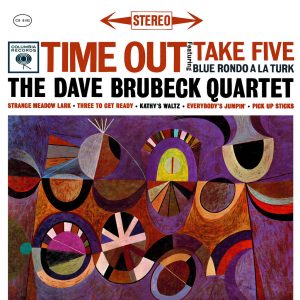

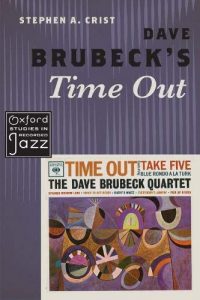

On the afternoon of June 25, 1959, the Dave Brubeck Quartet entered Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studios to record a pioneering album of jazz played in what was then known as “odd meters” (3/4, 9/8, 5/4 and 6/4). Over the course of production, the album title changed from the awkward “Out of Our Time” to the pithy “Time Out”, but the concept of moving jazz away from 4/4 time had long been one of Brubeck’s obsessions. Growing up on his father’s ranch in California, Brubeck was fascinated by the cross-rhythms he sensed from the motion of the farm equipment. He learned how to compose in mixed meters while in college and in studies with Darius Milhaud, and began recording his earliest time experiments with his Octet and Trio in the late 1940s and early 1950s. As the 1950s progressed, Brubeck continued to combine and mix time signatures in recordings with his enormously popular Quartet. In a new monograph from the “Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz”, author Stephen A. Crist examines the history and legacy of “Time Out”, using rare materials from the Brubeck Collection at the University of Pacific to illustrate and enlighten his points.

On the afternoon of June 25, 1959, the Dave Brubeck Quartet entered Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studios to record a pioneering album of jazz played in what was then known as “odd meters” (3/4, 9/8, 5/4 and 6/4). Over the course of production, the album title changed from the awkward “Out of Our Time” to the pithy “Time Out”, but the concept of moving jazz away from 4/4 time had long been one of Brubeck’s obsessions. Growing up on his father’s ranch in California, Brubeck was fascinated by the cross-rhythms he sensed from the motion of the farm equipment. He learned how to compose in mixed meters while in college and in studies with Darius Milhaud, and began recording his earliest time experiments with his Octet and Trio in the late 1940s and early 1950s. As the 1950s progressed, Brubeck continued to combine and mix time signatures in recordings with his enormously popular Quartet. In a new monograph from the “Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz”, author Stephen A. Crist examines the history and legacy of “Time Out”, using rare materials from the Brubeck Collection at the University of Pacific to illustrate and enlighten his points.

Crist’s narrative expands far beyond the album’s fairly quick production (which consisted of 4 recording sessions in the summer, with LP release at the end of 1959). He starts with Brubeck’s boyhood recollection of the ranch machinery, follows Brubeck’s rise to fame and development as a composer, examines every “Time Out” composition in great detail, includes discussions of Brubeck’s re-recordings of the “Time Out” tracks, and examines his later compositions with non-traditional time signatures. The book features several reproductions of Brubeck’s rejected manuscripts, and Crist’s precise descriptions of the illustrations allows readers to follow Brubeck’s thought process as he works his way through various problems. Crist also traces the evolution of compositions, showing how “Pick Up Sticks” was a natural extension of Joe Morello’s previously recorded drum feature “Watusi Drums”, and how “Everybody’s Jumpin’” became—as “Everybody’s Comin’”—part of Brubeck’s projected Broadway show, “The Real Ambassadors”.

“The Real Ambassadors” never made it to Broadway, but much of the show’s development occurred as “Time Out” was being recorded and prepared for release. Crist argues that Brubeck spent more time working on “Ambassadors” more than “Time Out” in the latter half of 1959; in the end, Crist proves that the two projects had a lot more in common than the song “Everybody’s Jumpin’/Comin’”. “Ambassadors” examines the dichotomy of black jazz musicians who traveled in first-class as overseas representatives of the US State Department, but were treated as second-class citizens when playing in their home country. Brubeck knew of this issue first-hand. A March 1959 Quartet performance at the University of Georgia was suddenly cancelled when the school organizers discovered that Brubeck had a black bassist, Eugene Wright. Racially-mixed performances were against the Jim Crow laws of the time, and Brubeck, a longtime supporter of civil rights, refused to replace Wright with a white musician. The cancellation caused a furor in the press, including a searing commentary from Ralph J. Gleason ridiculing the school and the organizers. Incidents like this only strengthened Brubeck’s resolve. He and his lyricist wife, Iola had been working on “Ambassadors” since 1956, but the work took shape during 1959, and Crist notes that the show’s finale “Swing Bells” includes a section based on the theme of “Watusi Drums”.

