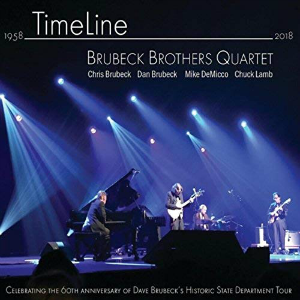

The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s 1958 State Department tour of Europe and the Middle East was the subject of both the Brubeck Brothers’ new CD, “Timeline” (Blue Forest 18-03001) and a recent PBS/BBC documentary, “The Jazz Ambassadors”. Ironically, Dave’s son, Chris Brubeck, was unable to see the documentary because he was doing a West Coast concert tour to promote the album. Still, the release of the album, and the 60th anniversary of the tour provided a great opportunity for Chris to chat with Jazz History Online’s Thomas Cunniffe.

“Timeline” (Blue Forest 18-03001) and a recent PBS/BBC documentary, “The Jazz Ambassadors”. Ironically, Dave’s son, Chris Brubeck, was unable to see the documentary because he was doing a West Coast concert tour to promote the album. Still, the release of the album, and the 60th anniversary of the tour provided a great opportunity for Chris to chat with Jazz History Online’s Thomas Cunniffe.

Thomas Cunniffe: The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s tour for the State Department was a resounding success, in both artistic and political terms. In fact, the opportunities for concerts kept coming, even after the trip started! When the Quartet left the US, how long did they expect to be gone?

Chris Brubeck: When they left, the plan was that they would be away for three months. By the time the tour actually ended, it was closer to four months. The first place they played was in England. They hadn’t played there before, and they got a greater reception that they expected. I think he was shocked that so many people wanted to hear this hot new group from the West Coast. There was a jazz writer over there named Steve Race, and he had knocked the group’s recordings in the years before, but he wrote a big “mea culpa” later, writing that he had heard the band live and that his earlier perception was wrong.

TC: I understand that the quartet had a big personnel change right before the trip.

CB: It was Gene Wright’s first tour with the band. While it wasn’t like traveling in the American South, there were a few people who said “Hey, you didn’t tell us you were bringing in a black bassist”. There may have been some talk like “Wouldn’t it be easier if you brought a different bass player?” But Gene was willing to come on this trip. He had the kind of personality that he could deal with it, and Dave agreed that he could.

TC: Those State Department tours were quite grueling. Velma Middleton died in the middle of Louis Armstrong’s tour, Dizzy Gillespie’s band was sent to play a concert in the midst of an anti-American rally in Greece, and Ray Nance quit the Duke Ellington band during their Middle East tour after a falling out with his roommate Cootie Williams. And despite all of the vaccinations the artists endured before leaving the States, someone always got sick on the road.

CB: A lot of people got dysen tery. Somewhere in India, they had to leave Paul Desmond behind so he could recuperate at a hospital. And he begged them, “Don’t leave me here! Come back and rescue me!” Paul liked to drink, and I’ll bet he used ice cubes. The ice cubes can get you if you’ve got funky water.

tery. Somewhere in India, they had to leave Paul Desmond behind so he could recuperate at a hospital. And he begged them, “Don’t leave me here! Come back and rescue me!” Paul liked to drink, and I’ll bet he used ice cubes. The ice cubes can get you if you’ve got funky water.

TC: There were several crazy things that happened to the Brubeck Quartet over there. I read about a hotel in Baghdad that was attacked hours after the Quartet departed. Did your dad tell you any other wild stories?

CB: Actually, my dad told me a lot of stories about that trip. In Afghanistan, he met a man with a nickname like “The Liberator of Kabul” or something like that. The story was that he had gotten some occupying force in Kabul to leave because they thought there was a huge army coming down from the mountains. Actually, the guy had gathered a bunch of goats and mules, put candles on their backs, and walked them around at night, which made the occupying force think that the lights were a bunch of soldiers that were marching on the city! That was a fresh story for my dad, so I think it happened right around the time they were there.

TC: Chris, I know that you and your brother Dan were considered too young to go on the tour, but your brothers Darius and Michael went along, as did your mother, Iola. One of the most famous stories about the trip was about how Dave had to go to East Germany to get papers to allow the family to go behind the Iron Curtain.

CB: Dave had to travel to East Berlin in order to get the papers that would allow my mother and my two older brothers to travel into Poland. But the only way to get those papers was to go to a place where you weren’t allowed to be. He certainly didn’t want my mom to take the risk, and believe it or not, my dad was a nervous kind of guy. Someone like Gerry Mulligan could have just nonchalantly breezed in there and got it done, but not my dad. The German citizen who drove him over there suggested that Dave get in the trunk, but Dave said, “No, no, no! If they stop us and I’m in the trunk, I’ll look super-guilty, whereas if I’m in the back seat, it could be explained as a misunderstanding.” I think they had to go through Checkpoint Charlie.

TC: I don’t think Checkpoint Charlie was there yet, because the Berlin Wall had not been built yet. However, I read that they went through the Brandenburg Gate, and the experience inspired Dave’s composition of the same name.

CB: Oh, yeah. That’s what inspired the piece! It’s such a beautiful piece. I’m surprised it wasn’t a more dissonant musical exercise!

TC: Another story, which Darius related in the PBS documentary, was about the first performance of Dave’s original, “Dziekuje”, which was dedicated to the Polish people. Apparently, when Dave finished playing the piece, the crowd sat in silence for awhile before giving a tremendous ovation.

was dedicated to the Polish people. Apparently, when Dave finished playing the piece, the crowd sat in silence for awhile before giving a tremendous ovation.

