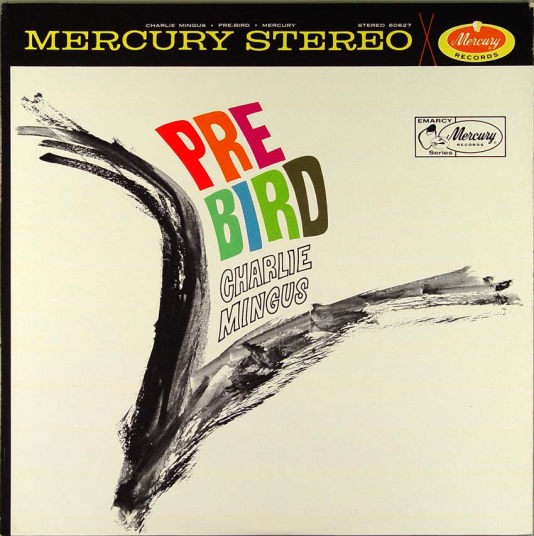

Charles Mingus was ready for the world but unfortunately the world wasn’t ready for Mingus. Recorded in 1960, “Pre-Bird” (later reissued as “Mingus Revisited”) is a set that Charles Mingus devoted to his astonishingly pre-bop compositions. Although many of his later works were deeply affected by Charlie Parker, this particular recording demonstrates the strong influences of Duke Ellington and the blues. It features six unconventional originals and two arrangements of songs from the Ellington canon. Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train” (with an interpolation of its harmonic cousin, “Exactly Like You”) and “Do Nothin’ Til You Hear From Me” (paired with “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart”) are both taken at screaming, smoking, and swinging Mingus tempos and feature soloists Joe Farrell, Jimmy Knepper, Booker Ervin, and Yusef Lateef.

Charles Mingus was ready for the world but unfortunately the world wasn’t ready for Mingus. Recorded in 1960, “Pre-Bird” (later reissued as “Mingus Revisited”) is a set that Charles Mingus devoted to his astonishingly pre-bop compositions. Although many of his later works were deeply affected by Charlie Parker, this particular recording demonstrates the strong influences of Duke Ellington and the blues. It features six unconventional originals and two arrangements of songs from the Ellington canon. Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train” (with an interpolation of its harmonic cousin, “Exactly Like You”) and “Do Nothin’ Til You Hear From Me” (paired with “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart”) are both taken at screaming, smoking, and swinging Mingus tempos and feature soloists Joe Farrell, Jimmy Knepper, Booker Ervin, and Yusef Lateef.

In “Prayer for Passive Resistance,” Mingus’ bass introduction leads us to a church meeting with Lateef’s tenor preaching soulfully to the congregation amidst a sudden 12/8 groove that seems to come out of nowhere. Mingus personifies the epitome of what jazz is all about. His music tells colorful stories with honest expressions, never contrived and always full of surprises. He is not afraid to go into unexplored territory whether it is through risky rhythmic diversions or dissonant contrasting lines.

I was most intrigued with “Eclipse” and “Weird Nightmare” as I have sung and recorded both songs (along with writing published lyrics to three other Mingus compositions). Mingus had the heart of a poet and his words are poignant and rich with imagery. In “Eclipse” he metaphorically uses the sun and moon to describe interracial love and the public resistance he and others experienced during this time period. Some look through smoked glasses hiding their eyes, others think it’s tragic sneering as dark meets light. But the sun doesn’t care and the moon has no fear for destiny’s making her choice. Although it is said that he wrote the song for Billie Holiday, Sheila Jordan told me that Mingus approached her to sing the first version of this song because of her interracial marriage with Duke Jordan.

Lorraine Cusson sings a sensuous, breathy rendition demonstrating an astute ear through difficult melodic and harmonic passages. Cusson also sings “Weird Nightmare,” another highly challenging vocal piece with the bass required to play all twelve notes of the chromatic scale winding through a multitude of chord changes in a standard AABA form. During the recording session Cusson accidentally reversed the order of the last line, changing it from Bring me a love with a heart of gold, to Bring me a heart with a love of gold. She assumed Mingus wasn’t upset enough to gamble another cut. Both of these songs should become part of the vocal jazz repertoire.

“Mingus Fingus #2” follows the basic big band format with a slight nod towards bop and edging towards the familiar Mingus musical detours. Mingus originally recorded this on November 10, 1947, as a member of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. On “Bemoanable Lady” the great Eric Dolphy is showcased opening with a sultry alto saxophone wail backed up with tonal complexities from the rest of the orchestra reminiscent of the Ellington compositional sound but tweaked enough to maintain the Mingus signature.

The final composition, “Half-Mast Inhibition” features the entire 22–piece ensemble with tuba, cello, woodwind and percussion conducted by Gunther Schuller. This was one of my favorite tracks based on my affection for the mixture of classical and jazz components. Often-considered one of Mingus’ masterpieces, this extended piece of over eight minutes is a scenic journey beginning with the beautiful cello work of Charles McCracken, a tuba interlude featuring Don Butterfield, and vibrant waltz movements that all intensely build up to a wild brass explosion, eventually fading into a dynamic serenity. According to the liner notes, Mingus, 19 at the time, was suicidal when he wrote the piece. He said, “I learned through meditation the will to control, and actually feel calmness. I found a thing that made me think I could die if I wanted to. And I used to work at it. Not death and destruction, but just to will yourself to death. While I was laying there, I got to such a point that it scared me and I decided I wasn’t ready.” An eerie allusion to “Jingle Bells” symbolizes the vision that made him want to live.

The genius of Mingus lies not only in his technical organization but also in his collaboration of musical genres with vast expressions of emotional moods, impressions, and feelings. When “Pre-Bird” was issued in 1960, it was considered as cutting-edge progressive jazz. Even today his music continues to stretch boundaries, fascinating musicians and listeners. “Pre-Bird” should be in the recording collection of every serious Mingus fan.