson, Clark Terry and Jimmy Hamilton. However, the “Uptown” rendition has much to recommend it, including a boogie style piano solo by Billy Strayhorn, Hamilton’s bop line on the changes, a superbly-played chorus by the trombones, and a brass chase with Cat Anderson, Ray Nance, Clark Terry, Willie Cook and Britt Woodman.

“The Controversial Suite” is an odd little piece of Ellingtonia, with its two movements poking fun at the Dixie revival and Stan Kenton. While the band’s performance of the work is at its usual high standard, the whole composition seems rather pointless these days. Ellington was usually very diplomatic about fellow musicians and other musical styles, so this little piece of musical satire is really beneath him. He came up with a better solution in later years: he would proclaim to his audiences that he had found the next new movement in jazz, and then they would be treated to an expert impression of Louis Armstrong! “Liberian Suite” never appeared on the “Uptown” LPs, but its presence is most welcome on this CD. “I Like the Sunrise” features one of Al Hibbler’s most expressive vocals, and the series of dances—mysteriously left unnamed by Ellington—offer a wide range of styles and soloists, including Nance on violin, Al Sears on tenor, Jimmy Hamilton on clarinet and Tyree Glenn on vibes. Ellington’s score contains several memorable melodies and several beautifully-scored sections that evoke African dance.

A newcomer to Ellington can start with just about any Ellington record and be assured of hearing quality music played with stunning precision. Yet, considering that the late 40s and early 50s were a difficult time for the band business in general (and Ellington in particular), it is enlightening to hear such exuberant performances by the Ellington band. It has been long noted that Ellington could bring out the best in his musicians, but “Ellington Uptown” shows him succeeding in a most profound way.