CB: There’s an interesting codicil to that story. About 5 years ago, my brother Darius had a gig in Poland. My brother Dan and I were already over there, so we decided to play the concert together. We went to a jazz festival located about three hours away from Warsaw. Darius said, “You know, we ought to play that tune”. We’d never played it as a group, but I knew it from playing it with Dave. We did the song as a tribute, and after the concert, I met several gentlemen in wheelchairs with tears streaming down their faces who said they were at the exact concert when Dave first played that song. They also said, “You have no idea how meaningful that song is to the Polish people.”

TC: European audiences have always appreciated jazz more than Americans. Can you offer any theories why?

CB: Audiences that aren’t American value something about jazz more than Americans do. When I played a festival in Nice, I could tell that the French people really loved jazz. I asked a French fan why, and he said that our music reminded them of the Americans who liberated France from the Nazis in 1944. In contrast, I also played concerts with Dave in Germany. We always had very good receptions there, and when I asked a German fan, he said “Our fathers were in Hitler’s army, and our generation hates our parents for allowing the Third Reich to happen. And so when we go to a jazz concert, it’s a bridge of peace and understanding in this big generational gap.” I never thought of that angle. My dad was in World War II, and it certainly makes sense that any contemporary German guy was involved one way or the other, either serving in the army, or being shot for not serving.

TC: Getting back to the 1958 tour, we have no recordings of the group after they left Berlin, and that’s when this trip really got interesting! Dave composed a lot of music based on his experiences in the Middle East.

TC: Getting back to the 1958 tour, we have no recordings of the group after they left Berlin, and that’s when this trip really got interesting! Dave composed a lot of music based on his experiences in the Middle East.

CB: He was really impressed with the interaction with the Indian musicians. For the first time in his life, he realized the parallels between a life of studying Indian music and jazz. The Indian drummers used to love to hang out with Joe Morello, because his ears were so great. He could trade phrases with those drummers. Years later, my brother Dan was in India. He went to a music store to buy something and he paid for it with his credit card. When the owner saw the last name Brubeck, he said that his uncle was one of the drummers at one of those jam sessions. Then, he went to the back of the store and pulled out a large scrapbook with pictures of Dave. He insisted that Dan attend a concert that night by a local group. The ragas they played had lots of mixed meter and the form was something like 38 bars. Even as a drummer, Dan had a hard time keeping track of the form, but the audience was right with them. Every time the form came back to the top, everyone clapped on the first beat! Over here, we’re lucky if we can get a bunch of white people to clap on two and four!

TC: Of course, the most famous piece to come from the trip was “Blue Rondo a la Turk”.

CB: One of Dave’s teachers, Darius Milhaud, made a specific point that a composer’s obligation is to listen to music from all over the world and borrow from it while marinating it with his own ideas. In Milhaud’s case, he spent time in South America and in Harlem. Of course, the music in Harlem was where he got the inspiration for “La Création du Monde”, which incorporates the jazz of that era. It actually pre-dates Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue”. It wasn’t that Gershwin stole from Milhaud; if you’re listening (and you’re not tone-deaf) you’re going to hear blues scales in Harlem. Dave was very conscious of Milhaud’s lesson, and he always kept his ears open. That’s what led him to combine the Turkish street rhythm with a classical rondo form and the blues. In the later years of his life, Dave said that he thought he might have started the world music genre with “Blue Rondo”.

TC: He was right! It’s both Third Stream and World music. You and Dan made a very interesting change to the piece when you recorded it for your new album, “Timeline”.

for your new album, “Timeline”.

CB: We recorded that track at the end of the session. Everyone was very tired, and I was so sick that I was lying on the floor while I played my electric bass. I suggested “Blue Rondo” because it was the most significant piece that came out of that trip. Then I told them that I wanted to add a few extra bars of 9/8 and they looked at me with their bleary eyes as if I was crazy. We’d been playing the song in the traditional way for years and they weren’t enthusiastic about changing it. There was a take or two where we forgot to add the extra bars, so I had to prop myself up and nod my head to remind the band of the changes. One thing I like about the final take is that the blues section is very relaxed. Everyone was so tired that there was no other way to be! A few days later, I asked Dan to add hand drums to the piece, and I love the energy it brought to the piece.

TC: Among the other tracks is “Tritonis”, a tune not associated with the 1958 tour, but performed by you and your dad in Russia 30 years later. I love your new version. It’s much more tranquil than when you played it with Dave.

CB: I’m glad you liked it! I’ve heard some recordings where it had that kind of aquatic feel. When I played it with Dave, he always attacked it so frantically. For the new recording, we thought it might be interesting to stay in that Debussy-ish groove. I’m really knocked out by Dan’s brush solo. It’s so melodic, harmonic and musical. Obviously, the song is a little off the 1958 timeline, but Dan really wanted to include it on this album.

TC: On “Easy as You Go”, a song originally from “The Real Ambassadors”, you overdubbed the lead line on bass trombone. Chuck Lamb’s piano accompaniment seemed particularly in sync with your trombone part. Did you overdub those parts at the same time, or did one come before the other?

I’m pretty sure that we recorded the rhythm tracks first. Chuck did a great job of imagining me in it. When I overdubbed the bass trombone part, I was able to respond to what Chuck had laid down before. Chuck can be a very hard-driving player, but I think this record captures his softer side.

TC: I’ve had the good fortune to perform some of your dad’s classical works. Are there new performances of these pieces planned anytime soon?

CB: With Dave’s centennial coming up in 2020, we want to encourage choirs and orchestras all over the world to help celebrate by performing his music.

TC: I’ll gladly second that wish! Thanks for speaking with me today.

CB: My pleasure.