“The Real Ambassadors” never made it to Broadway, but much of the show’s development occurred as “Time Out” was being recorded and prepared for release. Crist argues that Brubeck spent more time working on “Ambassadors” more than “Time Out” in the latter half of 1959; in the end, Crist proves that the two projects had a lot more in common than the song “Everybody’s Jumpin’/Comin’”. “Ambassadors” examines the dichotomy of black jazz musicians who traveled in first-class as overseas representatives of the US State Department, but were treated as second-class citizens when playing in their home country. Brubeck knew of this issue first-hand. A March 1959 Quartet performance at the University of Georgia was suddenly cancelled when the school organizers discovered that Brubeck had a black bassist, Eugene Wright. Racially-mixed performances were against the Jim Crow laws of the time, and Brubeck, a longtime supporter of civil rights, refused to replace Wright with a white musician. The cancellation caused a furor in the press, including a searing commentary from Ralph J. Gleason ridiculing the school and the organizers. Incidents like this only strengthened Brubeck’s resolve. He and his lyricist wife, Iola had been working on “Ambassadors” since 1956, but the work took shape during 1959, and Crist notes that the show’s finale “Swing Bells” includes a section based on the theme of “Watusi Drums”.

The Brubeck Quartet made a four-month tour of Europe and the Middle East in 1958, and the interaction of the quartet with a group of local musicians in Turkey inspired the opening track on “Time Out,” “Blue Rondo a la Turk”. With its catchy theme brilliantly presented in a reconfigured 9/8 time scheme (counted in rapid metric groupings of 2 + 2 + 2 + 3 in addition to the normal 3 + 3 + 3), “Blue Rondo” announced that “Time Out” was to be a no-holds-barred examination of heretofore unexplored time signatures. Brubeck’s implementation of the classical rondo form allowed him to contrast related melodic motives, and the outstanding blues choruses by Paul Desmond and Brubeck united the worlds of Middle Eastern and American music. Crist’s musicological analysis of “Blue Rondo” is quite precise in terms of the composition, but he seems to miss how the blues improvisations contribute to the overall success of the track. For example, the now-famous black chord sequence which Brubeck improvised on this track is not only the logical climax of the blues section; it also allows an American-bred musical form to stand at the same emotional level as the Turkish folk form. “Blue Rondo” needed this equalizing force to maintain its artistic balance.

Of course, the most successful track on “Time Out” was Paul Desmond’s “Take Five”. Desmond used to quip that the song was inspired by the rhythm of a slot  machine in Reno. Crist knocks down that story with ease, opting instead for the likely scenario that Desmond brought in a pair of unrelated phrases, and that Brubeck and Morello helped to form the piece into a composition. The piece gave the group endless problems in the studio. Crist, using Brubeck’s copies of the original session reels, gives us a take-by-take rundown of the numerous false starts and breakdowns of this signature track. While all four members of the quartet eventually became comfortable with the concept of playing and improvising in 5/4 time, here they struggled to create a take without dropped beats and other mistakes. Crist’s descriptions of these unissued takes are sufficiently vivid to inform readers of their feel and quality; frankly, it may be best for all concerned for these items to remain in the vault.

machine in Reno. Crist knocks down that story with ease, opting instead for the likely scenario that Desmond brought in a pair of unrelated phrases, and that Brubeck and Morello helped to form the piece into a composition. The piece gave the group endless problems in the studio. Crist, using Brubeck’s copies of the original session reels, gives us a take-by-take rundown of the numerous false starts and breakdowns of this signature track. While all four members of the quartet eventually became comfortable with the concept of playing and improvising in 5/4 time, here they struggled to create a take without dropped beats and other mistakes. Crist’s descriptions of these unissued takes are sufficiently vivid to inform readers of their feel and quality; frankly, it may be best for all concerned for these items to remain in the vault.

Crist also offers several other surprises. For example, the master take of “Strange Meadow Lark”—the only piece on “Time Out” entirely in 4/4—was constructed from several takes (and even after Crist points out the location of the splices, it’s very difficult to discern them!) Crist also examines several drafts of Iola’s lyric for the song before discussing Carmen McRae’s famous recording. Speaking of lyrics, the various words to “Take Five” and “Blue Rondo” are transcribed in full, including a stunning French version of the latter work, as recorded by Claude Nougaro. In addition to clearing up the typographical error on “Kathy’s Waltz”—written for Brubeck’s daughter, Catherine—Crist presents excerpts from an interview with Cathy herself, and he also produces the photograph which inspired the composition, featuring the 5-year-old Cathy dancing to the music of her older brothers.

Brubeck frequently related the story that the businessmen at Columbia were against the release of “Time Out”, feeling it would be a commercial flop. Fortunately, Brubeck had an important supporter in Columbia’s president, Goddard Lieberson. When the album was released and sales went through the roof, Brubeck was accused of going commercial! In reality, he proved that artistic excellence and financial success were not mutually exclusive. We can be grateful that this album exists due to the perspicacity of its creators and supporters. Stephen Crist enhances the album with his fine writing and astounding research. Reading this book will make you want to listen to the album again, and when you do, you’ll probably discover that it is every bit as thrilling as it was on your first listening.